Introduction

Hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers require elevators to access the subway every day: people with disabilities, parents pushing strollers, travelers carrying luggage, and residents suffering from an injury.

These elevators break down often, rendering even fewer stations accessible to those with mobility impairments. The

paucity of accessible stations combined with this high degree of unreliability makes journeys unpredictable, vastly extending travel times, rerouting riders, and making trip planning impossible. These elevators are also notoriously dirty and malodorous, a persistent problem that is symptomatic of overall neglect. In a city full of elevators and elevator experts, subway elevators that travel only a few “floors” each are constantly going out of service, and no one is held accountable.

Nearly 10% of New Yorkers have a disability, and 13% of New Yorkers are 65 or older. This latter population is projected to increase to 15.5% – nearly 1.4 million New Yorkers– by 2030. Both groups will require more accessible subway stations to reach social engagements, jobs, housing, schools, and health care. But they are not the only groups affected – hundreds of thousands of other New Yorkers require elevators to access the subway every day: parents pushing strollers, travelers carrying luggage, or residents who are suffering from an injury.

Press

Streetsblog: The MTA Board Standing Up for Riders? It Could Happen.

Streetsblog: If You Can’t Take the Stairs, Only 23 Percent of Subway Stations Are Accessible — on a Good Day

Vice: New York’s Subway Is Hell for Riders with Disabilities

Spectrum News: Report: Many MTA subway riders with disabilities still denied access

CityLimits: City Buses Are Slow, Unreliable and What Many Disabled & Aging NYers Rely On

Curbed: The NYC subway has an accessibility problem—can it be fixed?

AMNY: Report: Many MTA riders with disabilities still denied access , July 20, 2017

NY1: MTA gets heat over broken elevators, lack of accessibility at subway stations, July 20th, 2017

View the Press Release

The MTA has recently initiated a program to rehabilitate stations, but none of these plans include adding stair-free access to currently inaccessible stations. To ignore accessibility even while closing stations for upwards of six months, inconveniencing entire neighborhoods in the process, is emblematic of the agency’s lack of strong leadership and policy when it comes to providing access to all New Yorkers.

In 1994, the MTA agreed to make 100 “key stations” accessible by 2020. This was part of a settlement that exempted the agency from full compliance with the ADA and the state’s Public Buildings and Transportation Laws. The MTA is currently working to complete the final 11 of these 100 stations in its 2015-2019 capital construction plan. But beyond fulfilling this agreement, there is no plan or policy for making the system more accessible in the future.

The recommendations in this document are designed to remedy these shortcomings.

Goals & Actions

In the short term, MTA leadership must devote far more attention to the issue and create a system of accountability that ends the chronically poor performance of subway elevator service. Governor Andrew Cuomo and Chairman Joe Lhota should immediately create a task force to develop these institutional changes. Additionally, the agency could quickly improve public information and communication to riders, and generate a new accountability check, by establishing an elevator status Application Programming Interface (API). That would allow nimble third party smartphone applications to provide elevator status, and more readily provide data on elevator performance to outside monitors and advocates. The agency should also improve elevator reliability through updated maintenance processes, revised training for elevator repair workers, and renegotiated contracts with equipment vendors.

In the longer term, the MTA Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment and the 2020- 2024 Capital Program should express clear policies and commitments to significantly accelerated elevator installation, with the ultimate goal of a fully accessible subway system. Governor Cuomo, Chairman Lhota, and the MTA/NYCT can make accessibility a priority in these guiding documents, committing the agency to increased elevator access throughout the system with plans to increase accessibility each year, for the benefit of all New Yorkers.

New York's Inaccessible Subway System

New Yorkers who cannot use stairs confront a dramatically different public transportation landscape than those who can.

