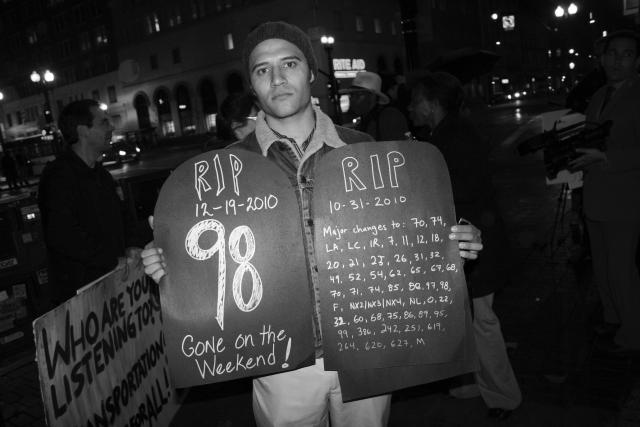

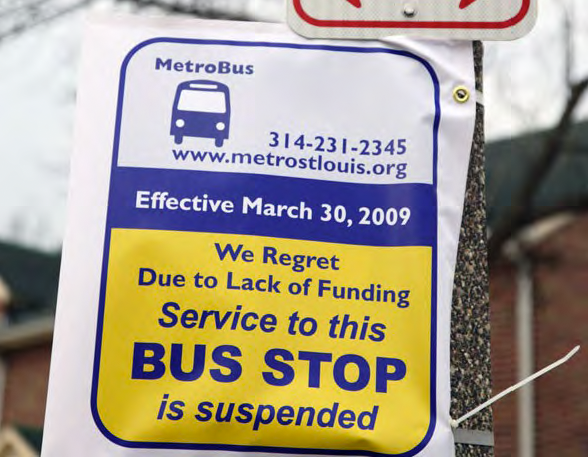

2009 service cuts affect riders in St. Louis Image source: Transportation For America: Stranded at the Station

Unlike death and taxes, funding for transit is never guaranteed. However, the arrival of the Trump administration brings unprecedented levels of uncertainty to federal transportation funding programs. His trillion dollar “infrastructure proposal,” if a serious policy at all, has indicated zero support for transit. Moreover, Trump has threatened to cut off all U.S. funding for “sanctuary cities” that fail to comply with federal immigration enforcement. While the legality of such a maneuver remains dubious, cities like New York have already begun preparing review of worst cases, to avoid being caught unprepared by radical federal policy shifts.

Concern for U.S. transit funding extends beyond the vague references in Trump campaign or inaugural material. Heritage Foundation positions, which label transit a local concern, are being consulted by the new administration. The GOP policy platform itself also calls for elimination of the Federal Transit Administration, and Republicans in Congress have taken repeated aim at the FTA, so far without major impact. At her confirmation hearing last week, Elaine Chao revealed little about administration priorities beyond refusing to guarantee funding for transit construction projects already in the works.

What options might transit agencies have in a volatile or punitive funding climate? How should they react beyond initiating the transit “death spiral” of simultaneously cutting service and maintenance and raising fares? A period worth analyzing is how transit agencies weathered California’s extreme budget crisis during the Great Recession, when the state eliminated all operating aid for transit. While the federal government’s contributions to transit are primarily for capital expenditures, there are still lessons to be gleaned from transit systems’ experience in this period. Transit agencies would do well to forearm themselves with the kinds of scrappy survival strategies that helped fill some of the worst gaps.

Governor Schwarzenegger’s 2009-2010 budget eliminated the State Transit Assistance (STA) program, the only ongoing source of state funding for the day-to-day operations of public transit. At the time, the STA accounted for as much as 70 percent of the total budget for some of the state’s transit providers, so its elimination quickly precipitated a combination of service cuts and fare hikes across the state. No agency was spared: L.A. Metro was forced to cut as much as 160,000 hours of bus service, despite the fact that voters had just approved Measure R to expand transit. Sacramento Regional Transit District cut service by 10%. According to Stranded at the Station, a 2009 Transportation for America report, many agencies were forced to eliminate lifeline services for the most vulnerable riders.

