Introduction

Access to high-quality public transportation can make cities more inclusive by increasing mobility and opportunity, particularly for people with low incomes and people of color. The role of a community is essential to fair and just transportation planning and decision-making processes. This can lead to prioritizing transportation investments that better enable people to meet their day-to-day needs—getting to work, school, the grocery store, the doctor’s office, and social and leisure activities. Allowing people to meet these needs creates long-term economic opportunities and helps people escape poverty. In addition to transit’s well-documented environmental and economic benefits, public transportation can be a powerful tool to advance racial equity and social justice in American cities.

Yet typical transit agency equity policy consists of little more than the box-checking exercise required by federal “Title VI” regulation, which is designed to limit further harm to people of color—not to advance equity. Compliance with a hard-to-enforce federal statute1 is not enough in cities striving to combat systemic inequities perpetuated by decades of racist policies that have excluded people of color from access to opportunity and wealth in cities. Transportation leaders have too often turned a blind eye to the historical and ongoing social justice implications of the institutions that build and operate transportation systems in the U.S.

Transit systems that are designed to work for a city or region’s most vulnerable populations will work for everyone. By establishing more inclusive planning practices transit agencies can build trust with the communities they serve. In turn, transit riders who feel respected by their transit system will be more inclined to keep using it. In other words, equity is not merely the right thing to do—it is also good for business, and a strategic imperative.

In other words, equity is not merely the right thing to do—it is also good for business, and a strategic imperative.

The legacies of urban renewal’s racist policies vary from city to city, but can be recognized throughout the US. In cities like Syracuse, Little Rock Baltimore and Minneapolis, redlining and major highway construction erased African-American and immigrant neighborhoods. Planners and policy-makers must engage at the local level with this history in order to make our cities inclusive places to live.

Formerly red-lined urban neighborhoods often face the highest affordability and displacement risks when major real estate and transportation investments are made, adding insult to decades of injury and generating inevitable pushback from long-time residents worried about cost of living and rent increases in their communities.

Unfortunately, many of the same funding and planning policies that gave rise to today’s inequitable system persist. This is especially apparent in the neglect of urban bus systems, which carry racial and cultural stigmas formed during the height of white flight in the 1960s and 70s. In the words of one commentator in a recent University of Texas report, “Dallas’ income inequality and lack of upward mobility are directly related to the failures of its public transit agency.” The Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) system, which boast’s the nation’s “longest light rail network,” appears to have lost sight of its mission to provide “efficient and effective” transportation that “improves the quality of life” for Dallas area residents.

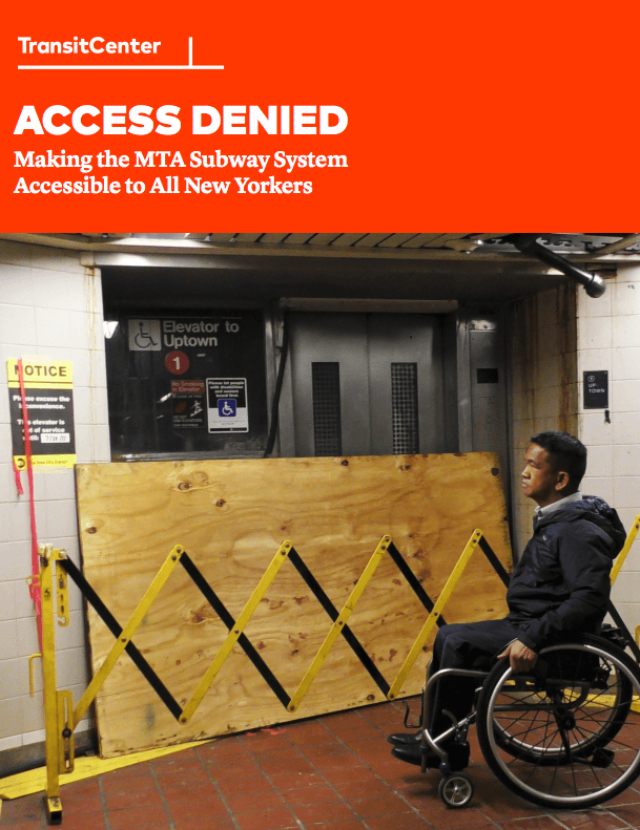

Misplaced, inequitable planning and funding priorities are also apparent in the nation’s largest transit market. At a cost of $10 billion, New York City’s East Side Access project is forecasted to support 162,000 daily trips from the city’s Long Island suburbs once complete. Meanwhile the city’s bus riders—already taking two million trips daily—compete for budgetary table scraps. Long Island Railroad riders’ median income is a staggering five times higher than New York City’s median bus rider—$144,251 and $28,455, respectively. Regardless of Title VI, state and federal tax dollars are often allocated to projects that, on balance, widen gaps in transportation access for low-income/low-wealth people and people of color.

Much transit equity research to date has focused on federal policy, with limited planning-oriented guidance for local and regional public transportation practitioners. Transit equity research has also neglected the need for state, metropolitan, and local transportation funding in addition to governance reform. These jurisdictions wield the most influence over transportation projects that could benefit people of color and people with low incomes.

Press

Recommendations

- Investment in transit service and capacity should directly address inequities in access to transportation

- Transit access practices such as fare policies should target high-need communities

- Dialogue between transit leadership and communities can build clearer understanding of needs and reduce resistance to transit projects or changes

- Transit planning should account for housing affordability, and improve access to and from affordable housing

- Transit operations and capital projects should support employment in low-income communities and communities of color

- Transit agencies should decriminalize fare evasion