In many years, Vermont “flexes” enough highway dollars to effectively double its federal transit funding

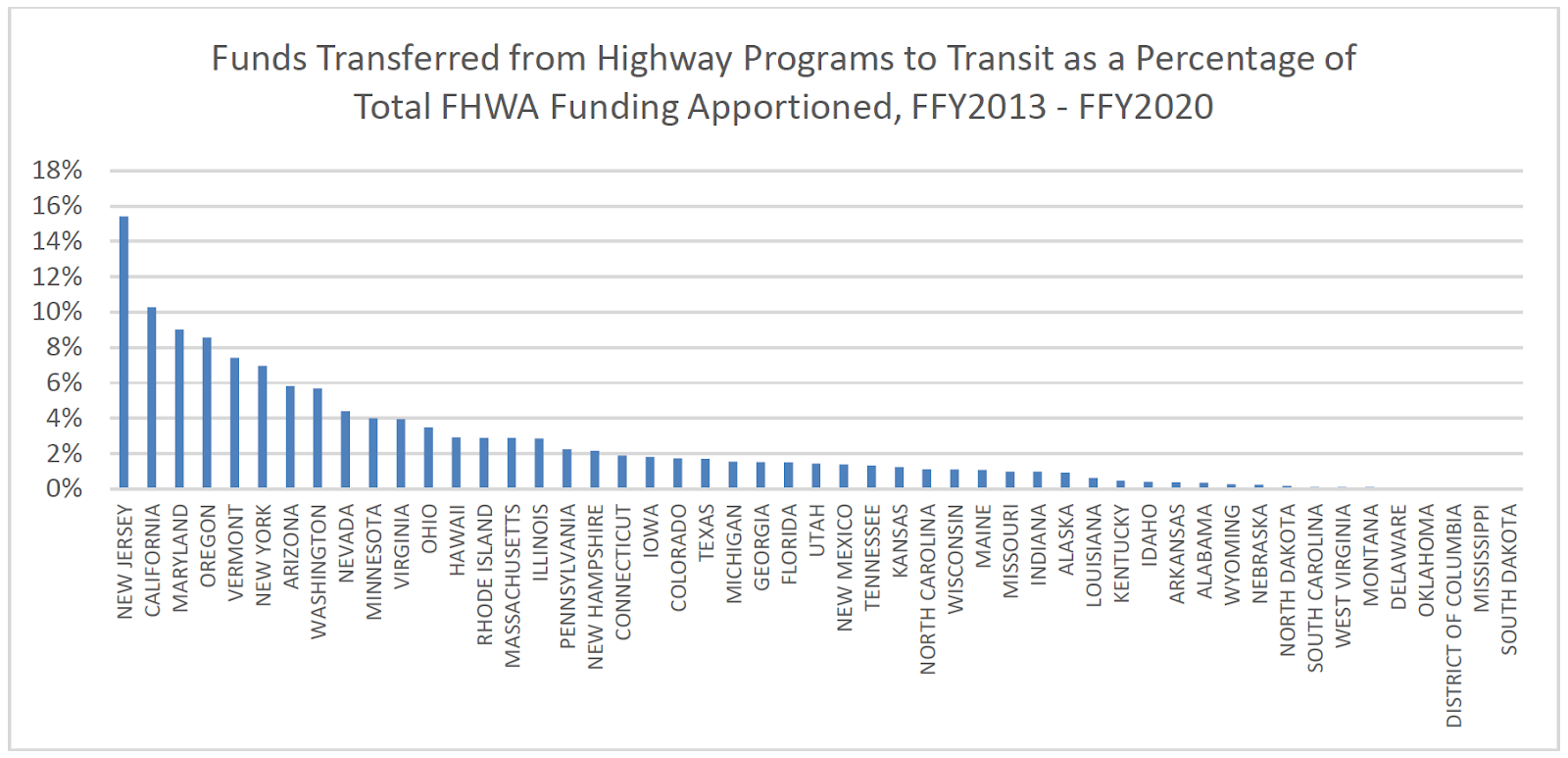

Federal transportation funding is highly flexible, as we’ve pointed out; most of the federal highway funds that states and Metropolitan Planning Organizations receive can pay for public transit projects. Unfortunately, most states rarely exercise this power, forgoing an important tool for funding transit. A recent report from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program shines a light on this issue, revealing that by one measure, states “flexed” less than 4%1 of their federal highway funds for transit projects between 2013 and 2020.

Only eight states were “superflexers,” transferring more than 4% of their federal highway funding to FTA: Nevada, Washington, Arizona, New York, Vermont, Oregon, Maryland, California, and New Jersey.

