Transit and Public Health: Separating Fact From Fiction

When the pandemic first intensified in the U.S., with New York as the epicenter, some observers rushed to conclude that transit was a unique causal factor. Subsequent research into the prevalence of the virus and how it spreads disproved this hypothesis.

Analysis by Tri-State Transportation Campaign, for instance, found that within the New York region, “density and transit are poorly correlated to COVID outbreaks.” Early fears of rampant spread via surfaces like poles and turnstiles proved exaggerated, as infectious disease experts identified respiration as the primary vector of transmission. Epidemiological investigations in other countries traced major spreading events overwhelmingly to venues like gyms, clubs, and restaurants, not transit.

COVID-19 can certainly be transmitted on transit, but the risk is lower than other enclosed spaces, according to epidemiologists. Three main factors explain the difference:

— People spend much less time on transit than in the workplace or at home.

— People talk less on transit than at venues like restaurants or bars, releasing fewer respiratory particles that may carry the virus.

— Transit vehicles are better ventilated than indoor spaces like offices.

The risk of transmission on transit also varies according to several factors, the main one being the current local prevalence of COVID-19. When case rates are high, the risk on transit will be higher, and when they are low, the risk will be lower. “If only one person in 10,000 has the virus, then you can do anything you want to for transportation,” said Tufts University Professor of Public Health and Community Medicine Dr. Jeffrey Griffiths.

In cities including Seoul, Taipei, and Hong Kong, where the 2003 SARS outbreak primed governments to respond quickly and effectively to the pandemic, millions of people—almost all wearing face masks— ride transit every day while viral transmission remains negligible. For U.S. transit agencies, the uncoordinated federal response and failure to decisively suppress the virus makes it more challenging to win back riders, but the international experience shows that it is possible to safely transport substantial ridership before the development of a vaccine.

The Challenge of Welcoming Riders Back

TransitCenter’s survey of major American cities suggests residents will resume riding transit in large numbers if transit officials and city governments address safety concerns and adapt service to align with shifting travel preferences. We commissioned YouGov to poll a representative sample of 2,198 adults in seven U.S. cities with major transit systems about their attitudes toward daily travel before a vaccine or cure for COVID-19 is developed. The survey was conducted via internet from July 17-27 in Los Angeles, New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Boston, and Washington, DC.

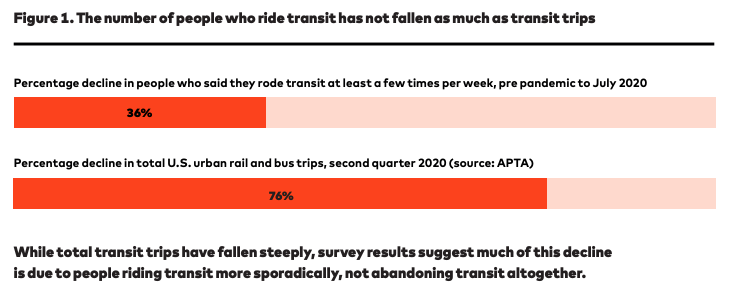

Among all respondents, 47% said they rode transit at least a few times per week before the pandemic, falling to 30% in July 2020. This decline tracks with a decrease in commute travel — nearly a third of respondents said they have stopped making trips to work or school. The decline in survey respondents who regularly use transit is substantial, but smaller than the roughly 75% drop in total transit trips that agencies typically observed. This implies that while some people have stopped riding transit, a significant share of the drop in trips is due to people riding less often. In other words, many people who formerly rode transit multiple times per day may now be riding sporadically, not abandoning transit altogether.

Actions for the Emergency and the Recovery

Protecting the transit workforce and transit riders

- Expand sick leave and quarantine policies. By expanding access to sick leave, reducing red tape, and compensating workers for time they must spend quarantined after contact with someone who has tested positive, agencies protect the health and wellbeing of their workforce and riders.

- Supply protective equipment, especially masks. Many transit workers share spaces with riders or other transit workers for extended periods of time. Agencies should provide all employees who work in these conditions with regularly replenished high-grade respiratory masks, like N-95 masks. For riders, agencies can make mask-wearing the easy choice by distributing masks to riders who do not bring their own.

- Ventilate vehicles and shared areas. All common spaces — including vehicles, depots, offices, and break rooms — should be ventilated to ensure circulation of fresh air to the maximum extent practicable. On buses, air intake by the front of the vehicle and venting toward the rear prevent recirculation of virus particles. Outfitting air conditioning ducts on trains and buses with stronger filters and sterilization systems likewise reduces risk.

