In late 2019, the City Council in Kansas City, Missouri, voted to increase its subsidy to the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority to make bus trips free on routes that begin and end within the city. A Denver council member has called on the Regional Transit District to follow suit. County commissioners in Miami and Houston have suggested that transit staff study the issue.

Last year, TransitCenter pointed out that low-income transit riders tend to cite improving service as a higher priority than reducing fares, and that policy makers should act accordingly. With more cities now exploring fareless transit, we’d like to take a deeper dive into the pros and cons.

In brief, the case for zero-fare transit is strongest at small agencies with low ridership, where going fareless can improve riders’ experience with minimal impact on current service capacity. For agencies with significant ridership or agencies looking to put good transit within reach of more people, however, forgoing all fare revenue would substantially impede the ability to provide service, let alone improve or expand it. At these agencies, more targeted approaches to fare policy are necessary.

Most cities in the U.S. need massive service expansion in order to extend access to good transit to millions of people who lack it today. Several agencies are struggling under current budget conditions just to provide scheduled service and retain transit operators. Public officials can tackle the problems that free transit addresses without depriving agencies of the resources to run buses and trains, through policies like low-income fare programs, decriminalizing fare evasion, and all-door bus boarding.

Service, safety, and affordability all matter

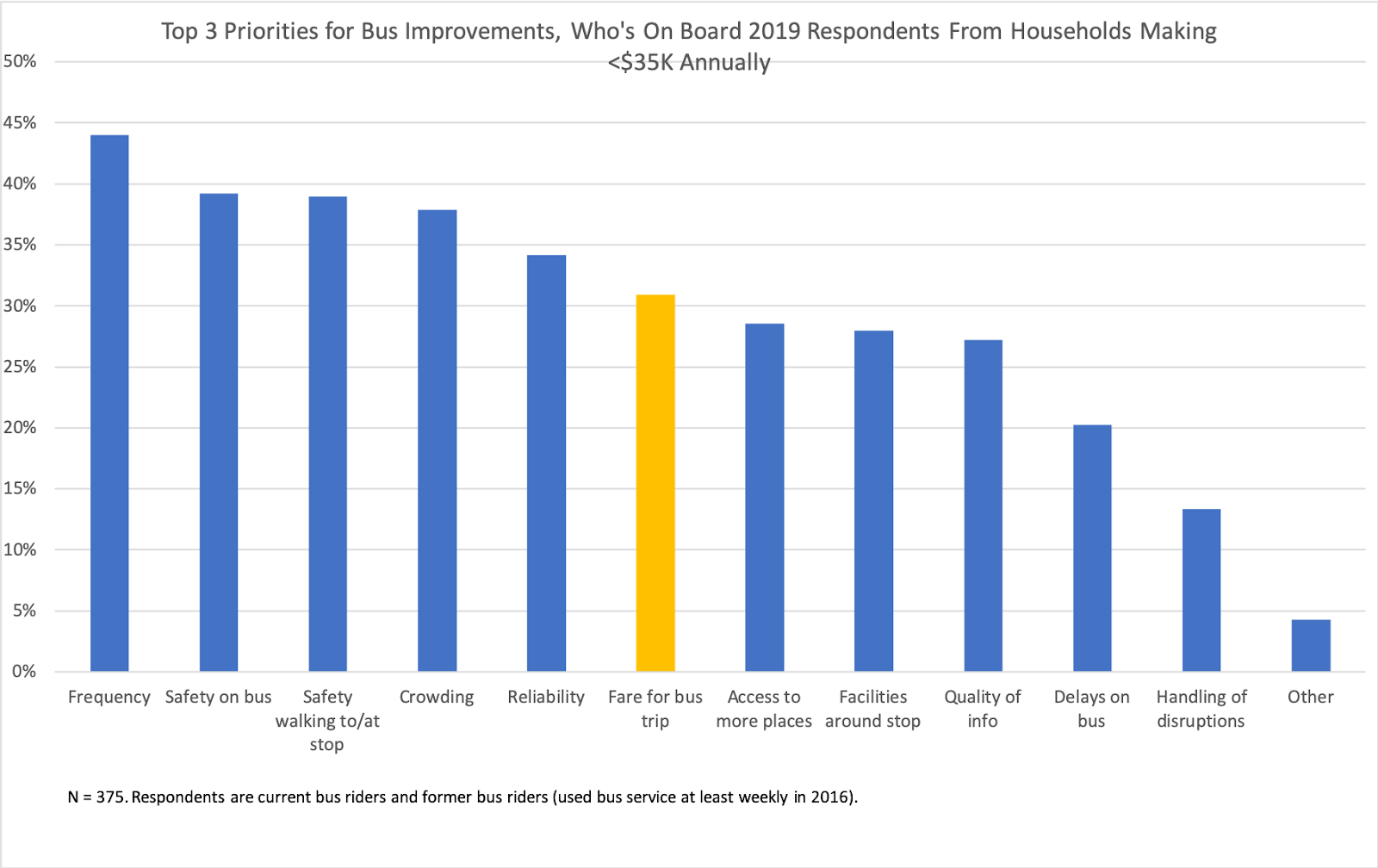

Transit riders at all income levels tend to say that service and safety are their most pressing priorities. In 2018, TransitCenter surveyed current and former transit riders in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Seattle, Denver, Pittsburgh, and New Orleans. Bus riders with household incomes below $35,000 a year were most likely to cite service and safety as the areas most needing improvement.

(There was no significant change when looking at respondents from households making below $25,000 a year, or below $15,000.)