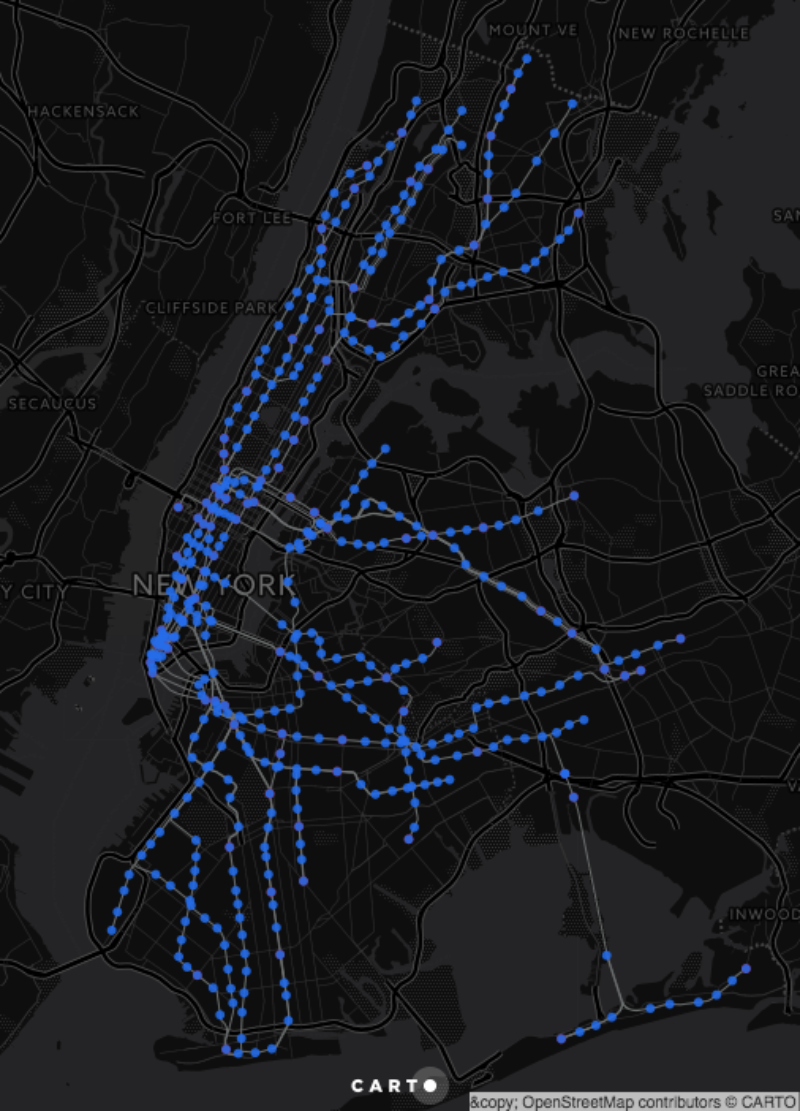

There are currently 110 subway stations – out of 472 total – that are accessible under the ADA.

There are currently 110 subway stations – out of 472 total – that are accessible under the ADA. Eighty-nine of these came from the 1994 “key stations” plan. The remaining stations either saw elevator installation in the course of a major station overhaul, or are new stations associated with recent subway expansion such as Hudson Yards and the Second Avenue Subway.

These stations comprise only 23% of the MTA’s subway stations. This creates severe limitations on the trip-making abilities of those requiring stair-free access. A person who can navigate stairs can travel from any subway station in the city to 471 other stations – a total of 222,312 possible station-to-station trips. But someone requiring an elevator enjoys only 5% as much trip-making opportunity, and consequently finds much of the city out of reach by subway. She or he can reach 109 stations from any particular accessible station – only 11,990 possible point-to-point trips.

There are also several stations that have an elevator, but yet remain inaccessible to people who require stair-free access. In some cases, the existing elevator only connects the street to the mezzanine, or the mezzanine to the platform, but not both. In others, an elevator may get a rider almost all the way to the platform, only to be faced with a short staircase to get the rest of the way. These stations could be made accessible through either the addition of another elevator or the installation of a ramp to complete the connection. Inaccessible elevator stations include the 181st

Street and 191st Street stations on the 1 line, the 57th Street station on the Q line, and the Clark Street station on the 2/3 line.

