More than 20 years after planning began for Oakland’s Tempo Bus Rapid Transit route, the project finally opened on August 9th. The nearly 10-mile line runs along International Boulevard, a commercial thoroughfare between uptown Oakland and the city of San Leandro to the south. Riders now benefit from 5- to 10-minute headways throughout the day, bus-only lanes, off-board fare payment, all-door boarding, and comfortable, canopied stations.

The corridor is one of the busiest in AC Transit’s bus network. In non-pandemic times, the route is projected to draw 25,000 riders a day, some 10% of AC Transit’s total ridership. Substantial portions of the Tempo corridor are home to low-income, Black, and immigrant Oaklanders who rely on transit.

Tempo is undeniably a beneficial transit project that will bring measurable improvements to the people who use it. Service will be faster and more reliable for tens of thousands of daily riders. But why did it take two decades to build?

“On one hand you feel great that it’s finally done, but on the other hand I’m still so frustrated that it took so long,” said Darrell Owens, a transit advocate who lives in Berkeley. “You can’t really make climate arguments that hey, we need to get people off of driving to save the climate, to save the earth and reduce carbon emissions from vehicles, which are the majority of our emissions in the Bay Area. You can’t do that if it takes 20 years to build a BRT lane.”

The slow pace of BRT implementation is especially notorious in the Bay Area — only two of the region’s five BRT projects in planning since the early 2000s have been completed. But in many ways the Tempo story exemplifies problems that affect corridor-based transit improvements throughout the U.S.

American cities and transit agencies should review these projects with a critical eye, assess what went wrong, and adjust strategies in order to deliver better transit service without making riders wait year after year before they see the benefits.

BRT is often conceived as a faster, cheaper way than light rail to upgrade a transit route. But permitting and environmental review, complicated power-sharing agreements among different jurisdictions, and a lack of internal capacity to deliver big projects can slow down the process and add expense. And while there’s tremendous value in the components of BRT — frequent service, bus lanes, faster boarding, transit signal priority — gradually adding them one corridor at a time can divert energy from more systemic approaches to transit improvement that benefit more people, faster.

Tempo’s planning and construction spanned the Great Recession, the subsequent Bay Area tech boom, and the current COVID pandemic. Advocates involved with the project say that over that time, it became both a vessel for gentrification fears and a reminder that improvements weren’t arriving quickly enough for East Oaklanders whose transportation challenges had long been neglected. When Tempo eventually limped across the finish line, four years behind schedule and $50 million over budget, the victory felt muted.

AC Transit initiated the project in 1999, studying the feasibility of providing new or improved transit service along the 15-mile Berkeley-Oakland-San Leandro corridor. The agency opted to move forward with a suite of BRT improvements in 2002. From the outset, the project faced obstacles.

“Tempo was a complicated project because it was groundbreaking in the way it was organized, being managed, and implemented,” says Joél Ramos, who led public engagement for the project in his former role as community planner for the advocacy organization TransForm. “There really isn’t another project like it that traverses multiple jurisdictions. It was on a Caltrans highway, managed by AC Transit, in partnership with BART. The technical advisory committee looked like a United Nations meeting.”

While AC Transit was the lead construction agency for the project, in practice authority was fractured. AC Transit wasn’t in charge of permitting, for instance, which required coordination between multiple agencies. And because International Boulevard is owned by Caltrans, California’s state department of transportation, it was often unclear which agency had final decision-making power. “To get consensus and agreement on anything took so much heavy lifting,” said Ramos.

AC Transit had no prior construction experience — it was exclusively a bus service provider. The agency relied heavily on a revolving door of outside consultants who would “come in and botch the job, and then get fired,” said Ramos. Tempo also put the agency in the unfamiliar position of conducting public outreach for a major street redesign. TransForm acted as the main bridge between the agency and the public.

“BRT was a foreign concept in East Oakland,” says Clarrissa Cabansagan, director of programs at TransForm. “And the length of the corridor and the sheer number of businesses and various stakeholder groups made for a longer, drawn-out process.” The slow pace allowed doubts to creep in. With a limited number of public champions for the project, the benefits for riders often got swamped by bad press.

Changes made during this process did not prioritize the needs of bus riders. Owens points to the decision in 2011 to eliminate the Berkeley portion from the project in response to Telegraph Avenue merchants’ complaints about parking loss. “I’ve been riding AC Transit since I was a kid,” he said. “As a rider, I don’t feel like any of my concerns are ever heard. It was obvious with the BRT project. Every single time you talk about Bus Rapid Transit, the people at the table are always business groups and planners and homeowners who have opinions. It’s never riders.”