These rankings are not surprising given the punishing consequences of infrequent, slow, and unreliable transit. In New York City, home healthcare workers lose hours of their lives every day to lengthy and variable commutes, have to pay for car service or Uber when transit runs behind schedule, and get docked pay for being late. Addressing the failings of transit service yields enormous material benefit to people.

The price of the fare matters, of course. When Boston-area transit riders who received food stamps were given half-priced farecards, they increased their transit use by 30% and took more trips to healthcare and social services. But when asked what the biggest problem was with transit in Greater Boston, they most often cited unreliability.

The size of the transit agency matters too

Some proponents of free transit argue that the costs of fare collection can exceed the revenues — but this is true only at the tiniest agencies. For example, a 2018 analysis recommended against introducing fares at the currently free Cache Valley Transit District in Logan, Utah, which operates 22 vehicles and serves 5,700 passenger trips on an average weekday.

At Intercity Transit in Olympia, Washington, which serves 15,000 trips on an average weekday, agency staff decided it was worth going fare-free — but not because fare collection was a drag on revenue. The transit agency brings in $2.2 million in farebox revenue annually, and spends $649,000 a year on collecting fares. Fare collection more than pays for itself, even including the looming need to upgrade the fare payment system.

Rather, agency staff said that removing fares provides benefits like a more seamless customer experience and reduced dwell time at bus stops, while avoiding discriminatory fare enforcement. The agency could proceed because the $1.5 million in foregone fare revenue accounts for just 2.5% of its budget.

But at larger transit agencies, the foregone revenue would be much greater, and so would the hit to their capacity to provide service. At Houston METRO, which carries about 280,000 trips on an average weekday, fare revenues are approximately $68 million a year. An upgraded fare system is estimated to cost $100 million spread over the next 15 years (about $6.5 million per year), while routine administrative and repair costs associated with fare collection amount to $3 million annually. Fare inspection also consumes some of METRO’s $32 million police budget, but fare inspectors account for a fraction of the total police headcount.

The largest American transit agency, New York’s MTA, receives more than $6 billion annually from fares — six times the amount of revenue projected to come from congestion pricing, which required a multi-decade political effort to enact.

Accomplishing the goals of fareless transit in other ways

New York, Seattle, San Francisco, and other cities have made progress on transit affordability with discounts and free fare programs for people with low incomes, kids and students, senior citizens, and other groups. These programs are not frictionless — they require participants to sign up. But the process can be as simple as enrolling in SNAP and other widely-used assistance programs.

Beyond affordability, the other benefits of fareless transit can be accomplished without detracting from agencies’ capacity to provide service. All-door boarding with proof-of-payment fare collection, for instance, can make bus service faster and more reliable.

Fare evasion should be decriminalized, with unbiased enforcement procedures and reasonable penalties, including the option to avoid a penalty by enrolling in a low-income fare program. Note that the problem of racially discriminatory policing in transit is larger than fare-related stops — neither decriminalizing fare evasion nor making transit free is a substitute for deescalation training, anti-bias measures, and other policing reforms.

The big idea U.S. transit needs: Run far more service, in far more places

A frequent question is “why not both”: Why not go fareless while also working to improve service? The reason is that the household costs imposed by the absence of good transit service stand out as the much more pressing problem to address. Transit in most U.S. cities is so infrequent and unreliable that major service improvements must be priority number one.

In most U.S. cities, transit is not a viable travel option for most residents with low incomes. In Los Angeles County, just 27% of residents live near transit that operates at least every 15 minutes during the day. In Miami-Dade County, just 18% of residents do. In Kansas City, fewer than 1 in 10 residents do.

As a result, a small percentage of poor residents ride transit in these places. In Los Angeles County, only 14 percent of workers below the poverty line commute using transit (according to the American Community Survey 2017 5-year estimates); in Miami-Dade County, Florida, 12 percent; in Kansas City, 9 percent.

Across the country, transportation and land use patterns have forced low-income households into financially unsustainable car dependence. U.S. automobile debt is at the highest level ever recorded, and poor families often struggle to maintain access to a vehicle, going in and out of car ownership as expenses pile up. Transit that is sparse and cheaper than driving has not solved this problem — making sparse transit free won’t solve it either.

The simple but radical idea that would make transit relevant to more people is to run a lot more transit service. Experience in Canada, which has similar land use but far more transit service, suggests that U.S. regions should aim to double, triple, or quadruple the amount of service they provide. In the Toronto suburbs, for example, buses run every 5 minutes (and get high ridership) in a land use context that might see hourly service in the U.S.

A few U.S. cities have recently taken steps toward major service expansion. In 2016, Indianapolis voters approved a tax increase that will eventually increase bus service by 70 percent. Nearly three-quarters of Seattleites now live within walking distance of frequent transit, compared to one-quarter in 2015.

Far more common is the situation in Denver, where low transit operator pay is making it hard just to run the current scheduled service. Even in cities like Seattle that have recently added service, there remains enormous unmet need to run more transit. The priority for new operating funds should be expanded service.

To improve transit access in U.S. cities, advocates should focus on expanding service while removing affordability barriers in a targeted way: Eliminate transfer fees, introduce fare capping, and provide discounts or free trips to riders with low incomes, kids under 18, and older residents. This is not because universal free transit is too ambitious; it’s because free transit won’t do enough to confront the transportation inequities that exist in U.S. cities today.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

Transit advocates, organizers, and riders are calling on local and state agencies along with the USDOT to advance projects designed to improve the mobility of Black and Brown individuals at a time when there is unprecedented funding and an equitable framework to transform transportation infrastructure, support the climate, and right historic injustices.

Read More