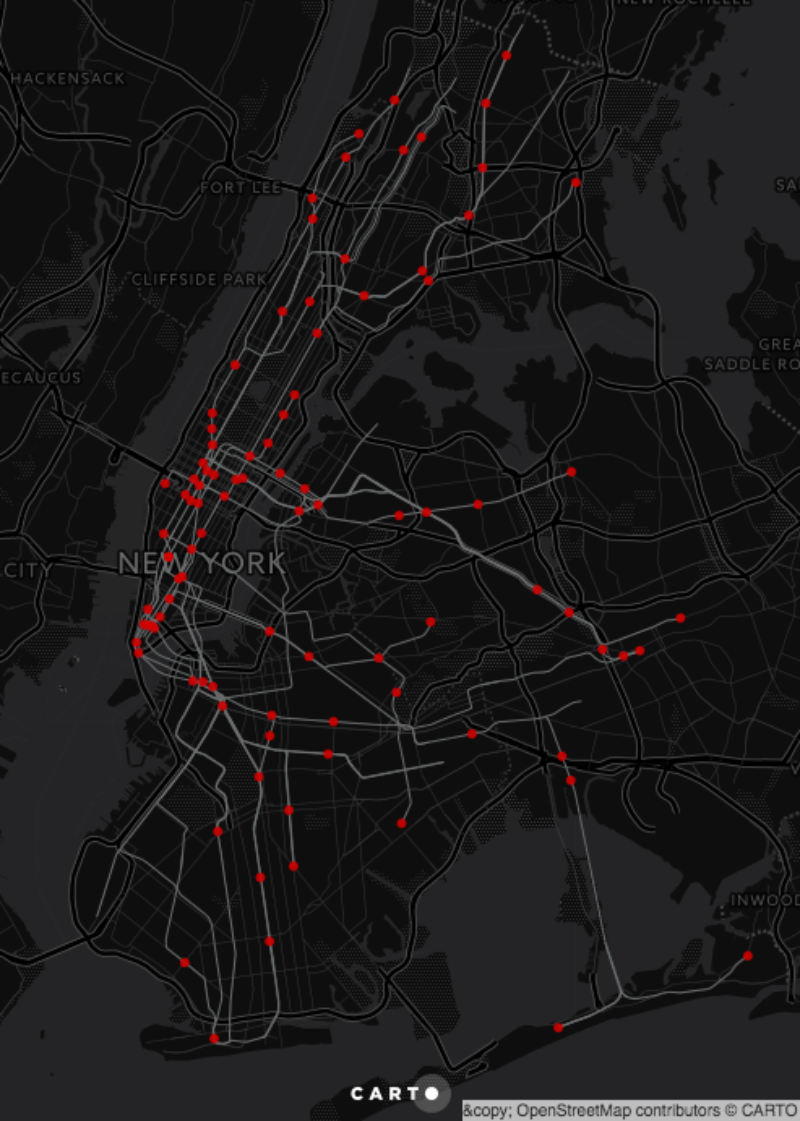

The Plague of Unreliability

Even subway stations that have elevators are often inaccessible because NYC subway elevators are notoriously unreliable. According to MTA data from July 2014 to June 2015, an average of 25 elevator outages occur every day, with 46 outages on the worst day that year, and 7 elevators going out of service on the system’s best day. On average, individual outages lasted 5 hours and 33 minutes, with the longest continuous outage persisting for more than 27 days. This does not factor in long-term elevator shutdowns, which are not recorded in this data. While the MTA reports 96% elevator “uptime” – meaning the equipment is working and serving the public – a 2013 audit report by the NYC Comptroller’s office found that the MTA consistently failed to record some elevator outages in its tracking system. These outages were thus excluded from the MTA’s elevator performance measurement, skewing the uptime number higher. Additionally, a more recent audit completed in 2017 by the City Comptroller found that the MTA does not factor downtime for major repairs into elevator performance reporting, further overstating availability. This finding was also flagged in a 2001 audit by the State Comptroller.

These reporting failures affect the public: when outages are not recorded, they are also omitted from the agency’s real-time elevator status web page, the primary trip planning resource for riders who cannot use stairs. This unreliable and inaccurate information causes additional missed trips, travel delays, and rider confusion. Apart from these reporting failures, the elevator uptime measurement itself is misleading: as there are often at least two or three elevators in a station – one connecting the street to the mezzanine, and another connecting the mezzanine to the platforms – a single elevator outage can render the entire station inaccessible. The rate of station accessibility is far less than the MTA’s reported total elevator uptime.