Aversion to parking loss wasn’t limited to Berkeley. While International Boulevard has relatively high transit ridership, the outer stretches of the corridor are car-oriented. Cabansagan said it was difficult for many people to see how they would benefit from the new “green” transit project. They were also wary of the potential displacement that would arise from the investment. “We were able to get enough business support to get the project in the ground, but there was still an education gap. For communities to thrive and sign onto these projects readily, investment after investment, we haven’t brought the right folks along.”

In 2016, Oakland and AC Transit created a program to provide financial support and guidance to businesses affected by ongoing construction and parking removal. But Ramos says the $300,000 that was ultimately doled out was insufficient, and some businesses closed before they could reap benefits from the new line.

Ramos believes transit improvements can be implemented faster with a more incremental and nimble approach. “I think AC Transit really overreached by going for a three-city, multi-jurisdictional approach,” he said. “During the project, the surrounding community so often just wanted us to do something, like creating a bus lane using cones to see what would happen. With that approach, you can start small, add on, and use data to demonstrate the benefits.”

As Cabansagan pointed out, quick success with interim projects can generate proof that transit improvements work, overcoming initial skepticism. “Getting the right information to the naysayers who had the power to delay the project was the big challenge here.”

“Shiny things like BRT,” which only affect one corridor at a time, might distract from addressing systemwide problems, she added. “If the end goal is, for example, the need for more frequency throughout the system, can you accomplish that through better operations planning?”

Ramos believes agencies should be humble about their limitations, and hire trusted outside messengers to conduct public engagement. “As planners, you’re going to have a hard time getting through to these communities that are grappling with gentrification pressures and a legacy of urban and transportation planning rooted in white supremacy,” he said. “I would implore more agencies to find grassroots organizations that are doing the work and empower them to do more and engage the community in the work.” Ramos points to Oakland’s 2019 Bike Plan, developed with the input of 3,500 Oaklanders, as an example of what good engagement looks like in practice.

Centering riders in decision-making will also be key to ensuring future projects don’t get watered down. In July, Owens officially formed a new advocacy group, the East Bay Transit Riders Union, to create a stronger voice for riders.

The group will be showing up to support other BRT projects, including the San Pablo corridor that’s already underway. “We will be speaking in favor of anything that prioritizes bus riders over car users,” he said. “The goal is to make sure that transit gets priority, because so much of transit is oriented around making sure car users aren’t inconvenienced.”

But the group will also be advocating for projects that can be delivered faster than the full BRT package. “Some of the things that East Bay Transit Riders Union is pushing for are things which don’t require a lot of capital investment. Oftentimes it’s as simple as laying down some paint on the streets and just saying ‘this is a bus only lane.’ These are some things that we think are a viable alternative rather than the major projects that we’ll still go along with, but we can’t solely depend on for positive transit yields.”

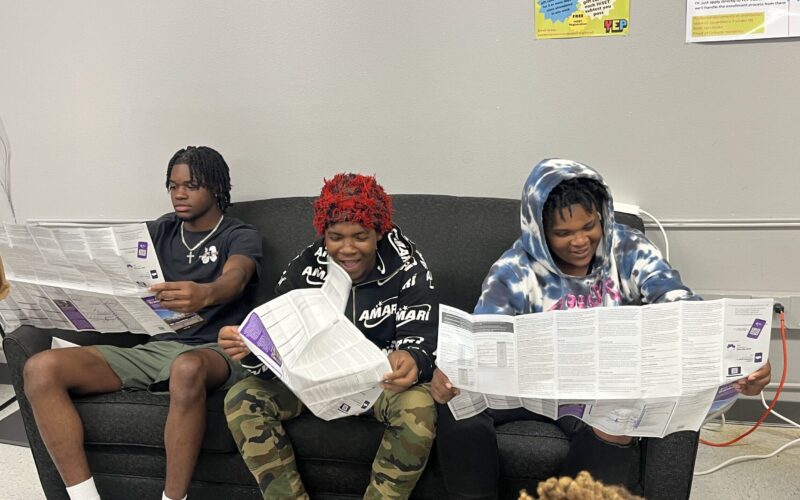

Winning Free Fares for Youth in New Orleans

Winning Free Fares for Youth in New Orleans

Most transit agencies rely on fare revenue to fund operations, meaning many are forced into the position of needing to collect fares from the people who can least afford it. To change this paradigm, advocates across the country are fighting for - and winning - programs that allow agencies to zero out fares for youth, removing one of the largest barriers to youth ridership.

Read More LA is (Not-So) Quietly Adding a LOT of Bus Lanes

LA is (Not-So) Quietly Adding a LOT of Bus Lanes

Thanks to the persistent work of local transit advocates, LA Metro is laying down 30 miles of bus lanes in 2023, pushing the total number of bus lanes in LA County to 40 miles.

Read More