Slumping ridership doesn't mean transit riders are gone for good -- but they are riding less. To win them back, cities and transit agencies must make a concerted effort to improve service.

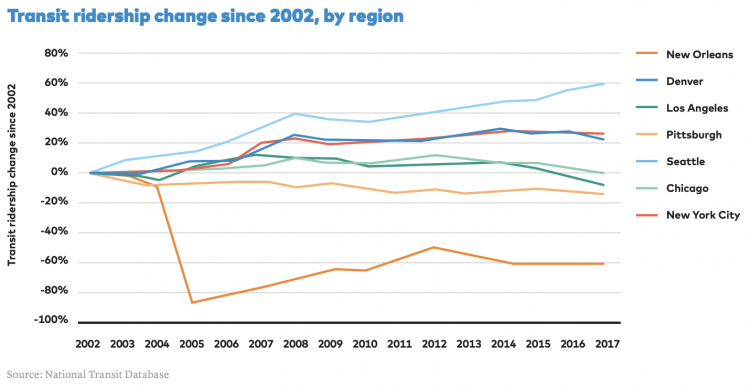

Excuses abound for falling transit ridership in American cities. Transit agencies have blamed the growth of Uber and Lyft, an expanding economy, falling gas prices, and cheap car loans for recent declines in bus and rail ridership. These explanations describe real forces buffeting the nation’s transit systems, but they don’t tell the full story.Even against strong headwinds, transit ridership is on the rise in some cities. To understand how agencies can retain riders and gain new ones, you need to talk to people who ride transit about what informs their travel decisions.

For our new report, Who’s on Board 2019, TransitCenter surveyed 1,700 transit riders in seven American cities. We asked: How have you changed your transit riding habits over the past two years, and why? The answers illuminate why transit use has fallen and how transit agencies can win back riders.

People are cutting back on transit, not abandoning it

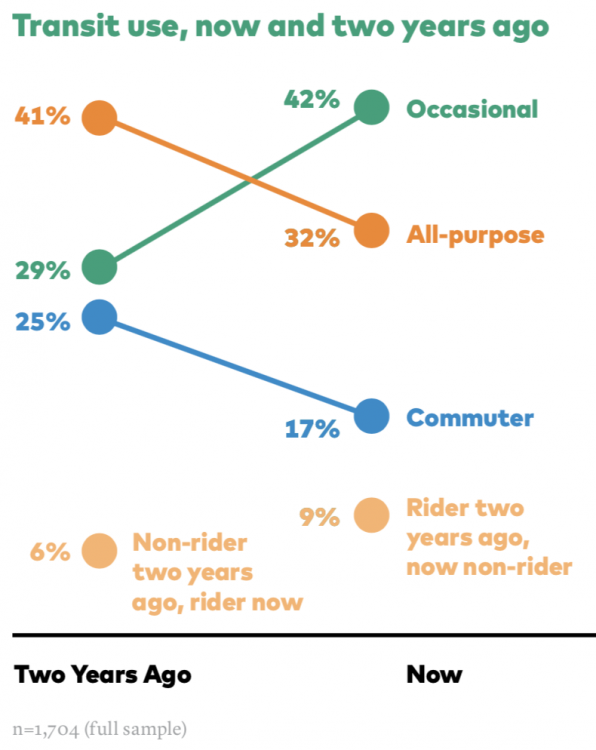

For the most part, people are riding transit less than they did two years ago, not cutting transit out of their lives altogether. The number of “all-purpose” riders who use transit on a daily basis and the number of transit commuters are diminishing, while the number of occasional riders who take transit once a week or so is on the rise.

