It’s been more than thirty years since an American city opened a new subway system, but transit agencies haven’t stopped investing in rail. From Houston to Phoenix and Sacramento to Seattle, light rail lines are opening or expanding at a steady clip. In addition, mixed-traffic streetcar lines—which run shorter routes and do so more slowly than light rail—are opening or in the planning stages in an equally broad array of cities. Despite some lines (both light rail and streetcar) on which ridership remains stubbornly low, overall ridership on these modes has increased 46 percent in the last ten years.

Across the Atlantic, however, the Paris regional transit agency has embarked on a street-level rail expansion effort far surpassing that of any city here.

The Paris tramways have proven exceptional not just because there are so many of them (nine, with more in the planning and construction phases), but also because they are so popular. Ridership is 900,000 per day, which is five times greater than America’s busiest light-rail system (Boston’s Green Line) and greater than any subway system in the U.S. except New York.

All this is taking place on a network whose first line opened just 24 years ago and whose entire existence many visitors to Paris might not even be aware of, given that the routes are in the less touristy parts of the region.

Any city in the U.S. building or planning a street-level rail line would love for it to have just a fraction of the Paris trams’ popularity. Supporters of the Brooklyn-Queens streetcar line proposed in New York, for example, dismiss low-performing American streetcars and say the line will be more like those in Europe. So it’s worth examining what exactly has made the Paris trams so successful.

They create seamless connections

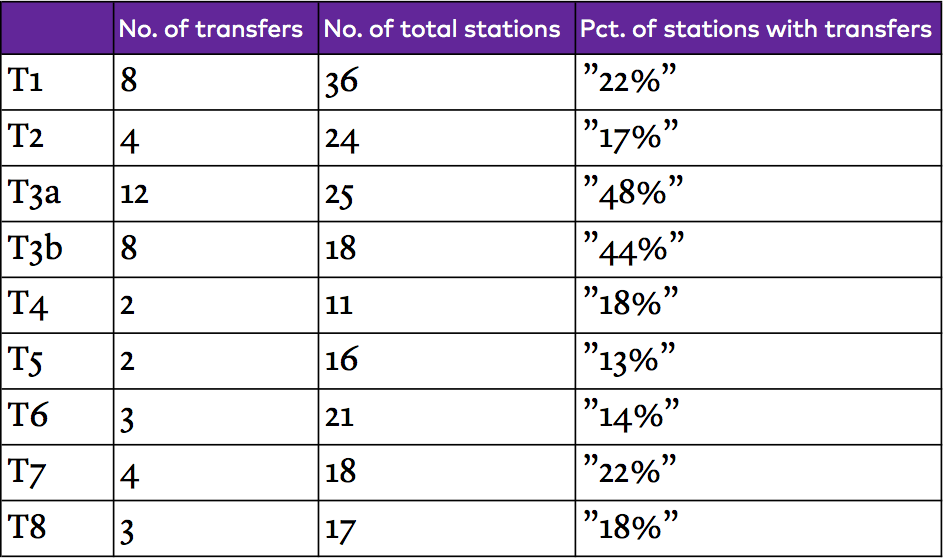

It takes just a few seconds looking at the RATP map to see why the Paris trams are so useful. In Paris’s hub-and-spoke transit network, they are the rim of the wheel, connecting the ends of Metro and RER lines in far-flung parts of the region. All nine lines offer at least two stations that connect to other modes of transit. Some offer many more:

It’s not just, as the map implies, that the tram lines travel near other transit stations. In most instances, the streets and stations are designed to make the connection as smooth as possible. Here, for example, is the T1 tram where it meets the M7 Metro line at the La Courneuve station in Aubervilliers. The stairs to the underground Metro platform deposit riders right at the tram:

Even commuter rail stations don’t present an obstacle to tram transfers. Here again the T1, this time at the Noisy-le-Sec rail station on the RER:

Google Street View

Google Street ViewThe ability of the trams to link existing transit is not a happy coincidence, but rather an explicit goal of the network’s planners. According to Sandrine Gourlet, a STIF deputy director who spoke to Le Figaro about the trams back in 2012, the agency calculated that forcing customers to make transfers that take longer than two minutes produces a ridership drop of 10 percent.

They are part of bigger street redesigns

The Paris trams haven’t just brought about street redesigns around the station areas. Rather than trying to jam the lines into existing traffic patterns and streetscapes (as U.S. streetcar lines tend to do), the trams run overwhelmingly in rights of way constructed to be completely clear of motor vehicle traffic and almost always accompanied by improvements to the pedestrian environment, traffic calming measures, and other infrastructure. Note the changes in these “before” and “after” images of the Boulevard Davout, on the T3b tram line at the far eastern edge of Paris proper.