MTA data also indicates the agency lowered its elevator uptime target from 97.5% to 96.5% in 2010. A year later, even this reduced target was not being reached. More recent data shows that 24-hour elevator availability has continued to trend downward – going from 96.7% in the 4th quarter of 2014 to 95.7% in the 4th quarter of 2016.

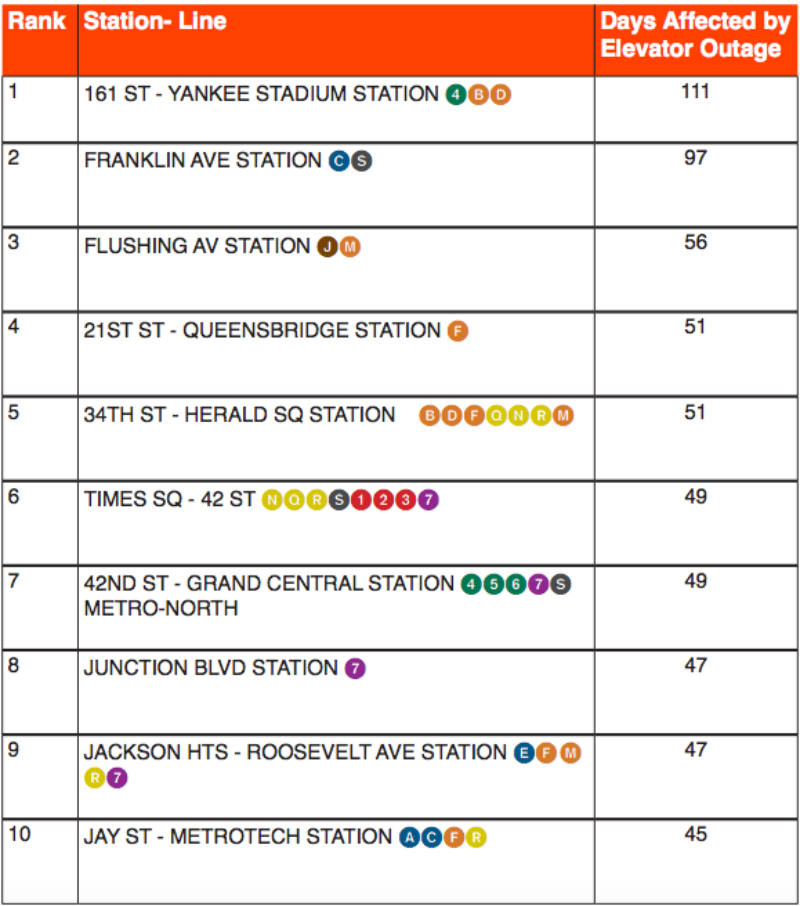

The worst offenders in this category were 161st St Yankee Stadium in the Bronx and Franklin Avenue in Brooklyn, which were affected by elevator outages for 111 days and 97 days, respectively. This list includes some of the busiest stations in the subway system.

Other Cities Have Done It

The Boston T and Chicago CTA urban rail networks, like New York’s subway, are century-plus old systems. Yet they have more than twice the station accessibility, and thus vastly greater trip-making opportunities for people requiring accessible stations. After local leaders empowered agency staff to tackle the issue, 71% of Boston’s subway stations and 69% of Chicago’s rail stations have been made accessible. Both cities have concrete plans to reach 100% accessibility.

The Boston T and Chicago CTA urban rail networks, like New York’s subway, are century-plus old systems. Yet they have more than twice the station accessibility, and thus vastly greater trip-making opportunities for people requiring accessible stations.

These plans and improvements were only possible because elected leaders and senior agency management took a firm position to make accessibility a priority and hold their agencies accountable.

Boston has proven that increased elevator reliability is possible and that institutional change is the key to better results. In 2006, in response to an accessibility lawsuit, the MBTA created a department of System-Wide Accessibility (SWA), which formed a clearinghouse for accessibility-related expertise and project planning. The SWA tracks compliance with the settlement and with the ADA, pushes accessibility-related changes through the agency, and employs undercover workers to test compliance with the settlement.

