In May 2018, “Let’s Move Nashville,” a referendum to direct billions toward rail and bus expansion throughout the city, was defeated by a 64-36 margin. Pundits pointed to the political scandals of Mayor Megan Barry, the referendum’s primary champion, as the primary reason for the loss at the polls. But the full story is not so simple.

Our new report, “Derailed: How Nashville’s Ambitious Transit Plan Crashed at the Polls – and What Other Cities Can Learn from it” examines how the Nashville referendum was weakened by rushed, insular planning that produced a transportation package out of touch with the needs and desires of Nashville residents. Synthesized from more than 40 interviews with people involved in all aspects of the referendum, “Derailed” identifies key lessons for elected officials, agency leaders, and transit advocates seeking to bolster transit at the ballot box.

Ballot measures can be among cities’ most powerful tools to expand access to fast, frequent, reliable transit service. But they aren’t easy to win. Transit campaigns will be stronger if advocates draw lessons not just from prior successes, but from past failures as well.

With places including Austin, Cincinnati, and San Antonio asking voters to fund transit in 2020, the Nashville story is instructive.

Nashville’s crane-filled skyline reflects its recent growth

The rise and fall of “Let’s Move Nashville”

Metro Nashville, population 700,000, is one of the fastest-growing regions in the nation. But its transit system is underdeveloped, consisting of a limited network of low-frequency, low-ridership buses.

Megan Barry was elected mayor in late 2015 and quickly made transit her top priority. After gaining authorization in 2017 to fund transit with a ballot measure, the Barry administration spent four months selecting projects. That fall, they unveiled the $8.9 billion Let’s Move Nashville plan and launched the accompanying campaign, Transit for Nashville.

Barry was overwhelmingly popular at the time, and polling suggested that raising taxes to fund transit expansion had majority support in Metro Nashville. But there was also an undercurrent of concern over gentrification and displacement, widespread construction, and who was benefitting from the changing city. A coalition opposing the referendum, No Tax4Tracks, launched in early 2018 and effectively tapped into this sentiment.

Barry was the only real public face of the Transit for Nashville campaign. When she and one of her bodyguards came under scrutiny for misusing public funds in January 2018, she resigned less than six weeks later, throwing the campaign into disarray.

In the ensuing months, No Tax4Tracks was able to build a coalition of tax-skeptics, seniors, and African American residents. The campaign’s African American spokesperson, jeff obafemi carr, painted Let’s Move Nashville as an opportunity for the rich to get richer, at the expense of working-class people and people of color. He drew connections between the plan’s high price tag and an implication that working-class Nashvillians would be subsidizing light rail improvements for tourists and newcomers. Transit for Nashville was never able to establish enough trust with the public to respond effectively to these allegations.

On May 1, 2018, the Let’s Move Nashville transit funding referendum failed by a huge margin of 36 percent “for” to 64 “against.”

Nashville’s Mayor Megan Barry introduces the Lets Move Nashville plan to reporters in 2017

So what went wrong?

The sources interviewed for “Derailed” identified three core reasons the campaign could not withstand Mayor Barry’s fall from power.

Insularity. Project selection for the Let’s Move Nashville plan was largely shaped by the mayor’s office and Nashville’s business community, relying selectively on recommendations from a 2016 long-range plan called nMotion.

But while the 2018 ballot measure called for a similar level of investment in light rail as nMotion recommended – five corridors at a cost of $3.1 billion – it funded less than 20 percent of the bus service. Many Chamber of Commerce members wanted light rail to help concentrate growth along corridors targeted for development. Members of the mayor’s planning team also felt that light rail would be necessary to attract new riders in an environment where the bus is often described using racially coded language and viewed as being a lifeline service.

In developing the political strategy for Let’s Move Nashville, campaign staff did not stress-test the plan with residents or community leaders. Though the campaign coalition was nominally led by co-chairs who represented key constituencies, they were not in fact empowered to make decisions or influence strategy.

The absence of meaningful public engagement also dampened support for the plan among would-be allies. The Chamber of Commerce’s dominant role in the political campaign made many observers suspect the plan was driven by business leaders and real estate speculators, rather than by a broad public interest in improving transportation access.

Haste. The Chamber of Commerce recommended that the referendum be held in the off-cycle May elections of 2018. While turnout in these elections tends to be low, the voter base tends to lean Democratic, anchored by high African American turnout, and Mayor Barry’s poll numbers were high among African American voters during the planning phase for the referendum. The May date also supported Mayor Barry’s desire to move as quickly as possible and address Nashville’s transportation challenges before she ran for reelection in 2019.

But this decision gave the mayor’s team very little time to make a series of high-stakes planning decisions, complete detailed engineering, and finalize the funding strategy and financing plan. This urgency also came at the expense of robust public engagement. The Mayor’s office assumed that the Nashville MTA’s 2016 public outreach for the nMotion plan had been sufficient. But participants in that process were not representative of Nashville’s voting population, and people of color were significantly underrepresented.

If the election had been held a few months later, civic leaders might have had more time to build the kind of relationships that a strong coalition requires.

Taking African American support for granted. African Americans comprise 29% of Nashville’s population and half of its transit ridership. But the mayor’s lackluster response to issues affecting Nashville’s African American community sapped support for the referendum in the year leading up to the election.

Housing advocates, for example, were dissatisfied with the city government’s track record of implementing plans to increase and preserve affordable housing stock. They felt the mayor’s efforts to align housing policy with the transit referendum were too little, too late. When the Transit for Nashville campaign failed to engage African American residents in its outreach, organizing structure, and messaging, No Tax4Tracks filled the void.

