Free transit sounds like a utopian fever dream. Imagine being able to hopscotch your city on a bus, never again needing to fumble for your ticket, seeing the dreaded “insufficient fare” message on the fare machine, or forgetting to ask for a transfer.

Fare-free transit has lately been floated as a panacea for solving any number of society’s ills, including climate change, congestion, and income inequality. Seattle City Council Member Kshama Sawant used the recent closure of the Alaska Way Viaduct to introduce her vision of free transit for everyone. In March, Luxembourg will become the first country to make transit free entirely, but the scheme is already at work in cities like Tallinn, Estonia and Dunkirk, France. To date, there are 97 (mostly small) cities and towns around the world with fully fare-free public transit. Enchanted by the possibilities, several US transit advocacy groups are calling for the elimination of fares.

But what does the research tell us? Should free transit be the end goal for advocates and policy-makers?

Transit agencies need money to run service, and major transit agencies in the US rely on fares for a substantial portion of their operating revenue. In New York, the $4.5 billion the MTA receives in annual fare revenue comprises 50% of its operating budget. At the Chicago CTA, that percentage is 40%, and in San Franciso BART’s is 62%. Eliminating fares means that revenue would need to come from somewhere else, and the federal government only provides very small transit agencies with operating assistance. Funding transit operations entirely by other measures (such as a tax on businesses) would be a heavy political lift, and hasn’t been done in the US.

But let’s say agencies did find other ways to subsidize operations. What effect would free transit have on ridership? Around the world, the verdict is still out on whether going fare free substantially changes people’s travel choices. In Dunkirk, population 100,000, ridership increased by 85% immediately after the introduction of fare-free transit. But in Tallinn, population 426,000, ridership has only increased by 3% in the five years since transit was made free.

Ridership increasing is the desired outcome, but without sufficient revenue to increase service in response to new demand, agencies run the risk that riders will be turned off by delays and overcrowding. In fact, that’s what happened in several US cities who tried free transit but abandoned the projects after they created more problems than they solved.

When researching our forthcoming report, Who’s on Board 2019, we surveyed 1700 transit riders in seven different cities across the US. What we heard is that most low-income bus riders rate lowering fares as less important than improving the quality of the service. This suggests that if a transit agency had to choose between devoting funds to reducing fares or to maintaining or improving service, most riders would prefer the latter. The idea of making transit “free” turns out to be less appealing to the public than making improvements to transit.

What are superior and sustainable ways to move the needle on ridership? Making transit fast, frequent, and reliable. In just a few short years, Seattle has nearly tripled the number of people able to walk to frequent transit, and ridership continues to climb. Ridership has also been gaining in San Francisco, where SFMTA has an ongoing program to speed up buses. Cities like Austin, Richmond, and Columbus are redesigning their bus networks to better connect people to jobs, and seeing ridership growth as a result.