The two highway funding programs most commonly flexed to transit are Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) and the Surface Transportation Block Grant (STBG), which MPOs have significant authority over. But other programs can fund transit as well, including the National Highway Performance Program (the largest highway formula program) and the Carbon Reduction Program.

What makes a state decide to use highway funds for transit? The report offers a simple conclusion: It largely comes down to “state and regional priorities.” Where state and local decisionmakers value transit, states use more of their highway dollars for public transportation. Beyond that, it matters whether transit agencies have the capacity to plan, design, and deliver projects; are there enough transit projects in the “pipeline” to justify flexing funds?

State leadership

Vermont, a state with fewer than 650,000 residents, shows the potential for flexible funding to support transit as an essential service in a largely rural state. Since the early 1990s, Vermont has used flexible funds to beef up bus, demand-response, and commuter service.

As state officials explained to the Government Accountability Office in 2012, Vermont’s low density means it receives few federal transit formula funds. Flexible funds allow the state to better meet residents’ needs. In many years, the state “flexes” enough highway dollars to effectively double its federal transit funding, and has continued this approach since the pandemic. From 2022 to 2025, for example, Vermont plans to spend $205 million in federal funds on transit; $94 million of that (46%) will be flexed dollars. The state also plans to flex another $26 million in highway funds to Amtrak service in that period.

This allows Vermont transit systems to punch above their weight. In 2019, the state’s per-capita spending on transit was $93, more than in urban states like Virginia, Michigan, Georgia, and Florida. During the busiest days, more transit vehicles were on the road in Vermont than in Mississippi, New Mexico, or West Virginia, all larger and more populous states.

New Jersey offers a more urbanized example. The state transferred more of its federal highway dollars (15%) to FTA than any other in the country, primarily using CMAQ, often to pay for routine needs like new buses and train cars. The state also makes heavy use of tolls to fund transit, using hundreds of millions of dollars from the NJ Turnpike Authority to subsidize rail and bus service run by New Jersey Transit, and using federal “toll credit” as a local match for federally funded projects.

These practices show that New Jersey values transit. But they could also be seen as mitigation for the fact that NJ Transit lacks dedicated funding streams, relying on annual budget appropriations that make long-range planning difficult. As the advocacy group Tri-State Transportation Campaign has pointed out, the agency has long diverted funding from its operations budget to capital projects, shortchanging service and reducing its ability to keep fares affordable. In other words, New Jersey uses the flexibility of highway funding in part to make up for a lack of consistent state support.

Metropolitan leadership

In recent years, California’s transportation department (Caltrans) has taken a multimodal approach to transportation. But the main reason California “flexes” a relatively high percentage of federal funds to transit is because state law empowers MPOs to make those decisions.

Since 1997, California’s MPOs have had authority over the majority of federal highway dollars, and several regions have chosen to prioritize transit. Take the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, in the San Francisco Bay Area. Out of $652 million in federal highway funds that the agency programmed between 2018 and 2022, more than $150 million went to transit projects including new train cars for BART, transit-priority lanes in Oakland, bus stop improvements in Marin County, and support for a task force working to help plan for ridership growth.

While California is unique in the extent to which MPOs control federal funding, municipal leadership can make a difference anywhere. The report cites the Capital District Transportation Committee – the MPO in the Albany, NY region – as an example. For several years, the regional government programmed CMAQ funding to expand bus service and develop bus rapid transit, such as the Capital District Transportation Authority’s “BusPlus” Red Line. But in 2016, the region lost eligibility for CMAQ after the Environmental Protection Agency decided local air quality no longer violated ozone standards.

The MPO began programming other road funding for BRT to make up for it. Not only that, it used the power of persuasion to convince the New York State DOT to spend National Highway Performance Program funds for transit. As the report put it, Capital District leadership and staff “have consistently made the case that local funding needs are important to the operation of the entire regional transportation network,” and because transit runs on roads that are part of the National Highway System, that there was “a strong case for using federal highway funding to” support it. In 2020, CDTA opened the second rapid-bus route in the region, the Blue Line.

During the first 2 years of the Biden administration, Congress appropriated unprecedented levels of funding to transit, as well as significant funds through the “bipartisan infrastructure law.” The outlook for future federal support looks less clear. The necessary work of expanding and maintaining transit systems requires pro-transit state and local leaders to take full advantage of federal flexibility, in addition to raising their own sources of funds.

- It’s important to note that this is not the only type of flexibility in federal law and could underestimate states’ use of flexible funds. States can also spend federal highway grant funds on public transit without transferring the funds to FTA for oversight; however, this is rare given the administrative benefits of doing so.