In the wake of an alleged uptick in the rate of bus and subway fare evasion and concerns over assaults on transit operators, New York Governor Cuomo and New York City Mayor de Blasio recently agreed to assign 500 additional uniformed officers to the New York City Transit system. The rationale behind this decision is to “improve rider safety, protect transit workers, and deter fare evasion.”

Ensuring safe conditions for transit workers and riders is crucial. But many riders won’t feel safer with a heightened police presence if it exacerbates the over-policing of subway stations in communities of color. It could also increase the number of arrests for fare evasion, reversing promising declines over the past two years.

Adopting more aggressive enforcement strategies may also cast a pall over what should be a major service upgrade for riders. All-door boarding is slated to roll out across the whole MTA bus system in 2021, which should improve speed and reliability. Without fare checks at the front door, all-door boarding relies on occasional fare inspections. If the MTA and NYPD don’t address bias and excessive force in fare enforcement, these problems may become more widespread in the bus system.

Today, public information about who is arrested and receives summonses in the NYC subway system remains limited. Based on quarterly data released by the NYPD, we do know that NYPD disproportionately issues criminal summonses for fare evasion to young men of color. People of color are more likely to be arrested than whites, and men are more likely to be arrested than women.

We don’t know how these numbers compare to the demographics of who commits fare evasion – while the MTA says it keeps records, such information has never been made public. But analysis from the Marshall Project and the Community Service Society of New York reveals that police precincts with higher turnstile arrest rates do not correlate with higher rates of ridership or criminal activity; rather, the data suggests police focus on largely black and Hispanic areas.

The way NYPD releases data also limits analysis. The NYPD is required by city law to publicly report data on race, sex, and age for fare arrests and summonses at every subway station. However, it currently reports the full demographic data of arrestees in only 10 of the system’s 472 stations, listing only percentage breakdowns for 90 other stations. These percentages fail to clearly convey the scale and location of NYPD fare enforcement activity.

NYPD contends that releasing the enforcement data of every station could aid terrorists by revealing which stations have relatively low police presence. However, Council Member Rory Lancman, who sued the NYPD for the full data set, argues that previous arrests and summonses don’t necessarily reflect future police deployments, as safety and fare evasion enforcement priorities shift over time.

More comprehensive data about the extent of fare evasion could well lead transit leaders in a different direction than a $40 million deployment of armed police.

In 2009, San Francisco’s transit agency, SFMTA, conducted a fare payment survey of “41,239 customers on 1,141 vehicle runs,” which “provided enough samples by time period, route and vehicle occupancy to identify fare payment patterns at a disaggregated level.”

Leaders at SFMTA had initiated the survey because of concerns about lost revenue due to fare evasion. But the inquiry revealed that the fare evasion rate was actually lower than internal predictions, which generated leverage to institute more rider-friendly policies like citywide all-door boarding.

In New York, the MTA has not publicly released fare payment surveys of similar scale and rigor. Lacking that information — as well as any credible demonstration that NYPD conducts fare enforcement without bias — the public has little reason to trust that additional police deployment in the subways will address real problems.

What is clear is that criminal arrests for fare evasion are a severe penalty for an infraction on par with failure to pay a parking meter, and that local government and law enforcement have much more work to do to create an un-biased, less punitive fare enforcement system.

District attorneys across the city should follow the lead of Manhattan DA Cy Vance and decline to prosecute fare evasion cases, which frees up the courts for more pressing issues, and doesn’t burden fare evaders with a criminal record.

Police should be required to demonstrate a deployment strategy without racial bias. Officers should also be better trained in de-escalation strategies. There’s no reason that a stop for fare evasion should end in situations like this.

In San Francisco, SFMTA’s proof of payment officers are unarmed, and will soon be trained in de-escalation and anti-bias strategies in order to prevent violent situations. In Portland, OR, TriMet’s fare enforcement officers can use interactions over an unpaid fare as an opportunity to let riders know about the agency’s low-income fare program. TriMet also offers riders alternatives to paying fare evasion fines, such as completing community service.

The de Blasio administration has yet to scale up its Fair Fares program for half-price MetroCards, with open enrollment set to begin in 2020. It would only add a dose of cruelty to mount more aggressive fare enforcement before people with low incomes have the chance to avail themselves of these reduced barriers to farecards.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More Winning Free Fares for Youth in New Orleans

Winning Free Fares for Youth in New Orleans

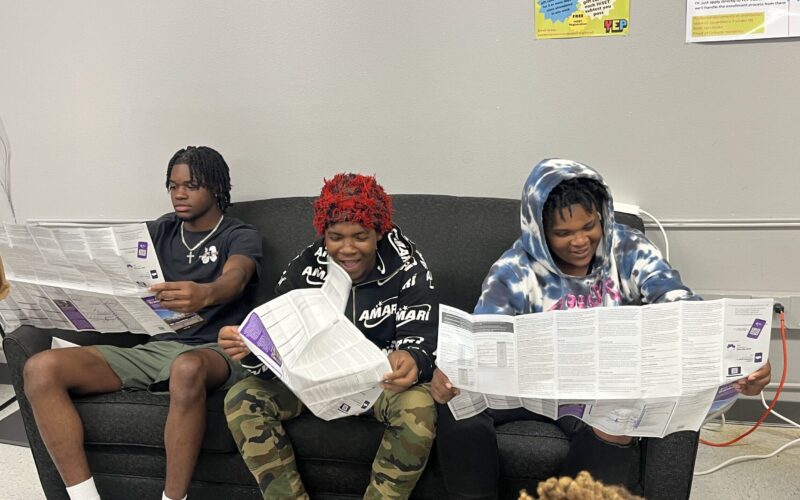

Most transit agencies rely on fare revenue to fund operations, meaning many are forced into the position of needing to collect fares from the people who can least afford it. To change this paradigm, advocates across the country are fighting for - and winning - programs that allow agencies to zero out fares for youth, removing one of the largest barriers to youth ridership.

Read More