Press:

Nashville Business Journal: Report details demise of Nashville’s $5.4 billion transit plan

WPLN News – Nashville Public Radio: Why Did Nashville’s 2018 Transit Plan Fail? New Report Dishes Out Sharp Criticisms

News Channel 5 Nashville: Report: 2018 transit plan failed due to rushed, insular planning and other things

Streetsblog New York: Learning from Nashville’s Failed Transit Measure

Good Intentions, Failure at the Ballot Box

In 2018, an ambitious plan to expand Nashville’s public transportation system crashed at the polls. The story of how the campaign came apart is relevant far beyond the Music City. Transit in Nashville faces challenges similar to those in other American cities, particularly across the Sunbelt. Nashville’s streets have been engineered and designed to prioritize cars at the expense of walking, biking, and transit. After decades of sprawling land-use development, population and job densities in many areas are too low to support high-quality transit.

A legacy of discrimination in housing and transportation policy has segregated the city’s neighborhoods. Public transit is chronically underfunded,

and the prospects for long-term financial resources from the State of Tennessee are slim. Transit referendums can be among cities’ most powerful tools to overcome these challenges. And while it is rarely easy to win a transit referendum, cities, counties, and regions across the country have

succeeded. Yours can, too—but you should take care to learn not only from those successes but from the setbacks.

Take Metro Nashville, a consolidated city-county government of nearly 700,000 residents, the capital of Tennessee, and one of the fastest-growing metro areas in the nation. With rapid growth and booming downtown tourism, “traffic” ascended to the top of residents’ list of concerns in 2017, edging out affordable housing and education. Yet the following year, proponents of public transportation lost a transit funding vote by large margins.

Local leaders had long recognized the region’s growing transportation challenges. Following then-Mayor Karl Dean’s withdrawal of a controversial rapid bus line in early 2015, the Nashville Metropolitan Transit Authority (since rebranded as WeGo Transit) repurposed federal grant funding to perform a comprehensive planning process dubbed nMotion. The nMotion process included more than a year of public meetings, surveys, and technical analysis, and generated a regional transportation plan, published in 2016, that continues to inform WeGo Transit’s priorities.

Nashvillians elected Megan Barry as the city’s first female mayor in late 2015. Barry made transit her administration’s highest priority, working with the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce, state legislators, and others to enact legislation (the IMPROVE Act) that would allow Nashville and several other Tennessee cities and counties to run ballot measures proposing tax increases to fund public transit. Immediately after the IMPROVE Act’s passage in May 2017, the Barry administration conducted an internal four-month planning process to choose projects for a ballot measure. This planning process culminated in the launch of the Transit for Nashville coalition in September 2017—formed to support a referendum—and subsequent release of the Let’s Move Nashville plan in October. At this time Mayor Barry was overwhelmingly popular, and polling suggested that raising taxes to fund transit expansion had majority support in Metro Nashville. Parallel to the mayor’s planning process, the chamber of commerce laid the groundwork for the Transit for Nashville campaign, hiring consultants and signing off on the campaign’s overall strategy.

The campaign launched in a charged political atmosphere. Nashville’s rapid growth had bred resentment around many of the local dynamics that accompany growth––more expensive housing, widespread construction, slower traffic, significant in-migration. Meanwhile, the heightened national focus on issues of social and racial justice had changed local political dynamics in ways that Nashville leaders did not anticipate. Combined with declining transit ridership in Nashville and beyond, the ground was fertile for bad-faith critiques from conservative think tanks and so-called “experts.”

Mayor Barry was the public face of the Transit for Nashville campaign until she and one of her bodyguards came under scrutiny for the misuse of public funds in January 2018. The timing could not have been worse: the opposition campaign, NoTax4Tracks, launched almost simultaneously with a focus on eroding trust in the Let’s Move Nashville plan among African American voters and tax-skeptics. The mayor resigned less than six weeks later, jeopardizing the referendum’s chances of success and throwing the Transit for Nashville campaign into disarray.

