TriMet light rail operator, via Flickr

Without frontline transit workers, cities would not be able to function during the COVID-19 emergency. Despite increased risk of contracting the virus and a lack of personal protective equipment, transit workers continue to report for duty. Their heroic efforts ensure that medical workers, grocery store employees, and other essential workers can continue to provide the goods and services people depend on to survive while the rest of the population stays home.

Across the United States, in every industry deemed essential, frontline workers have been asked to bear the burden of keeping businesses open. This has led to a disproportionate impact on people of color and working class Americans.

The same is true within the transit workforce. Frontline transit workers who must leave their homes for each shift – especially vehicle operators – are more likely than non-frontline workers to be people of color or to come from low-income households. Such disparities exacerbate existing inequities at transit agencies and place an uneven weight on the shoulders of vulnerable workers and their families.

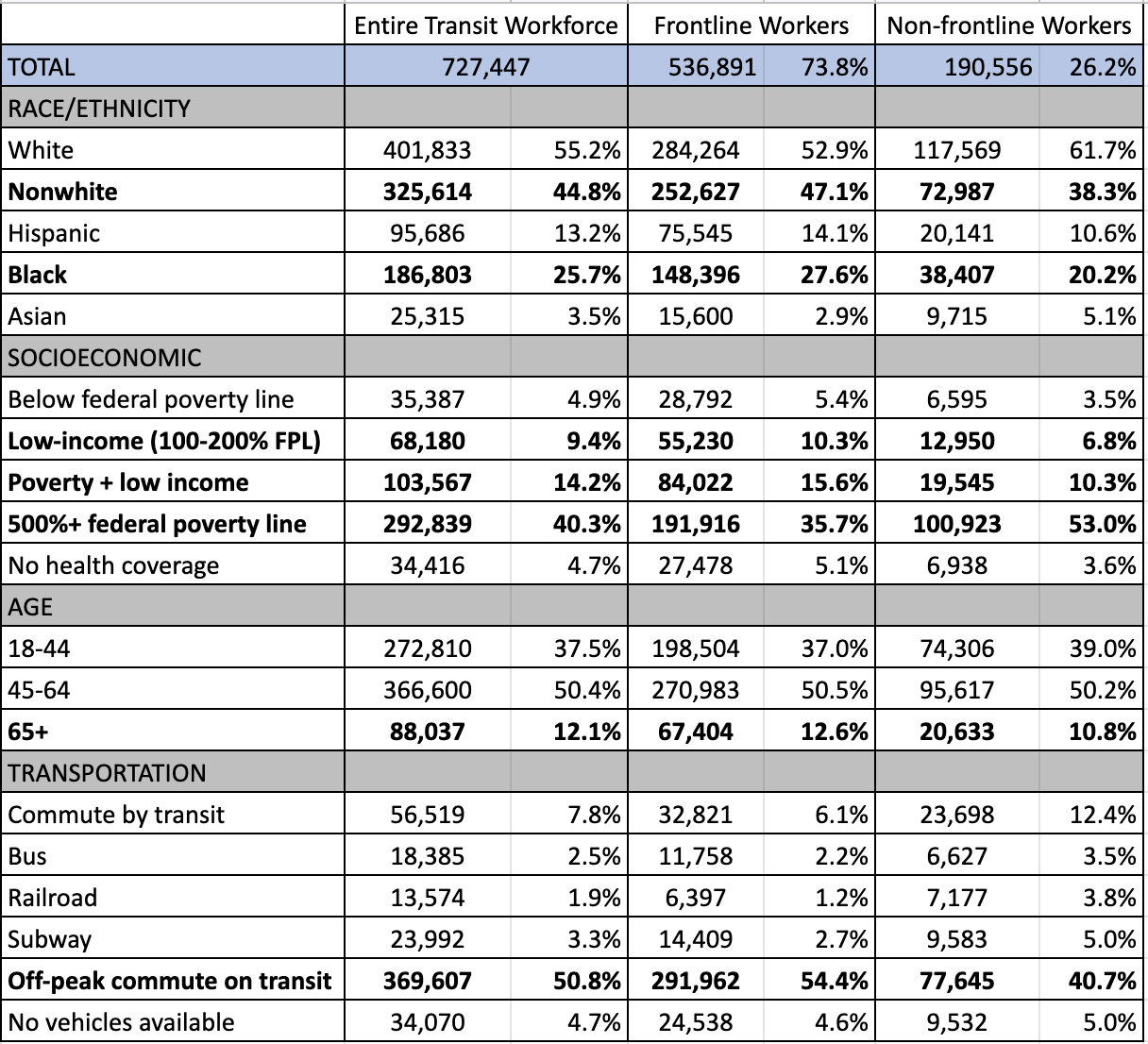

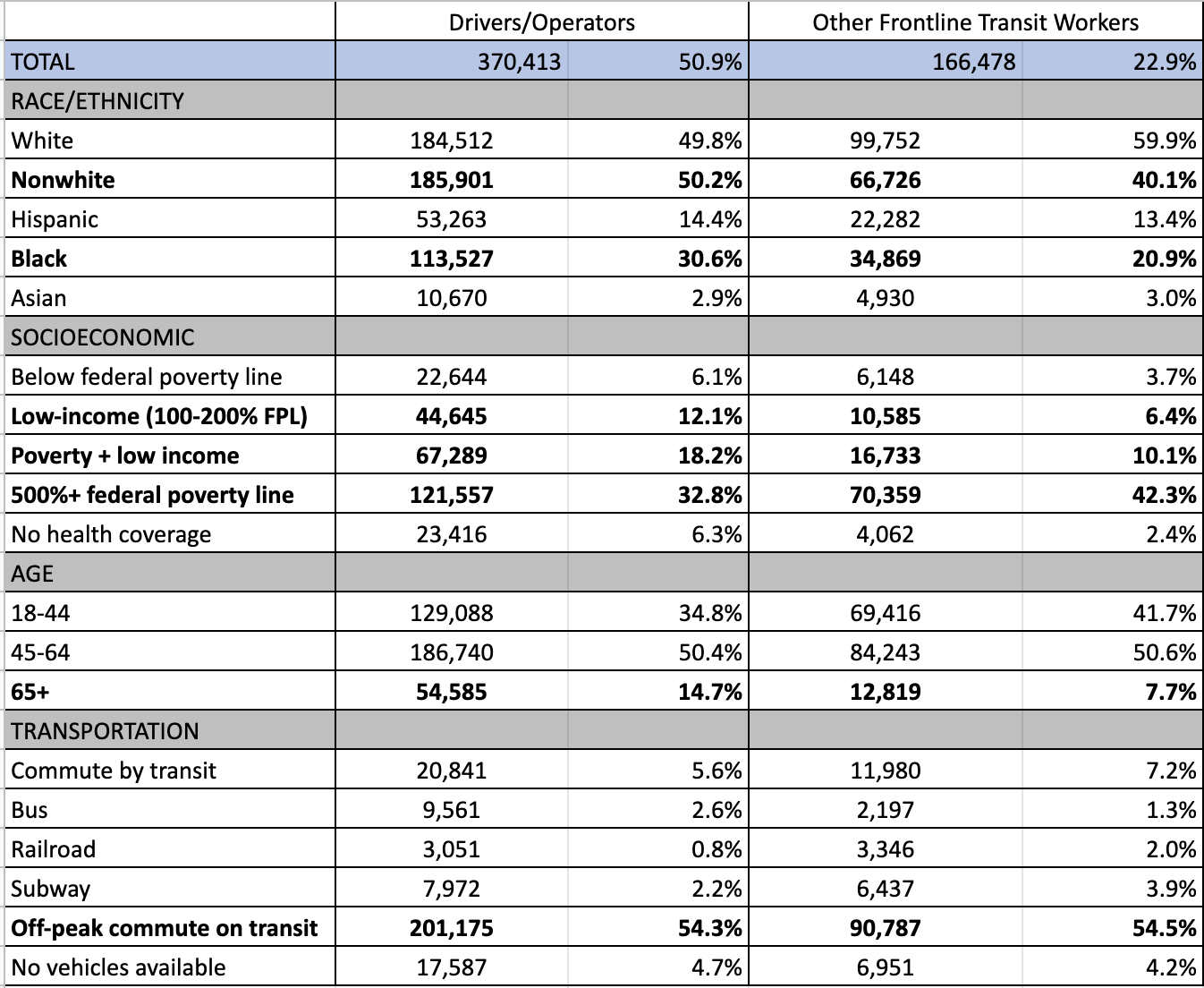

Using American Community Survey data, TransitCenter analyzed race and income within the transit workforce, comparing frontline workers like bus operators, cleaners, mechanics, and others who can’t work from home, with non-frontline workers like managers, service planners, and others who can work from home.

The findings include:

- Among frontline workers, a greater share are black (28%) or Hispanic (14%) compared to non-frontline workers (20% and 11%, respectively).

- A greater share of frontline workers are from low-income households (10.3%) compared to non-frontline workers (6.8%); fewer frontline workers are in households earning 500% or more of the federal poverty line (35.7%) compared to non-frontline workers (53.0%).

- Frontline workers are more likely not to have health insurance (5.1%) than other transit workers (3.6%).

- Frontline workers are more likely to be 65 years or older (12.6%) compared to non-frontline transit workers (10.8%).

Here’s the breakdown of frontline and non-frontline transit workers by race, income, age, and other factors:

Here’s the breakdown between vehicle operators and other frontline transit workers:

