Summary:

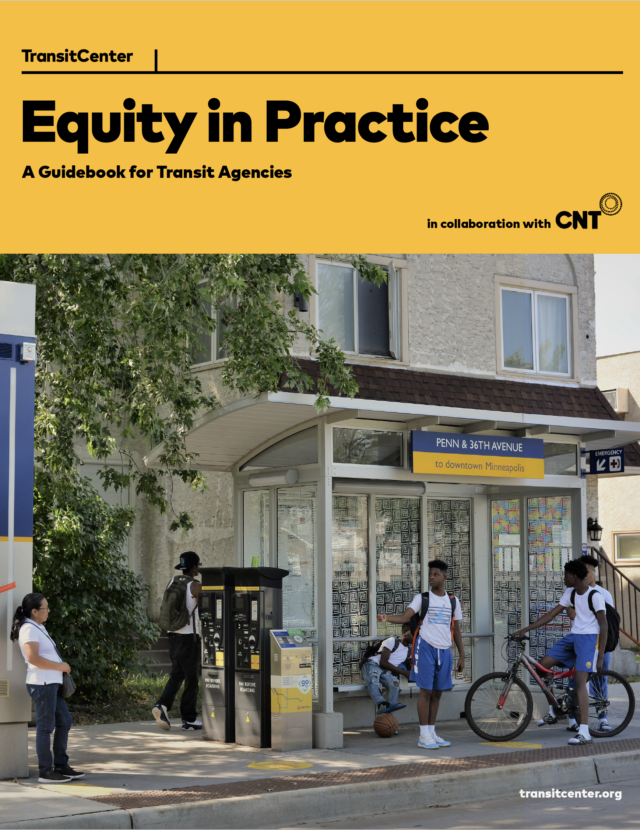

Every day public transit agencies make decisions that affect the health, economic status, and social well-being of transit riders and local communities. Decisions like where to site a bus stop, how to change a service schedule, how much to charge for a trip, or which stations should receive capital improvements affect people’s access to jobs, education, medical care, and other necessities. And in places where transit provides abundant access to these destinations, household transportation costs are more affordable, economic mobility is higher, and harmful automotive emissions are lower.

Too often, these important decisions are entrusted to transit agency leadership and staff who do not reflect the diversity of riders and communities most affected. In the public transit workforce, 66% of managerial and leadership positions are held by white people, despite accounting for only 40% of transit riders, while people of color are underrepresented in every area of the industry despite making up a majority of transit riders1. Black, Latinx, and Asian-American workers account for almost half of the total transit workforce—45%—but only 33.8% of managerial and leadership positions. Specifically, Black transit workers make up a quarter of the entire transit workforce and 27% of frontline workers, but less than 20% of managerial positions. Frontline workers, who are demographically more reflective of riders, have particular expertise about day-to-day operations and regularly interact with the public, yet are typically not included in decision-making.

While race and ethnicity are not the only determinants of someone’s personal experiences and levels of access and opportunity, there is a fundamental mismatch between who is making key transit decisions at public transit agencies, and who is most affected by those decisions.

What’s more, many transit agencies struggle to engage riders in public outreach. In addition to a history of mistrust between marginalized communities and government agencies, public outreach processes often don’t consider barriers such as work schedules outside 9-to-5 hours, or child- and home-care responsibilities.

The lack of inclusivity during the public outreach process and the lack of diversity among transit agency decision-makers has contributed to exclusionary systems and disparate outcomes that disproportionately burden lower-income groups and communities of color. To create better transit systems and achieve equitable outcomes, public transit agencies need more representative leadership, more inclusive internal decision-making processes, and more meaningful public engagement practices, where the people most affected can influence policy.

Read the full report.