Whether it’s streetcars or autonomous shuttles, the recent history of transportation planning is littered with projects designed more to attract development than to meet people’s mobility needs. But the transit-as-bauble era may have run its course in Pittsburgh. After a multi-year battle, the advocacy group Pittsburghers for Public Transit (PPT) fended off the Mon-Oakland Connector, an autonomous micro-transit project championed by Mayor Bill Peduto.

In December, the Pittsburgh City Council reallocated money from the project to support affordable housing and street improvements instead. PPT’s victory provides a template for how advocacy groups can push back against poorly conceived transportation projects, and secure tangible improvements in the process.

From the beginning, it was apparent that the project wasn’t grounded in community needs. In 2015, the City of Pittsburgh applied for a “Smart City” grant from the US Department of Transportation, requesting federal funding for a network of electric autonomous shuttles. “The city didn’t win the grant,” says Laura Wiens, executive director of PPT, “but the project didn’t functionally change very much after that.”

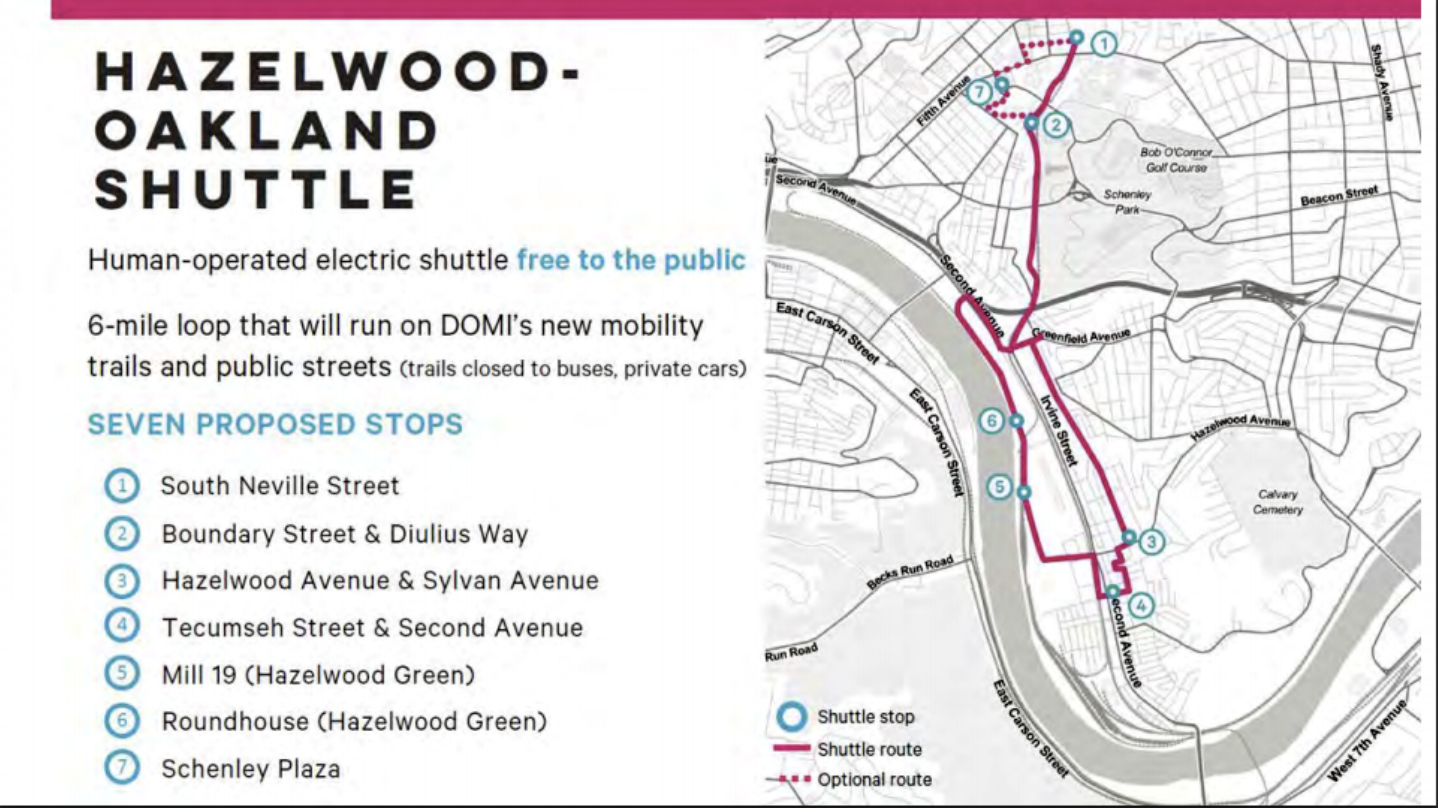

In both the “Smart City” application and subsequent iterations of the project, the Mon-Oakland Connector was described as a “mobility corridor” that would connect the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon with the neighborhoods of Hazelwood, Oakland, Greenfield, and Hazelwood Green, a development site along the Monongahela River. Running in large part through the city’s historic Schenley Park, the “Connector” was designed as a series of multi-use paths to accommodate pedestrians, cyclists, and someday, autonomous electric shuttles. Pittsburgh taxpayers would have been on the hook for $23 million of the infrastructure costs associated with the project, while the universities and the three Pittsburgh foundations that own Hazelwood Green planned to cover the cost of purchasing and operating the shuttles.

Proposed map of the shuttle system

Residents of neighborhoods affected by the project were not involved in the Smart City application. By the time they learned of the city’s intentions for the corridor – in a 2015 Post Gazette article – the concept was nearly fully cooked.