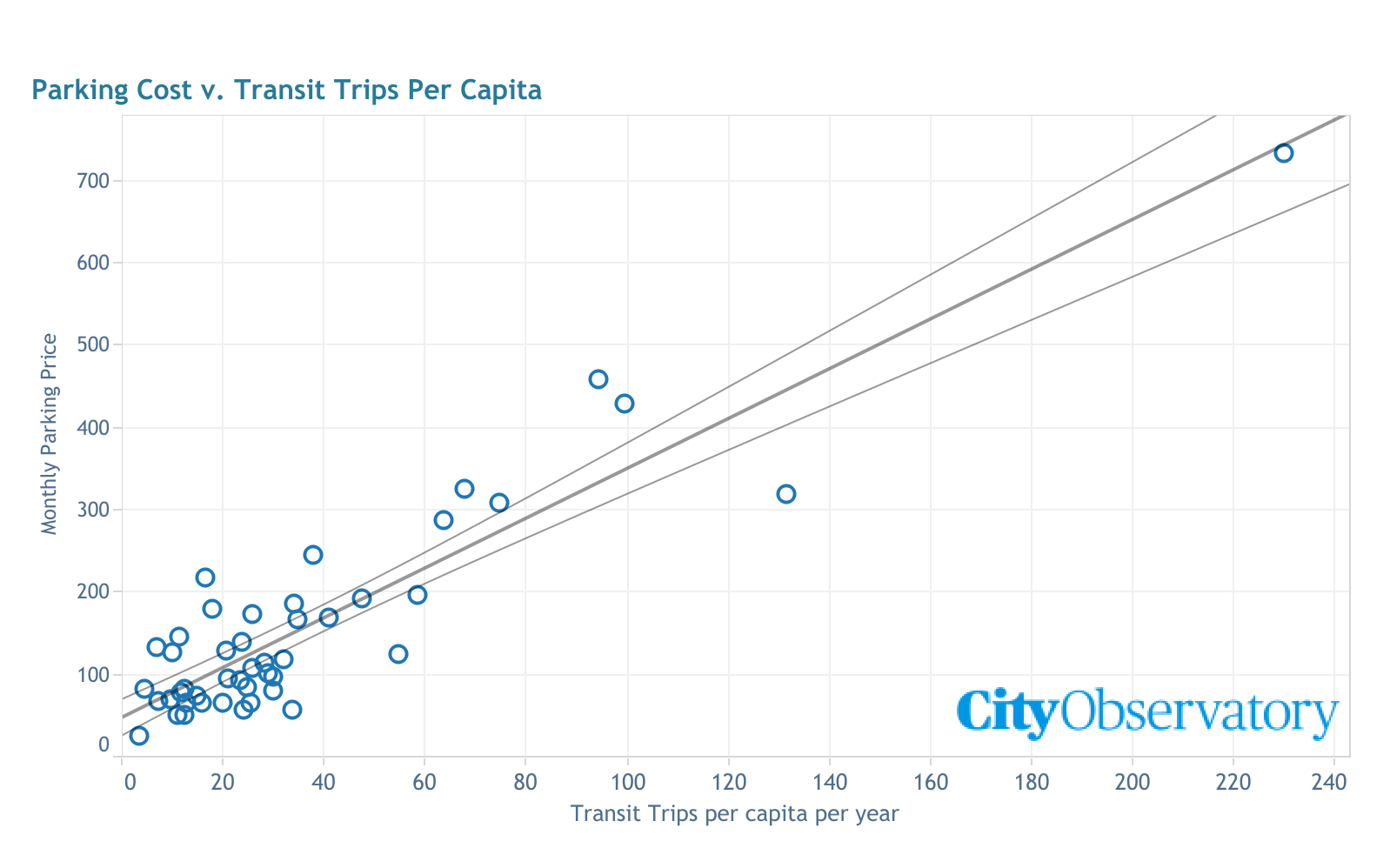

Raising the cost of driving also has a tremendous effect on transit ridership. Public transit ridership went up by 18% in London after the city enacted a toll on drivers entering the center city. And across the US, the cost of parking in central business districts tracks well with transit ridership, suggesting more people are willing to take transit if the price of parking goes up.

Shifting cultural norms around taking transit can also make a difference. Large numbers of middle class people riding transit in cities can change the abiding perception that transit is for poor people, and boost ridership overall. Thanks to Washington State’s 1991 Commute Trip Reduction Law, which makes large employers responsible for reducing traffic congestion, 83% of employers in Downtown Seattle subsidize their employees transit passes. Employer-funded passes provide transit agencies with a consistent source of revenue, and ensure that transit riders represent a cross section of society. In Los Angeles, where transit ridership has been plummeting, a recent program at NBCUniversal offered employees subsidized transit passes, provided incentives for taking transit, and matched “transit curious” riders up with experienced transit riders. Within six months, the percentage of people taking transit to work at NBC went from 19% to 59%.

Of course, ridership isn’t transit’s only goal – ensuring access is also critical. Fortunately there are ways to make transit affordable without disrupting revenue streams entirely. Seattle and Portland have both developed successful discounted fare programs for riders below the federal poverty line. These programs can be funded by increasing the price of monthly passes (which are often dramatically discounted) or through partnerships with municipalities. Austin’s transit agency Capital Metro recently made transit free for children under 18, and there’s no reason that transit agencies shouldn’t do this across the board. TransitCenter research indicates that people form opinions about transit when they’re young, and early exposure can lead to long term loyalty.

LA Metro CEO Phil Washington recently made waves when he proposed to “save mankind” by making transit free by enacting congestion pricing on roads across Los Angeles. According to Washington, the $12 billion or so generated from congestion pricing could be used to fund transit investments “so major that buses could run every 90 seconds on many streets,” among others. The proposal is in its infancy, and faces a bewildering number of obstacles. To date, no US city has enacted congestion pricing, and car dependent Los Angeles seems an unlikely first victory. But if free fares are appropriate at any big transit agency, it’s probably at LA Metro. Metro’s farebox recovery ratio is a mere 17%, and the average annual income of its riders is $17,000. The agency could technically get by without fare revenue, but the scheme would only work if massive funding was injected into improving current service, rather than into splashy, long-term rail projects. Success would also require repurposing traffic and parking lanes on city streets so that buses could move freely.

Free transit makes for a terrific news hook. But the only way to see the full benefits of transit – like improved air quality, less congestion, and more vibrant cities is for people to actually start riding transit in substantial numbers. To this end, agencies should immediately make transit more accessible by offering discounts to riders who need them the most. More employers should be compelled, whether through penalty or incentive, to subsidize transit passes. But what advocates and policymakers should actually be focusing on is a multi-pronged approach to make driving less attractive, and undoing policies that make driving feel free. Cities and transit agencies should work together to raise parking rates and replace swaths of curbside parking with transit priority streets. And while congestion pricing isn’t feasible for most US cities, large metro areas with robust transit networks should start laying the groundwork. Funneling money from these pursuits directly into improving transit will yield precisely the type of benefits sought by proponents of free transit.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

Transit advocates, organizers, and riders are calling on local and state agencies along with the USDOT to advance projects designed to improve the mobility of Black and Brown individuals at a time when there is unprecedented funding and an equitable framework to transform transportation infrastructure, support the climate, and right historic injustices.

Read More