On May 1, 2018, the Let’s Move Nashville transit funding referendum failed by the spectacular margin of 36 percent “for” to 64 “against.”

Signs did not point to such a lopsided defeat. When polled in the months leading up to the vote, more than 70 percent of Nashvillians claimed to support tax increases to fund transit. The “for” campaign out-fundraised the “against” campaign by roughly a factor of three, with more than a six-month head start. The political campaign, backed by the mayor’s office and the chamber of commerce, made data-driven decisions at each step of the process.

News coverage of the vote cited Mayor Barry’s resignation, an anonymously funded opposition campaign, and the get-out-the-vote effort by the local chapter of the Koch brothers–funded Americans for Prosperity. But a 64–36 margin is large enough to suggest that several other factors were at play.

So, what happened?

- Insularity. In the referendum planning process, Mayor Barry and her planning team assumed they knew what their constituents would vote for based on the existing nMotion long-range plan, without stress-testing the referendum plan with either residents or community leaders before its release. In developing the campaign’s political strategy, campaign staff ignored or failed to seek out both stakeholder and expert input. The coalition appointed co-chairs who led the effort in name only. Though they represented key constituencies and were authentic spokespeople, they were not empowered to make decisions or influence strategy. The campaign’s strong, direct ties to the mayor caused the campaign to lose its footing when the mayor’s scandal hit.

- An inconsistent strategy. The campaign strategy depended on African American support, but the mayor’s office alienated African American voters repeatedly during the year leading up to the election. Growing concerns about gentrification and displacement––and the mayor’s housing plan ––highlighted the region’s affordable housing shortage. Housing advocates were dissatisfied with the city government’s track record of implementing plans to increase and preserve affordable housing stock, and advocates felt the mayor’s efforts to align housing policy with the transit referendum were too little, too late. When the Transit for Nashville campaign failed to focus on African American voices in its outreach, organizing structure, and messaging, a strong, targeted opposition campaign filled the void. These dynamics undermined Transit for Nashville’s equity-focused arguments.