Autonomous shuttles were the last thing on residents’ minds, says Wiens. Hazelwood and Greenfield, in particular, face longstanding transportation challenges, and residents had been asking the city for basic amenities for years – like better sidewalks, lighting, and flood protection. But many of those requests had fallen on deaf ears. Meanwhile, proponents of the Mon-Oakland Connector were eager to present the project as something that directly addressed the needs of the neighborhood’s most vulnerable residents. “The City claims that the Connector will enhance the mobility options and transportation for the working class and underserved community within that corridor, “ says Wiens. “But they will see very little benefit from a micro-transit shuttle project pilot.”

As a transit project, the AV shuttles fail spectacularly – the most optimistic projections estimate that they would serve a maximum of 180 daily riders. “It’s such a lackluster project,” says Wiens. “Serving 180 people at a cost of millions and millions of dollars to the city.” In its public communications about the project, PPT has consistently emphasized that residents would be better served by focusing on improving existing transit service.

In addition to the project’s inability to move people at scale, there were also abiding suspicions about who the project was designed to benefit. Hazelwood Green is a 187-acre former brownfield site that the city hopes will someday host Pittsburgh’s version of Silicon Valley. “What has become increasingly clear is that the Connector was a development project masquerading as a transit project,” says Wiens.

Wiens says the project is par for the course when it comes to Mayor Peduto’s techno-optimist approach to city governance. “The Mon-Oakland Connector is just the most egregious example of the city’s prioritization of transportation projects that are designed to increase profits for private developments, or to provide public resources to support venture-backed mobility services.”

Historically, the city of Pittsburgh hasn’t provided direct funding to the city’s transit system, the Port Authority, which carried more than 200,000 trips per day pre-COVID. But the city has spent time and energy on speculative technologies to address transportation challenges. In addition to the Mon-Oakland Connector, Wiens points to the city’s willingness to let Uber test drive autonomous vehicles on city streets, the Move412 “mobility as a service” platform, and the city’s 2070 Mobility Vision Plan’s focus on hyperloop, vertical take off airplanes, autonomous vehicles, and personal rapid transit, as evidence of where the city’s priorities lie.

For two years, PPT worked with residents and neighborhood groups to develop a different vision to the Connector. “We’ve constructed a community-generated alternative plan that really meaningfully addresses the transit and bike and pedestrian needs of the community,” says Wiens. “We call it the ‘Our Money, Our Solutions’ plan.”