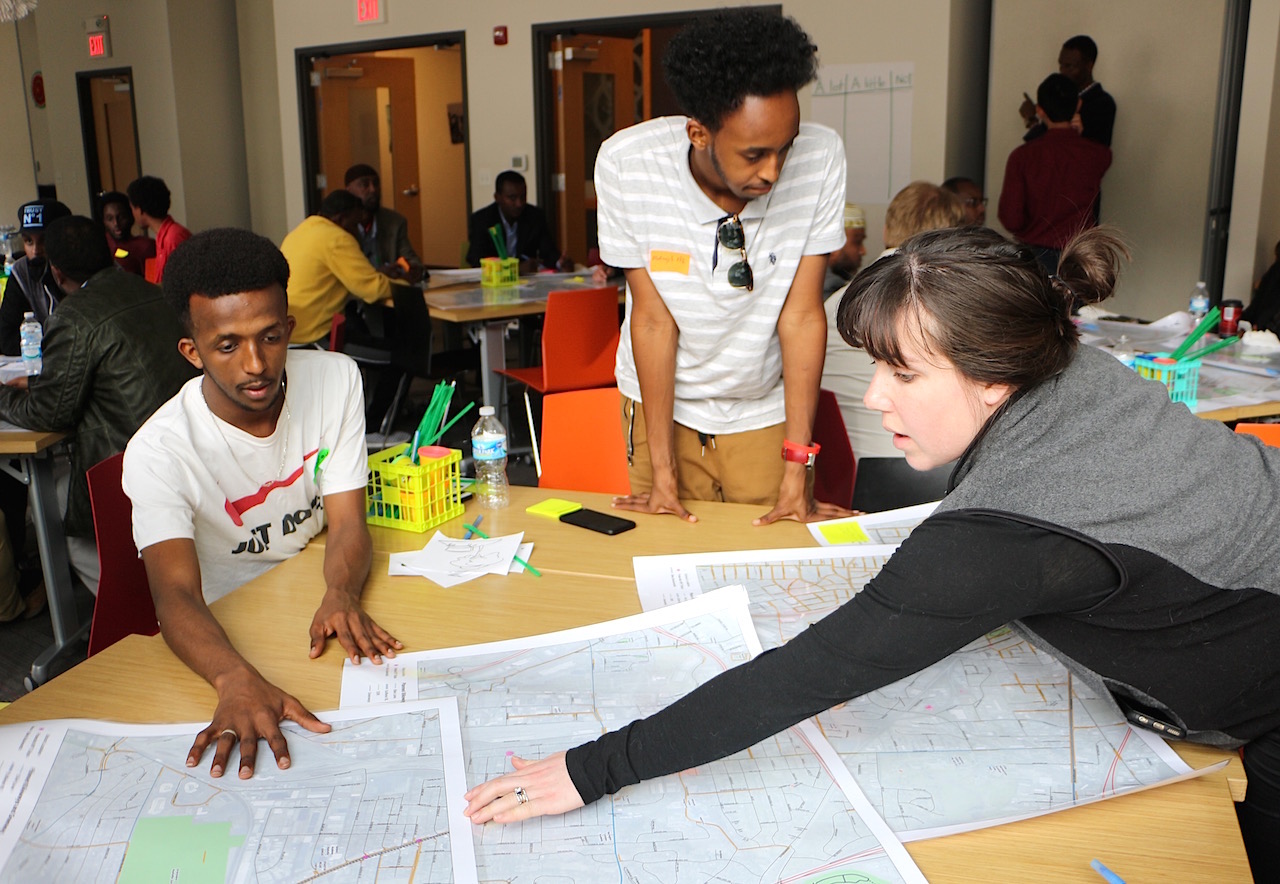

Authentic community engagement is key to building strong coalitions

Learning from Nashville’s mistakes

For a city of Nashville’s size, the scale of ambition in the 2018 transit referendum would have been transformative. Present and future Nashvillians would have benefited from more frequent service throughout the existing transit network and from high-capacity transit lines carrying tens of thousands of people every day.

Yet a resounding majority of voters rejected the plan, either because they had not been convinced of the benefits, did not trust government to deliver those benefits, or did not believe they were worth the proposed tax increases.

Transit advocates in Nashville and elsewhere should learn from this loss. While no transit referendum is easy, Let’s Move Nashville leaders made avoidable strategic mistakes that eroded public trust. It’s likely that a future transit campaign that prioritizes the need of current transit riders, takes the time to convince residents of the benefits of transportation investments, and deeply engages residents—particularly those who come from low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, would result in a different outcome.

Sound transit planning sits at the intersection of political savvy, technical expertise, and a genuine understanding of what residents and transit riders need. Seeking such understanding can be hard work, but the political success of efforts to expand and improve transit depends on it.

Read the full report here.

The Red Line Project Could Transform Access to Opportunity for Baltimore’s Transit Riders

The Red Line Project Could Transform Access to Opportunity for Baltimore’s Transit Riders

This piece was co-authored by TransitCenter, the Central Maryland Transportation Alliance and Willem Klumpenhouwer, a public transit research consultant. The...

Read More How Long Until Atlanta Transit Riders Get More MARTA?

How Long Until Atlanta Transit Riders Get More MARTA?

Four years after the More MARTA referendum, what improvements are now tangible for Atlanta transit riders, and what can riders expect to see in the next four?

Read More