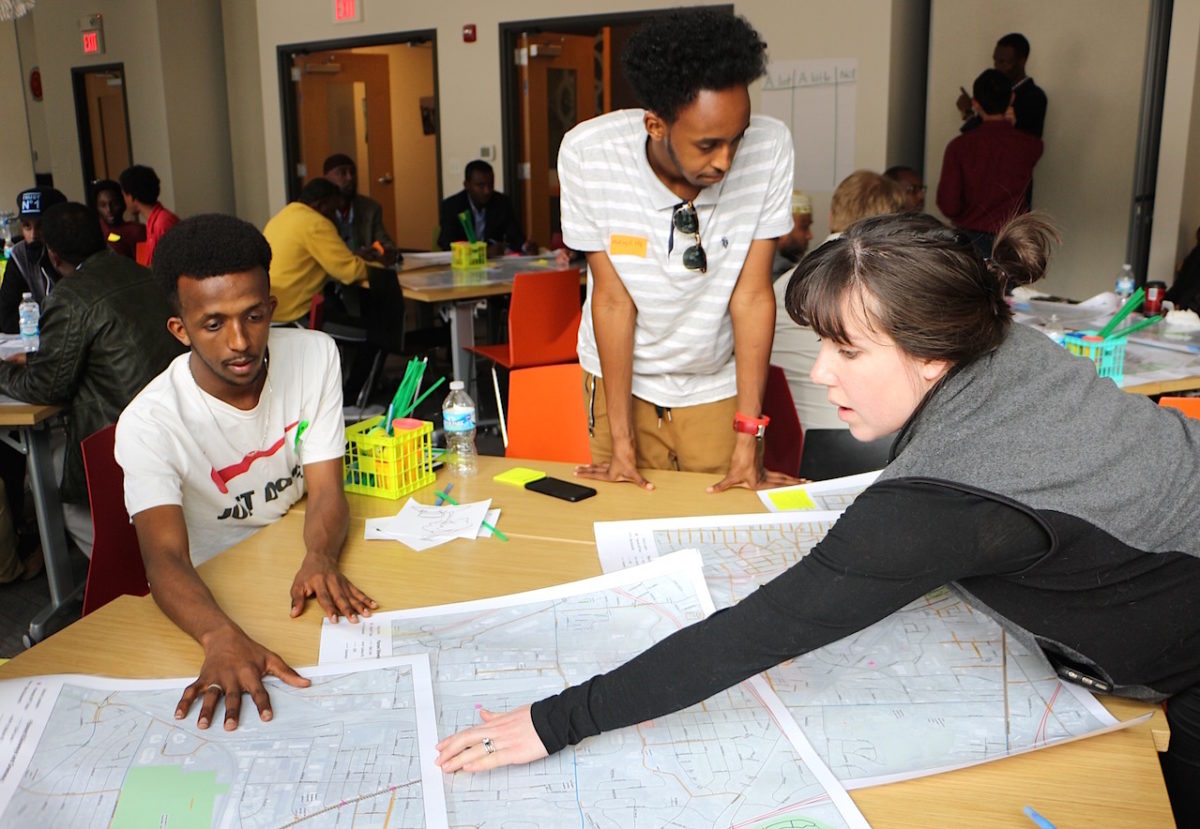

- Haste. With only eleven months between the passage of the IMPROVE Act and a public vote, the mayor’s office prioritized speed. This urgency came at the expense of robust public engagement, with the mayor’s office in effect assuming that the Nashville MTA’s nMotion public outreach process had been sufficient. Participants in that process were not, however, representative of Nashville’s voting population, and people of color were significantly underrepresented. Those who participated in nMotion surveys weighed in on Nashville MTA’s long-range plan, but not on the specific projects they would be willing to pay for via specific tax increases. Lack of public engagement exacerbated the campaign’s insularity.

These factors combined to erode already fragile trust in government across the May 2018 electorate. Early strategic decisions by the mayor’s office merit particular scrutiny, because the consequences reverberated during the planning process and the political campaign. Decisions about whom to consult, which goals to strive for, and when and where to hold the election shaped the plan and the campaign’s ability to earn “yes” votes.

Most strategic oversights were rooted in one flawed assumption: the decision-makers in both groups thought they understood what Nashville’s communities wanted. While the mayor’s office trusted the nMotionrecommendations on light rail, the Let’s Move Nashville plan called for funding less than 20 percent of the bus service recommended by nMotion. Both the mayor’s office and the Transit for Nashville campaign based strategic decisions on voter modeling and polling, but often at the expense of allies’ and staff members’ subject-matter expertise. Planning and campaign team leaders were more out of touch with Nashville voters than they realized, in large part because they relied too heavily on engagement with “grasstops” leaders.

Sound transit planning sits at the intersection of political savvy, technical expertise, and a genuine understanding of what residents and transit riders need. Seeking such understanding can be hard work, but the success of future referendums depends on it.

This case study, Derailed, identifies key lessons for elected officials, agency leaders, and transit advocates drawn from Nashville’s experience. The material is synthesized from more than forty interviews with stakeholders across the spectrum of involvement in the Let’s Move Nashville planning process and referendum––including Mayor Barry’s planning team, the political campaign, coalition members, paid and volunteer advocates on both sides of the issue, journalists, and elected officials.

Lessons for Crafting a Plan

With the best intentions, Mayor Barry and her planning team made several early strategic decisions in haste, potentially at great cost to the ultimate referendum results.

For starters, Mayor Barry’s planning effort was guided by a group of trusted advisors and appointed officials whose relatively homogeneous worldview was out of step with the priorities of Nashville voters. The plan they developed drew heavily from the Nashville MTA’s nMotion long-range plan, which recommended mainly investing in light rail. The Nashville MTA’s nMotion public engagement report found that current transit riders were the least likely to support this plan (preferring a greater emphasis on bus improvements), suggesting that this recommendation stood on shakier ground than the mayor and her advisors realized.