2009 service cuts affecting AC Transit Riders in CA

Some agencies found ways to lessen these blows. The San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency, second largest in the state, faced a $129 million dollar budget shortfall upon STA’s elimination. However, state law enabled so-called “Congestion Management Agencies” (typically the transit agency in a given municipality) to put a $10 vehicle registration fee before voters to fund transportation projects. San Francisco County approved the fee in 2010 — today it generates around $55 million a year for transit operations. Additionally, the agency negotiated with labor unions for concessions, located “lifeline” funding grants and ultimately laid off a small percentage of its workforce.

On a smaller scale, The San Joaquin Regional Transit District, which operates buses in Stockton also faced a crippling deficit. In response, the agency developed a scoring system to preserve its most productive routes when imposing service cuts, and found ways to increase system-wide efficiency. It also cut personnel to balance its reduced budget. Additionally, it aggressively sought discretionary grants to cover the cost of capital projects, allowing it to shift other capital funds to cover operations. Some of this came in the form of grants from the FTA, others from the state. Thanks to its multi-faceted response, SJRTD survived relatively unscathed and currently has the 20th highest ridership in the state.

Litigation restored the STA in 2010, but even so, the local share of transportation revenues has steadily increased in California since 2011. Can transit agencies across America execute a similar transition for capital budgets if faced with severe cuts? Capital disinvestment isn’t pretty – do a Google image search for “NYC subway 1981,” read about the recent history and performance of Boston’s MBTA, or take a look at Washington D.C.’s plan to restrict rail service so emergency repairs can take place.

New York City subway in 1981

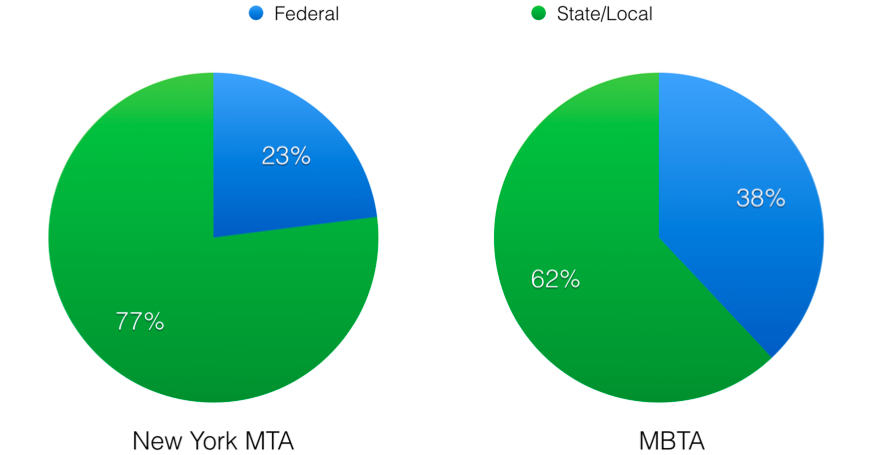

Many municipalities and regions have developed the means and traditions to raise their own funding for transit expansion and upkeep. Cities as wide-ranging as Raleigh, Atlanta and Indianapolis — in addition to the well-known Los Angeles and Seattle examples — decided to do just that last November. The largest transit system in the country, New York’s MTA, relies heavily on local and state revenue sources for capital investment, via a program authorized by the state legislature encompassing a myriad of taxes, and incorporates funding from the City of New York.

NYC MTA’s budget breakdown vs. Boston’s MBTA

That said, the abrupt loss of a large share of anticipated capital funding would cause budgetary chaos and job losses in major rebuilding efforts and expansion projects in the pipeline, even in our largest cities. Many small, suburban and rural agencies are also more heavily dependent on federal aid than large transit systems. And systems whose states or metro areas have done a poor job diversifying capital funding away from federal reliance, such as Boston’s MBTA, or have a special funding relationship with the federal government like the Washington Metro, would be in especially deep trouble. It’s possible the transit ballot initiative, relatively unknown in the northeast, could become a regular policy feature across America’s metropolitan areas unless governors and state legislatures prepare to lead directly to keep our cities moving, efficient and liveable.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

To create the “state-of-the-art bus transit system” of his campaign platform, Mayor Adams will have to both expand the quantity and improve the quality of bus lanes. We recommend these strategies to get it done.

Read More