These disparities between frontline workers and the office and management staff make a focus on worker safety especially important. An agency’s lack of safety preparedness is more likely to hurt workers from black and brown communities as well as those without access to health insurance and those over the age of 65.

At the outset of the pandemic, the concerns of frontline workers did not always take priority. Slow responses from management created extra difficulties for frontline staff. “Things are moving very slowly in terms of management decisions, and due to the urgency of the virus, that sluggishness is felt now as never before. That sluggishness has resulted in operators getting infected, and will continue to result in more of the same,” a bus operator at a West Coast agency requesting anonymity told TransitCenter.

In hard-hit New York, MTA management initially rejected frontline staff requests to wear masks. “They’re putting public perception over employee health once again,” train operator Ben Valdes told Gothamist in early March. “I know a lot of people are saying, ‘Oh the mask doesn’t work,’ but we have no faith whatsoever that the MTA has a plan to protect us.”

In the following days, hundreds of MTA employees contracted coronavirus and eight died as the MTA rushed to find personal protective equipment for staff. As of April 8, the number of deaths had risen to 41 with over 6,000 workers falling sick or self-quarantined. Such decisions undermine employee trust in management and an agency’s ability to provide sufficient service through a crisis.

To lessen the burden of operators and frontline employees, agency management must make efforts to ensure that the concerns of frontline workers are heard and then move quickly to remedy shortcomings and make sure safety needs are met. Agencies may need external assistance themselves – they lack access to sufficient supplies of masks and other protective equipment just as other businesses do – but they must strive to address the fears of their workers.

When the crisis ends and transit agencies begin to assess their responses, efforts must be made to ensure that agency management reflects the demographics of frontline workers and riders. Agencies reflective of the communities they serve should be better positioned to hear the concerns of vulnerable riders and frontline staff and work with them to create a more robust response.