Mayor Barry wanted to move through the referendum process as quickly as possible, and the planning team wanted to carefully control the plan’s messaging and release following the long, drawn-out defeat of a previous Nashville transit project. For these reasons, the mayor’s staff conducted financing and engineering work behind closed doors. The absence of meaningful public engagement would go on to breed resentment and dampen support for the plan among would-be allies, opening the door for transit opponents to more credibly offer bad-faith critiques.

The referendum planning process requires civic leaders to seek the right balance between navigating the local political landscape and prioritizing meaningful transit improvements.

Navigating the local political landscape:

Act with appropriate urgency

- Mayor Barry ensured progress by convening key advisors and senior staff, giving them a mandate to bring something ambitious to voters, and setting similarly ambitious deadlines. But this time pressure also forced the Barry administration to make decisions in haste, contributing to strategic choices, e.g., a plan dominated by light rail investment, that in retrospect appear misguided.

Include and foreground a diverse range of voices in the decision-making process

- While the Barry administration as a whole was quite diverse, the team that designed the Let’s Move Nashville plan included no people of color with decision-making power.

Build your plan on a foundation of inclusive, meaningful public outreach

- The absence of public engagement made it impossible for Mayor Barry’s team to gauge how their proposal would be received by voters. Instead, the planning team worked behind closed doors, relying on the nMotion plan, which drew from surveys that dramatically underrepresented people of color.

Choose an election and a geographic scope that will maximize your likelihood of success

- Under Tennessee’s IMPROVE Act, Metro Nashville can only run county-wide transit ballot measures. While the county as a whole is fairly progressive, land use outside central Nashville is not transit-supportive, creating unavoidable political challenges.

- The mayor decided to put this initiative on the ballot at a May 2018 election based on modelling and polling analysis, but this decision created significant uncertainty regarding turnout and allowed opponents to focus exclusively on transit (as opposed to the state or federal races that would have drawn attention in a November election). Modelling suggested there would be high African American voter turnout in this election, but both the mayor’s office and the Transit for Nashville campaign failed to prioritize engagement and outreach in African American communities.

Prioritizing meaningful transportation access improvements:

Make improving access to high-quality transit the North Star of your planning process

- Although everyone on the mayor’s team wanted to improve transportation access, the final package emphasized light rail projects rather than focusing on bus service improvements, which would have delivered greater access to frequent transit at a lower cost to residents.

Place equity at the heart of the transportation plan

- Transit investments can advance equity in a variety of ways, but the lack of public engagement and perceived over-emphasis on light rail––especially given concerns about housing affordability, gentrification, and displacement––eroded public trust, particularly among Nashvillians of color.

Lessons for Crafting a Campaign

The Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce played a critical role in the referendum organizing effort. The chamber maintained strong relationships with the mayor’s office, funded study trips to other cities with major transit investments, and conducted multiple studies to lay the groundwork for what would become the Let’s Move Nashville plan. The chamber led a successful fundraising effort, hired the campaign consultants who managed the Transit for Nashville political campaign on a day-to-day basis, founded the Transit for Nashvillecoalition, and drew 136 organizations into that coalition.

In retrospect, however, the chamber’s role in Transit for Nashville was too dominant––without more diverse perspectives in the decision-making process, the chamber’s organizational mission to represent the business community created blind spots that weakened the campaign. The chamber failed to create space for other groups to lead.

To develop and execute a successful campaign plan, civic leaders need to build strategic, flexible campaign structures that reflect the diversity of the voter base and work with community partners to deliver clear, consistent messages to voters.

Build strategic, flexible campaign structures that reflect the diversity of the voter base

Align campaign organizing and leadership structure with strategic goals

- The Transit for Nashville campaign’s leadership structure was muddled and lacked clear accountability, with the lead campaign consultant and campaign manager hired separately. Staff at the lead PR agency for the campaign were also mostly part-time, which meant that, especially during Mayor Barry’s scandal, their attention was divided. In retrospect, the chamber regretted not including stronger financial incentives in their consultant contract––both to reduce budget overruns and to add a direct financial incentive to win.