In 2010, the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) recognized the need to proactively address disability access to its rail system. Through strong leadership from mayor Rahm Emmanuel, the CTA’s president and board created the Infrastructure Accessibility Task Force (IATF) to develop plans to increase accessibility throughout the system. The IATF was composed of mayoral, CTA and Chicago DOT staff, researchers from the University of Illinois, architects, and disability advocates. All contributed time and expertise on a volunteer basis. CTA staff were drawn from the ADA compliance, capital construction, engineering, planning, and rail operations departments.

Recommendations

Rather than develop another set of “key stations” that will likely be outdated in another 25 years, the MTA should consider a faster pace and a more adaptable approach to accessibility. At the current pace of installing new elevators, New York City’s subway stations would not reach 100% accessibility until roughly the year 2100.

At the current pace of installing new elevators, New York City’s subway stations would not reach 100% accessibility until roughly the year 2100.

Governor Cuomo and the MTA leadership have the power to vastly accelerate progress on system-wide accessibility for the NYC subway. Below are high-level recommendations for the governor, the chairman, and the agency.

Accessibility starts at the top with strong leadership and a commitment to making the New York City Subway accessible to everyone. The next Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment and the 2020 Capital Program could be key levers in effecting change, but this reform will need to come at the directions of the Governor, Chairman Lhota, and MTA leadership. These policy guides should prepare the agency to fully accommodate riders who need stairfree access, and to be ready for critical near-future shifts in rider demographics. With the population of New Yorkers who are 65+ expected to increase by 36% by 2030, it’s urgent that their access to and mobility via the subway system be addressed now.

Immediate Actions (3-6 months)

- Incorporate detailed ADA accessibility improvements into the next Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment, which informs the Capital Program

- Set a goal of 100% accessibility, with clear targets and benchmarks

- Introduce and/or improve reliable and frequent inter-borough bus service to serve as a stopgap measure to allow riders to travel between boroughs without having to depend on Access-A-Ride.

- Introduce a faster pace of new elevator construction, such as 15 newly accessible stations a year. This would result in 100% accessibility in 25 years. As an example, Chicago has set a deadline of 20 years to achieve 100% accessibility in its system.

- Make stations accessible that already have elevators (eg. by adding ramps at short staircases), such as at the 181st Street, 191st Street, 28th Street, and Clark Street stations.

- Allocate capital funds to significantly increase station accessibility through 2024 and beyond.

- Design and site elevators to provide equivalent access to and from stations and platforms for riders who need stair-free access as it is for those who do not, specifically in terms of access/egress time and ease of use.

- Institute a policy of including full ADA accessibility as a key element of all future station enhancement plans and long-term (6+ months) station shutdowns

- Increase elevator redundancy at existing accessible stations.

Boston and Chicago have been successful because they created offices with authority and resources that serve as clearinghouses for accessibility initiatives and maintenance. In both cases, accessibility was no longer another checkbox, but rather a priority, with clear targets and standards. A centralized accessibility office is necessary to monitor elevator performance, negotiate vendor contracts, determine station priority for accessibility, and ensure capital improvements are implemented. Most importantly, such an office is the home of the agency’s comprehensive accessibility plan that can inform future capital programs, steering the agency toward systemwide station accessibility and elevator reliability.

- Create a permanent office within the agency dedicated to accessibility oversight and accountability. This office must be given the authority and resources necessary to help the agency achieve, and hold staff accountable to, the milestones leading to 100% subway accessibility, and 99.5% elevator uptime. The MTA could also expand the authority of the existing Office of ADA Compliance to play this role.

- Create a long term plan to reach 100% station accessibility, and stop using cost as an excuse for inaction. Following Chicago’s lead, the MTA could form an internal task force comprised of agency leadership, agency staff, disability advocates, electeds, planners, architects, and designers to assess and determine where elevators are most needed, and what other improvements are needed. Such a task force must have the authority and resources to implement recommendations and to coordinate across the agency. It must also be accountable to the governor and chairman for progress reporting.