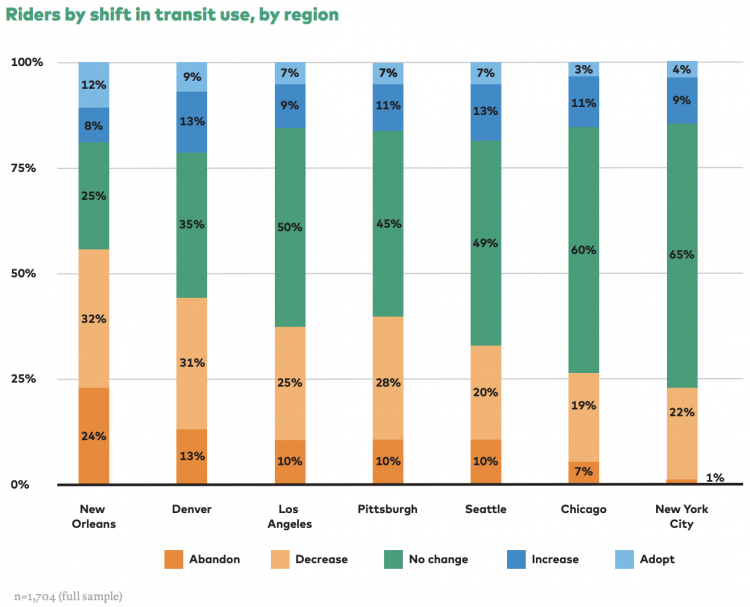

Even in New Orleans, where the percentage of people who stopped riding transit was highest, far more people reduced their transit usage than eliminated it:

The fact that the vast majority of riders have not abandoned the transit habit suggests that agencies have an opportunity to regain ridership by offering these riders more appealing service.

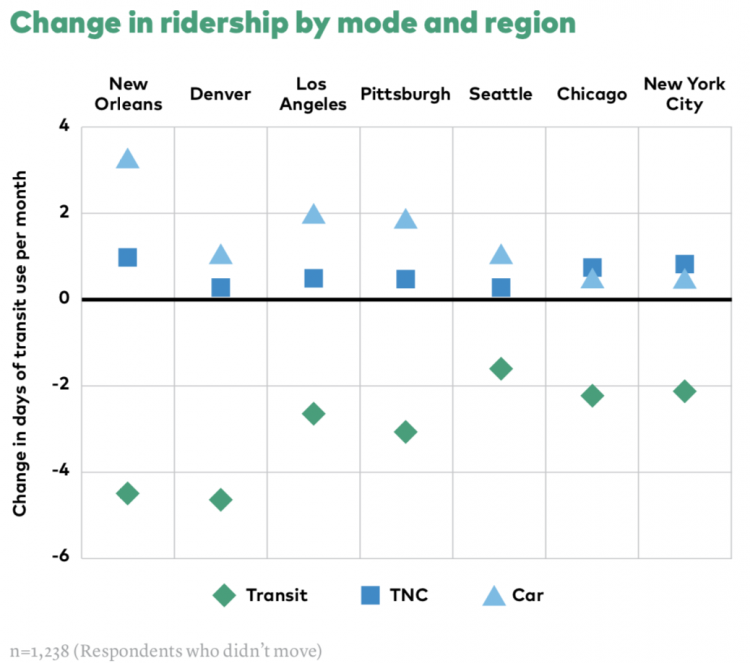

In most cities, private cars — not Uber and Lyft — are the main competition for transit

In five of the seven cities we surveyed, respondents replaced transit trips mostly by driving their own cars, not hailing an Uber or Lyft.

This is not to say that tailored policies to regulate Uber and Lyft are unwarranted — in dense, big cities like New York and Chicago, where we did find that transit is losing ground to these services more than private cars, a response is especially necessary — but any policy that targets Uber and Lyft while failing to make transit more competitive with private automobiles won’t make much impact. Cities and transit agencies should be thinking on the level of systemwide plans for transit-only lanes, all-door boarding, and more frequent service, not just a surcharge on ride-hailing trips.

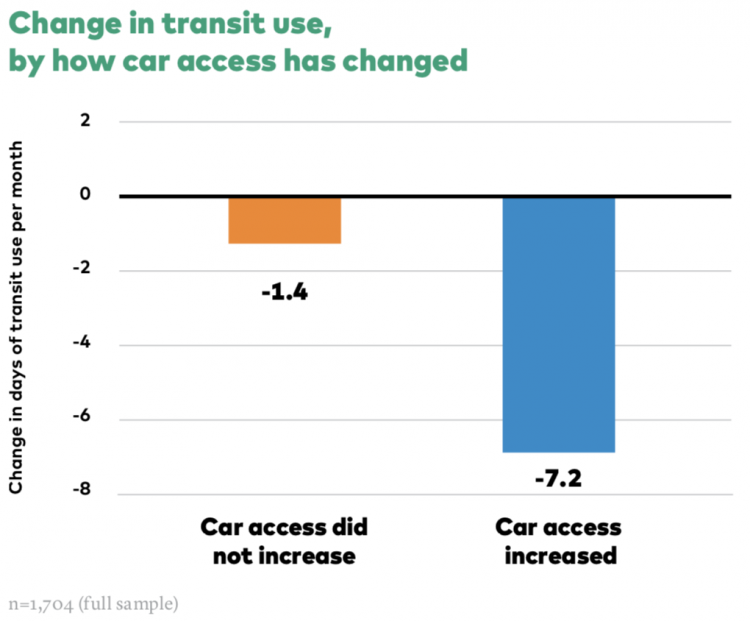

Respondents who acquired a car during the two-year survey period cut their transit use five times more than people whose car access stayed the same or declined. And with the expansion of cheap credit for car loans, vehicle ownership is on the rise. Of Who’s on Board respondents, 54% now have full access to a private car, compared to 43% two years ago.