Include and foreground a diverse range of voices in the decision-making process

- There were no African American people in decision-making roles on the Transit for Nashville campaign, and campaign consultants charged with outreach to communities of color often felt their concerns and ideas were ignored.

Build flexibility into your campaign so you can adapt to changing circumstances

- The Transit for Nashville campaign stuck to a rigid plan, even as circumstances rapidly changed. The campaign’s unwillingness to incorporate new information coming from consultants conducting outreach in African American and Latinx neighborhoods, for example, diminished staff morale and limited the ability to adapt.

Anticipate an organized opposition

- Many of the opposition campaign’s strategies and messages were designed to mislead. Most of these messages were not new, but Transit for Nashville did not anticipate the opposition’s tactics. Scrappy, strategically targeted opposition assisted by local Koch-funded groups and conservative think tanks is increasingly common in transit referendums.

Work with community partners to deliver clear, consistent messages to voters:

Build an independent and inclusive transit advocacy coalition

- The Transit for Nashville coalition looked broad on paper but was shallow in practice––organizational leaders were on board, but not necessarily their employees or staff. This was partly because the coalition was managed by the political campaign, rather than by coalition members. Coalition members’ responsibilities were at times unclear, and the most active members had limited experience working together.

Don’t take key constituencies for granted

- The May 2018 election was chosen in large part because it typically sees higher African American turnout than other elections in Nashville (nearly 30 percent of Nashvillians are African American). Yet the opposition campaign dramatically outperformed Transit for Nashville in building trust in African American communities, even with significantly fewer resources, because they identified a compelling spokesperson and targeted their campaign investments accordingly.

Build a diverse bench of spokespeople

- Mayor Barry’s resignation put into stark relief how dependent the transit campaign had been on her popularity to carry the referendum forward. Without a bench of empowered, trusted spokespeople, the campaign scrambled and failed to find viable replacements.

Define the narrative with consistent messages that clearly convey the plan’s likely benefits

- Transit for Nashville ceded a significant timing advantage to opponents. NoTax4Tracks was able to get advertisements up on TV first, causing Transit for Nashville to react and play defense rather than proactively setting the terms of the referendum debate.

- The campaign’s strong emphasis on traffic reduction was fairly (if disingenuously) criticized by opponents, and a rotating roster of messengers failed to consistently frame a positive vision for what successful transit investment would do for Nashville.

- Many successful transit referendums include road spending in part to preempt criticism about traffic reduction. Tennessee’s IMPROVE Act requires that funds be dedicated to transit-related improvements, which may include sidewalk and adjacent road projects. The project list could have included more projects aimed at improving first- and last-mile access to transit, and the campaign could have more intentionally emphasized those benefits in their messaging.

There is much to admire in Nashville’s effort––for a city of its size, the scale of transit ambition was extraordinary and would have transformed the city. The mayor’s leadership and vision were bold, and many of Nashville’s civic leaders poured heart and soul into a plan they believed in. Present and future Nashvillians would have benefited from more frequent service throughout the existing transit network and from high-capacity transit lines carrying tens of thousands of people every day.

Yet voters rejected the plan, either because they did not understand these benefits, did not believe those benefits would be appropriately shared, did not trust government to deliver those benefits, or did not believe they were worth the proposed tax increases.

The leaders who step up next to pursue dedicated, long-term transit funding in Nashville and beyond can take some comfort in knowing that failure in 2018 was not inevitable. While no transit referendum is easy, Let’s Move Nashville leaders made avoidable strategic mistakes that eroded public trust.

There is no silver bullet for building trust––but doing so will require the humility to recognize that community members hold unique expertise and insight into their own needs and challenges. Civic leaders must include, listen to, and empower residents––particularly those who come from low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, who have long been excluded from public planning and policy-making processes––to influence decisions that tangibly affect their lives.

Read the full report.