- Develop a method for identifying the highest priority stations to make accessible, such as that used by Chicago’s internal accessibility task force. This task force developed a rational scoring method to evaluate the importance of stations based on a set of weighted criteria, including ridership, people with disabilities ridership, senior ridership, paratransit home addresses, population, employment, university enrollment data, senior services and housing, points of interest, and gaps between accessible stations.

- Evaluate concepts for incorporating accessibility into high-ranking stations. This was the second step of Chicago’s station evaluation approach. The task force sketched out different station designs and their estimated costs for each high-ranking station. In their designs, the task force sought to “provide comparable routes to the platform and to exits for customers with disabilities as for customers without disabilities.”

Key to elevator reliability is elevator maintenance. A recent audit by the NYC Comptroller found that the MTA failed to adhere to its preventive maintenance service schedules 80% of the time. Of the preventive maintenance service inspections that were performed, 25% of the required checklists were not completed. These lapses in maintenance procedures result in higher elevator failure rates, and may put passengers at risk. The MTA should take one of two actions to improve its elevator maintenance protocols and success rates:

- Overhaul maintenance and management practices, with a focus on employee retention, as well as better training, tracking, reporting, and accountability; or

- Contract out elevator maintenance operations to a private company that specializes in the field. Whichever path the MTA chooses to take, the following actions must be a priority.

- Increase elevator uptime to greater than 98.5 % within six months.

- Record and report metrics on station accessibility affected by elevator outages.

- Record and report metrics on privately owned and operated elevators serving MTA subway stations.

- Ensure all elevator outages are recorded and reported to the public in real-time.

- Include station accessibility in the agency’s data (GTFS) that is used for trip-planners such as Google Maps.

- Create an interface (API) that allows developers and app-makers to include elevator outages in their apps and send real-time notifications to riders.

- Achieve 99.0% elevator uptime within 2 years.

- Achieve 99.5% station uptime within 3 years.

The current capital program has more than 20 stations slated for overhaul, yet elevator construction is not included in any of these plans. To refurbish these stations, the MTA adopted a practice of shutting down stations completely for a period of several months in order to make improvements quickly. This provides one opportunity to make stations accessible more quickly, taking advantage of the station’s closure and building accessibility features into these enhancement plans. The MTA plans to do this with two stations along the L train, taking advantage of the pending 2019 15-month shutdown of the Canarsie Tube connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan. The agency is not, however, adding elevators or upgrading elevator equipment along the other four stations slated for closure, including the 6th Avenue station, which is entirely inaccessible to people with mobility impairments and yet is a major transfer point between multiple subway lines and PATH. Similarly, the MTA is closing three stations on the R line in Brooklyn for more than six months each to add wifi, lighting, new paint, and other upgrades, but none of these stations are slated to receive elevators.

- Include ADA accessibility in all station renewal or rehabilitation projects.

- Add elevator access to all stations along the portions of the L line that are slated to shut down for 15 months. Those stations that are not currently slated for accessibility improvements include the 3rd Avenue station and the 6th Avenue station.

- Do not award a contract for any design that excludes elevator access in the next phase of Governor Cuomo’s “Station Enhancement Initiative.” The next phase will shut down four stations along the N/W line in Astoria for 6+ months. The stations slated to be modernized are Broadway, 30th Avenue, 36th Avenue, and 39th Avenue, none of which are currently accessible.

Conclusion

George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 with soaring rhetoric, saying the law “promises to open up all aspects of American life to individuals with disabilities – employment opportunities, government services, public accommodations, transportation, and telecommunications.… [It] presents us all with an historic opportunity. It signals the end to the unjustified segregation and exclusion of persons with disabilities from the mainstream of American life.” Twenty-seven years later, the ADA is a dream deferred, with inequality and segregation on full display within the New York City subway system. As Andrew Cuomo strives to transform the city’s subway system into “a world-class transportation network,” he has an opportunity to cement his legacy and create a new historical moment by approaching accessibility head-on – not as a box to check nor a burden to overcome, but as a challenge worth surmounting for the greater good. A city that prides itself on diversity, fairness, opportunity and being in the lead of expanding civil rights should have a way for everyone to physically reach and enjoy the city. In large part, that means accessible subway stations.