The plan proposes adding weekend service to the 93 bus, which currently runs between Oakland and Hazelwood, and extending the 75 bus into Hazelwood. It also emphasizes basic amenities like better sidewalks and enhanced lighting as key to helping people to get around safely in the neighborhoods. Wiens says that none of the solutions in the “Our Money, Our Solutions” plan reinvented the wheel – PPT was merely aggregating ideas residents had suggested in various community plans and forums.

PPT also worked with students at Carnegie Mellon to produce “The People’s Audit of the Mon-Oakland Connector,” which evaluated the merits of the Mon-Oakland Connector against the transit expansion proposed by “Our Money, Our Solutions.” “By every metric, by speed and implementation, and capacity and ridership, and destination, the expanded transit did better than the shuttle,” says Wiens. She says that the ideas in “Our Money, Our Solutions” connect more people to more jobs, grocery stores, and healthcare providers than the Connector project, all at a lower cost to the public.

Wiens says there were never any real community champions of the Connector, but a powerful coalition of interests – city government, foundations, and universities – kept it chugging along despite the clear lack of public enthusiasm. Rather than accept the project as an inevitability, PPT kept the issue in the spotlight by organizing rallies and marches, and encouraging residents to show up at public meetings to speak out against it.

Public interest reached a fever pitch in October 2020, when, in a packed Zoom meeting, hundreds of constituents expressed their opposition to the Connector. “There was just a beautiful and overwhelming consensus that what the communities needed was actually more affordable housing and more access to enhanced transit service frequency,” said Wiens.

This outcry was enough to convince Council Member Corey O’Connor, who represents Greenfield and Hazelwood, that the plan was misguided. In December, O’Connor proposed an amendment to the Connector plan, which redirected $4.1 millon from the city’s FY21 commitment to the project toward affordable housing needs across the city. His amendment passed with unanimous support from the Pittsburgh Council.

Wiens says the $100 million municipal budget shortfall wrought by the pandemic likely helped to thwart the project. “What was problematic before the pandemic became unconscionable in this climate,” she said. “Funding this project would mean that other critical needs aren’t being met right now.”

But she emphasizes that continued vigilance is necessary. While the December vote means that the Connector cannot proceed as planned, the original $14.5 million earmarked for the project has yet to be reallocated. Her worry is that the Connector could limp along as a “zombie project,” waiting to be resurrected by an enthusiastic elected official. PPT is currently working with the city auditor to assess options for formally moving the money, and to make recommendations about how that money should be spent. “The Mon-Oakland Connector has shown us that there are resources available for our communities to have our needs met, provided that we are organized enough to take it,” says Wiens.

Peduto is up for re-election in the fall, and Wiens expects the issue to come up throughout the year as part of the mayoral race. “It’s not done until it’s done.”

She’s also not convinced that Pittsburgh has reached the end of the “smart city” trend. “There’s still such an infatuation with ‘smart city technology.’ The value proposition is there in the name, so it can be a hard thing to fight against.” She says a key to winning this argument is to identify what you want to see improved or funded, rather than just saying “no” to a project. “It is not inspiring to call for the defunding of a project without talking about what you want to invest in.”

Wiens views projects like the Mon-Oakland Connector as the ultimate manifestation of the upward redistribution of public wealth, because they aim to serve so few people. “I think that we should be very, very skeptical about claims that luxury kinds of transportation services are going to drive up a tax base, or bring new investment dollars and new jobs into a community. Let’s see the evidence of that, and then ask the public to weigh in on whether they think that subsidizing tech companies is the highest and best use of our public money.”

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

Transit advocates, organizers, and riders are calling on local and state agencies along with the USDOT to advance projects designed to improve the mobility of Black and Brown individuals at a time when there is unprecedented funding and an equitable framework to transform transportation infrastructure, support the climate, and right historic injustices.

Read More