Google Street View

The tram doesn’t merely get its own right of way (though that’s critical, given how many street-level rail projects in the U.S. ignore the idea). In addition, the distance pedestrians must walk to cross southbound traffic was cut in half. The crosswalk was brought away from the intersection allowing for safer pedestrian travel, and the streetlight at the corner was moved, eliminating an obstacle for crowds of people exiting the Metro station that lies beneath the intersection.

They don’t charge riders extra

In Paris, the vast majority of people who use the core transit system can ride the trams at no additional cost. Regular commuters tend to have the region’s touch-and-go card, known as Navigo, for which they can purchase monthly or annual passes valid for a certain number of zones. If a tram line is located in those zones, they can use the same Navigo card. Infrequent riders with paper tickets can also use the trams, either at the start of their trip or if they transfer to a tram within 90 minutes of first entering the system.

A notable exception: people with Navigo cards without the requisite number of zones cannot use those cards on a tram outside those zones. They can, however, always buy a paper ticket.

They avoid traffic

It always merits a reminder: street-level trains usually aren’t worthwhile investments if they have to compete with cars for space. Mixed-traffic streetcar lines are slower, less reliable, and represent little or no upgrade relative to a bus. Yet such designs are stubbornly prevalent in the U.S. for a simple reason: elected officials don’t want the hassle of confronting motorists.

In the Paris region, on the other hand, there seems to be recognition that any significant street-level transit improvement probably has to come at the expense of cars—and the tram lines are designed accordingly. Take, for example, this street at the terminus of the T5 in Saint-Denis:

Google Street View

Or on the other side of the city in Châtillon, where a street running under an office building was replaced entirely:

Google Street View

It should be noted that the Paris trams are not entirely separated from cars. Small sections where exclusive right-of-way would have been extremely difficult to build, such as on the bridge carrying the T1 over the Seine, allow the two to mix. These areas, however, are kept to a minimum and represent a tiny proportion of the tram system.

They run all the time

The Paris trams don’t literally run all the time. Unlike New York’s subway, they and the rest of the RATP close overnight for a few hours.

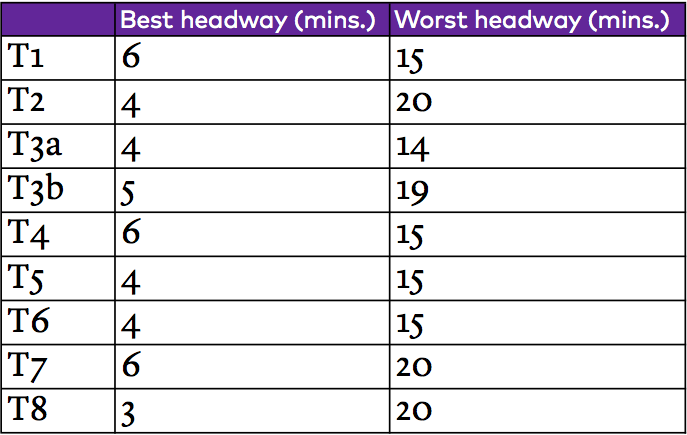

During the vast majority of the week, however, tram riders in the Paris region wait less time for a tram than many subway riders do in the United States. The RATP maintains a level of service for the tram system that is very high by global standards (and remember, this is a system that is ancillary to the Metro and the RER regional rail lines). According to the most recently published schedules, here are the best and worst headways for each line:

Note that many of these schedules include the RATP’s August service plan, when the agency typically runs fewer trains due to the large number of Parisians who leave the city for vacation. Even in August on an early Sunday morning, there is no line in the system where a rider must wait more than 20 minutes. During midweek rush hour, the worst headway is six minutes.

The RATP’s commitment to low headways isn’t just worthwhile in and of itself—without it, the trams would not serve their purpose as outer-ring links in the region’s transit system. It is what makes the system work as an alternative to transferring at one of the Metro’s large central hubs, then traveling outward again to a final destination.

This same principle of creating a network of frequent service that permits truly regional access has informed some of the best recent transit reforms in the U.S., including Houston’s reimagined bus system. But too many U.S. streetcars, whether in operation or being planned, don’t heed Paris’s example—on this point or on any of the others.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

To create the “state-of-the-art bus transit system” of his campaign platform, Mayor Adams will have to both expand the quantity and improve the quality of bus lanes. We recommend these strategies to get it done.

Read More