It’s been just over a year since Everett – a small city outside of Boston – launched its peak-hour bus lane on Broadway. Results show that the one mile stretch is cutting trip times by 20-30% and the city is now working on bus stop consolidation, transit signal priority, and more bus lanes. Until this pilot project, there had been little action to improve bus speeds and reliability in the Boston region. But in the wake of Everett’s investment in several hundred traffic cones and no small amount of political capital, Cambridge began working on bus priority treatments last summer. And after years of talk, the City of Boston finally in December “tested” a one-day pop-up lane of its own (spoiler alert – it worked!) on a chronically jammed high ridership route, with further “tests” pending. Our graduate fellow, Rosalie Ray, sat down with Everett’s Transportation Planner Jay Monty to learn more about how his city took the lead on transit.

How did the Broadway bus lane come about?

We’re the only city that borders downtown Boston that doesn’t have rapid transit. We also have only a couple of roadway connections that actually get into Boston because there’s a body of water between Everett and Boston. Many of our 50,000 residents are low-income, and we have very high transit ridership in our city.

Recognizing this, the city commissioned MassDOT to do a transit study, the Everett Transit Action Plan. We looked at a whole host of project options, ranging from low-hanging fruit to the big infrastructure ideas, extending BRT service, extending rail service of some sort. The bus lanes were the low-hanging fruit option and something we believed we could do within a 1-3 year time frame. We had a couple of roadways that had some room – if we could take parking out, we could fit a bus lane. Our mayor and city staff were eager to do something immediately after that study was published, so we had a meeting with MBTA bus operations folks. At that point it was really just them telling us, “Ok, we need a lane width of 11 feet, and if you give it to us, we’ll use it.”

As we got into discussions with them, one of the big questions for me was “If we’re going to put all this work into speeding up bus service, we have to go farther—we need to add capacity. At rush-hour, buses are at crush loads and the T has said for a long time that they don’t have the ability to add buses. So my question became, if we sped up buses enough, could we gain an extra trip using the same number of buses? The T was open to that, but said that to adjust the spring schedule (which is when we were looking to do a pilot), they’d need data by December.

Our response was, well, “What if we just put out cones for a week? How many days do you need to collect data and see how much time you could save by getting buses out of the general traffic lane?” So we agreed to a week, and put the cones out the first week in December. On the third day it was going so well the mayor said “Don’t stop.” And we went from there.

Our Department of Public Works folks have been working overtime for the better part of the year putting cones out; we have a couple of parking enforcement officers out there every day. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks ago that we actually had the paint down. It sounds simple and it was simple. It was really the T saying “here’s what we need to run a bus, and if you give it to us, we’ll put the bus in it.”

What data did you need to argue for the bus lane’s continued existence?

I would look at any of the improvements we’re doing and say, well these should happen regardless of data. At this moment we’re viewing these improvements simply as best practice. We know that 10,000 people a day ride the bus down Broadway, and that it’s half the mode share during certain times of day. We don’t need much more than that to say that justifies taking parking and prioritizing transit. We had a little bit of parking data for the downtown stretch [of Broadway], which is the busiest in terms of parking, and we knew that even in the busiest spots parking was underutilized pretty substantially.

Often, building bus lanes and taking parking leads to considerable public outcry. What outreach did you do and what was most successful?

The way I look at it, the best public outreach comes from actually doing it, not talking about it. Because the transit study was so close time-wise to the pilot [the study finished in October 2016 and the pilot was in early December], we really didn’t do any public outreach other than hand out flyers to people saying there wouldn’t be any parking next week. If we’d had a community meeting and told folks we were going to take parking on one side of the road for five hours every day, that probably wouldn’t have gone over so well. Going and doing it, and being honest that we were just trying it, that makes it real. Whatever people’s fears were, they have to get checked with reality and I think that enabled us to make this successful. Staff from the T and MassDOT were on the buses that very first week doing surveys with folks. We also used the city Facebook page, 311, and local newspapers to ask “What do you think? How’s it going?” We got a few complaints but for the most part it was fine.

The other thing with taking parking is that most cities sweep streets, and most of the major corridors that go through downtown get swept at night. The idea of taking all the parking during the early morning or overnight—we were already doing it on the corridors we were talking about for these buses. If you’re taking parking already once or twice a week, how much harder is it really to do it every day? You’ve already proven that you can find places for the cars during that time period.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

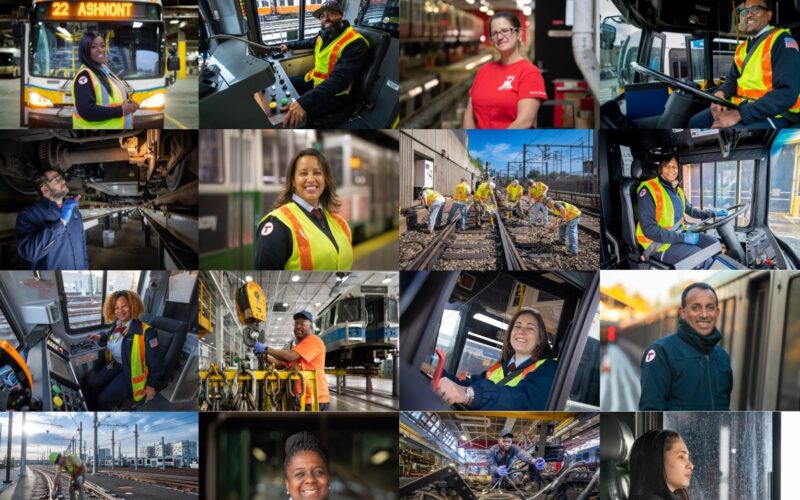

Read More MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and its union, Carmen’s Local 589, reached a historic agreement to increase bus operators' starting wages from $22.21 to $30 an hour, shifting MBTA operators from the lowest paid to the highest paid in the transportation industry.

Read More