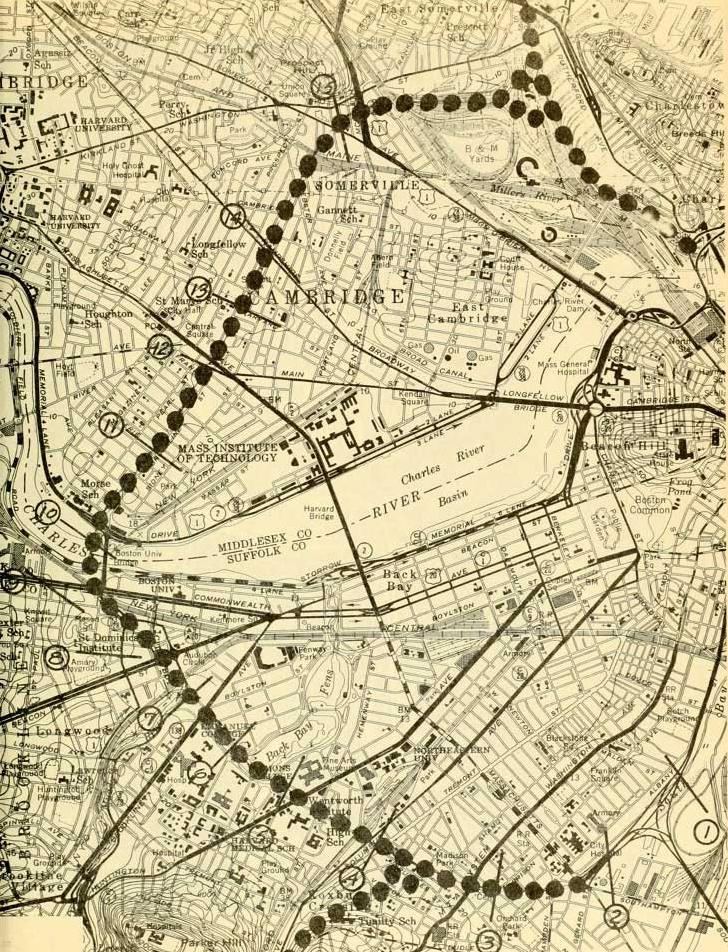

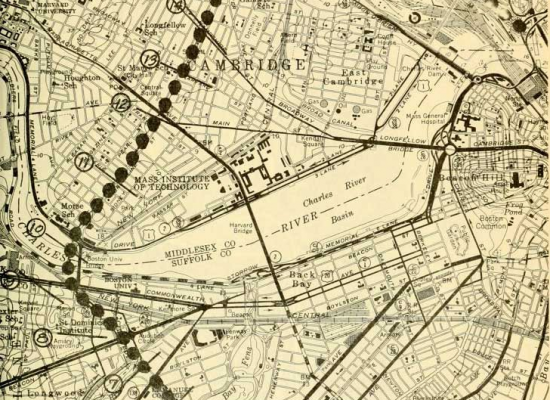

A proposed alignment of the Inner Belt. (Source: Boston Dept. of Public Works, Right of Way Bureau, 1965)

A proposed alignment of the Inner Belt highway. (Source: Boston Dept. of Public Works, Right of Way Bureau, 1965.)

This post has been updated to reflect the existence of the Logan Express service proposed in Sargent’s speech.

In 1970, in response to protests over highway plans that would involve government seizure of land, homes, and businesses for highway construction, Massachusetts Governor Francis W. Sargent took the unusual step of declaring a moratorium on highway construction inside Route 128, Boston’s suburban beltway. In its place, Sargent called for a comprehensive multimodal study of the region’s transportation needs.

The study concluded two years later, and in a speech to the public on November 30, 1972, Sargent announced the multibillion-dollar investment plan that was its result. The proposed Inner Belt highway, which would have ripped through the urban fabric of Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville, had been shelved. Instead, Sargent declared a relaunch of the state’s commitment to public transportation in the Boston area, as well as the construction of select, strategic highway links less intrusive than the Inner Belt. The entire address merits a listen.