While this may seem like a story of increasing transportation choice, in many respects it reflects the paucity of good choices Americans face. People are driving more because in places built for cars, transit isn’t meeting their needs. Even in transit-rich cities, poor service quality is pushing people into cars: Riders in New York and Chicago were disproportionately likely to cite worse transit service as a reason for driving more. Nationwide, large numbers of people are opting to buy cars they can’t afford. The Washington Post reports that the number of Americans at least three months behind on their car payments is at a record high.

Low-income people are moving farther from good transit

When people move, their access to transit is likely to change, and so are their transit riding habits. More than two-thirds of respondents who moved to a different home reported at least some shift in transit ridership.

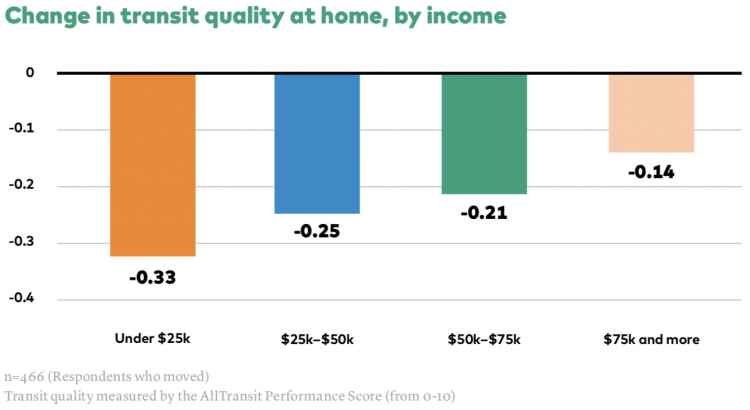

Low-income people use transit most often, but according to our survey they have had to move farther from quality transit than people with higher incomes. Of all our respondents, 27 percent moved in the past two years, and among these movers, people with household incomes below $25,000 endured a marked decrease in transit quality by their residence as a result. The typical change was akin to moving from Washington, DC, to Baltimore, Maryland, or from Times Square to Astoria, Queens.

High-income respondents (households making $75,000 or more annually) who moved did not experience as big a loss in transit quality. The difference in their typical transition was like going from Times Square to the East Village.

Smart policy and political leadership can win back transit riders

There is nothing inevitable about falling transit ridership. More people will choose to ride transit if the service delivers what they want. And according to our survey, transit riders want frequent, reliable, and safe service. Transit agencies and city governments have the capability to make this happen.

Transit agencies can adopt all-door boarding to speed buses, use data-driven dispatching to improve bus reliability, and build shelters to give riders a dignified experience waiting for the bus. Running more service on high-ridership routes or redesigning outdated bus networks for current travel needs will make transit more convenient for many riders. In cities including Seattle and Austin, these methods have made bus service more competitive with driving, and ridership is going up.

Working together, local governments and transit agencies can roll out bus lanes and transit signal priority to prioritize transit on city streets. When Everett, Massachusetts, converted curbside parking to a bus lane, travel times dropped by up to eight minutes along the corridor.

Transit policy also must be crafted in coordination with housing and development policy. Clustering affordable housing in transit-rich areas ensures that people who ride transit the most can afford to live near quality service. Seattle’s Sound Transit sells its land at a discount for low-income housing development, and Los Angeles Metro offers low-interest loans to low-income housing developers. Agencies can also target underserved areas that reach a requisite density and predicted ridership level for new transit service: Portland’s TriMet launched two new bus routes that connect the poorest communities in the city to an industrial job center.

Public officials can’t throw up their hands and claim there’s nothing they can do about falling transit ridership. The only responsible course is continuous, rider-focused service improvement and public policy that provides equitable access to quality transit.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Thanks to Riders' Alliance successful #6MinuteService campaign, New York City subway riders will enjoy more frequent service on nights and weekends, starting this summer. In this post, we chronicle the group's winning strategies and tactics.

Read More