- Communicate clearly with riders. To operate safely while COVID-19 remains a risk, agencies depend on riders to adopt new behaviors, like mask-wearing, and adapt to new conditions, like the public health imperative to avoid intense crowding. Agencies must gear public communications to help riders adjust and make safe travel decisions.

Photo: LA Metro

Safe and equitable service provision

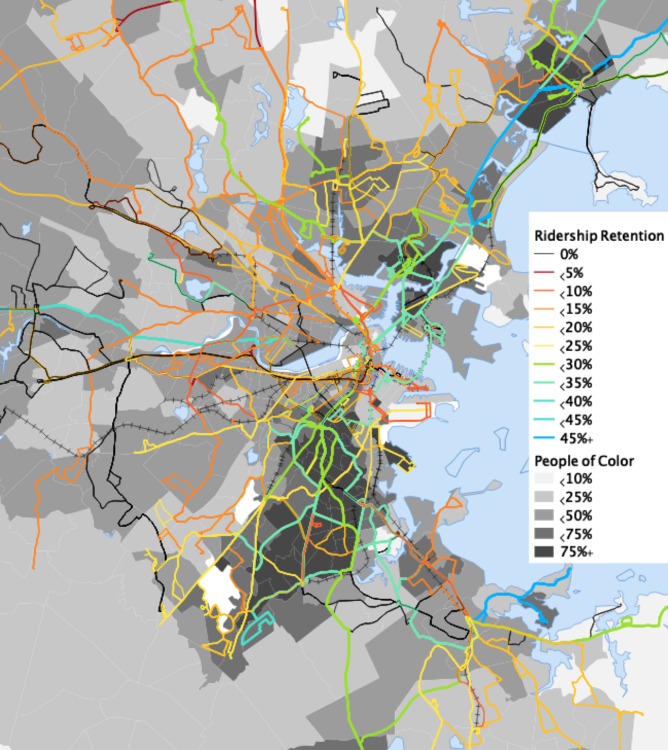

While overall ridership has fallen, trips to places like hospitals and distribution centers remain high. Compared to typical conditions, during the pandemic Black and brown Americans account for a higher share of transit ridership. Essential workers who rely on transit are also more likely to commute outside the 9-5 office schedule. As a result, changes in ridership volume are far from uniform across transit networks. Route- and stop-level data released by the MBTA, for instance, indicate that routes serving predominantly Black, brown, and low-income neighborhoods have generally retained a much greater share of ridership than routes serving predominantly white and affluent neighborhoods.

Reverting to pre-pandemic schedules — be it weekend or regular weekday service — is not responsive to these new ridership patterns. Agencies should adjust schedules by reallocating service from low-ridership to high-ridership routes, especially in light of the need to reduce transit crowding for Black and brown riders with health conditions that elevate the risk of severe illness or death from COVID-19.

In Boston, routes serving predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods have retained more ridership during the pandemic.

On-street transit priority

Car traffic is rising faster than transit ridership as cities reopen. At the same time, bus service has retained a greater share of ridership than other modes of transit, perhaps reflecting that essential workers are more likely to travel by bus. Without countermeasures in place, traffic congestion threatens to overwhelm bus service, making trips even slower and less reliable than before the onset of COVID-19.

City DOTs should implement quick-build bus lanes to maintain speed and reliability, insulating transit from a rise in car traffic volumes. Projects can be completed in weeks or even days, not months.

Boarding procedure and fare policy

During periods of elevated risk, agencies have suspended fare collection on buses, shifting boarding to the rear door. This eliminates potential contact during fare transactions and generates space — often demarcated with a partition — between the bus operator and the passenger area. Agencies should only resume bus fare collection when case rates are low enough that the virus can be contained and suppressed with test-and-trace methods. Given the economic stress many transit riders are enduring throughout the COVID-19 emergency, agencies should consider extending fare-free policies or offering additional discounts for riders with low incomes.

Demand management

With COVID-19 projected to tilt travel decisions toward driving private cars, pricing and other financial incentives are a powerful countervailing tool municipalities can use to reduce automobile traffic and help keep bus riders moving. Parking meter prices that rise where and when demand is highest can reduce double-parking and cruising for empty spaces — driving habits that slow down buses in commercial districts.

Municipal governments also have some ability to shape travel demand by influencing working hours, whether with a bully pulpit or with regulation, as well as their own internal practices as large employers. Staggering shifts, such as having some employees work 7:00 AM to 3:00 PM and others from 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM, can reduce the peak crowding on transit that occurs when many people are trying to arrive at the same time.