Over 40 years later, Sargent’s speech stands out for the clarity, honesty, and prescience in its purpose and its language—qualities lacking in the transportation speeches many state-level chief executives give:

You, your families, your neighbors have become caught in a system that has fouled our air, ravaged our cities, choked our economy, and frustrated every single one of us…We have been caught in a vicious cycle. More cars meant more highways, which meant more traffic jams; more traffic jams meant the need for more highways, which meant more traffic jams and the need for superhighways…The side effect: billions of dollars spent and more and more cities torn apart, more and more families uprooted and displaced. Worst of all: failure to solve the problem that started it all.

Although similar rhetoric occasionally surfaces among transportation officials today, it rarely leads to actual changes in policy or practice. U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx, for example, has spoken out against “highways and railways and airports that literally carved up communities.” But the legislation that guides most USDOT spending continues to do just that, helping fund urban highway expansions in places like Birmingham and Little Rock. Many city and state leaders today also labor under the belief that they can create good transit systems and highway systems in equal measure, which only reinforces dependence on cars as a result of the new roadway and parking capacity.

Sargent, in contrast, announced a clear set of investment decisions that have had a major impact on Boston’s present-day transportation and urban design—though some took much longer to complete than he anticipated. In addition to the earlier Inner Belt cancellation, which preserved some of the region’s most pleasant and walkable neighborhoods, Sargent proposed:

- The conversion of the Southwest Corridor, slated to become an expressway, into a pair of sunken subway and commuter-rail lines with a linear park on top. The decision eliminated the need for additional seizure of property in working-class neighborhoods and allowed for the eventual removal of the Washington Street Elevated subway line.

- The Northwest Extension of the subway line ending at Harvard Square, which resulted in the construction of new stations in Cambridge and Somerville at Porter Square, Davis Square, and Alewife.

- A freeze on the creation of new public parking in downtown Boston.

- State aid to smaller transit systems in rural areas.

- The burial of the Central Artery highway in downtown Boston and construction of a new underwater tunnel to Logan Airport, both of which were completed decades later as part of the “Big Dig.”

- Suburban park-and-ride lots for airport-bound travelers.

Not all of the projects in Sargent’s vision came to fruition. Notably the idea of a rail tunnel connecting North Station and South Station, then just a seed of an idea, is still a contentious issue in Massachusetts politics as of this week.

Nonetheless, in an era when many of the oldest transit systems in America suffered from severe neglect, Sargent dared suggest that there was nothing inherently wrong with public transportation. Rather, he said, “most mass transit is no good today because it was ignored yesterday.”

“Shall we build more expressways through cities? Shall we forge new chains to shackle us to the mistakes of the past?” asked Sargent. “No. We will not repeat history. We shall learn from it.”

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

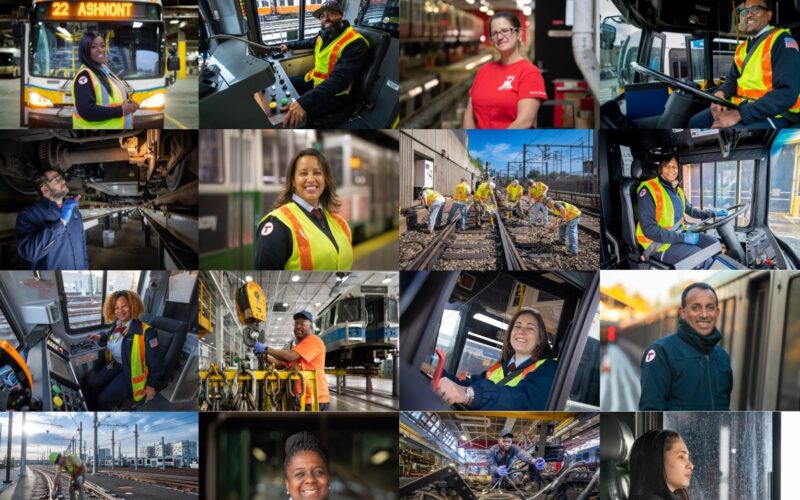

MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and its union, Carmen’s Local 589, reached a historic agreement to increase bus operators' starting wages from $22.21 to $30 an hour, shifting MBTA operators from the lowest paid to the highest paid in the transportation industry.

Read More