At the end of February, the MTA launched a weekly fare-capping pilot – a milestone in the agency’s rollout of the OMNY fare system. With fare-capping, MTA is taking advantage of the new fare payment platform to make the rider experience more convenient and equitable.

Under the MTA weekly fare-capping pilot, people who pay for at least 12 trips with OMNY starting each Monday are not charged for additional rides through Sunday night. It is the equivalent of a 7-day unlimited MetroCard, with two advantages: Riders don’t have to cover the full cost of a bulk pass upfront, nor do they have to calculate whether paying for a bulk discount makes sense for them ahead of time.

With the current MetroCard fare structure, cash-strapped riders end up paying more for transit because they can’t afford the higher upfront cost of passes with unlimited trips. Fare-capping promises to correct that inequity. The discount kicks in automatically, and riders never have to pay more than the price of a single fare at a time.

In the pilot’s first month, more than 168,000 people earned free rides through OMNY, saving riders more than $1 million in fares. We applaud the MTA for this successful roll-out, and are encouraged by recent signs the program may become permanent. But to maximize its impact, the MTA should expand the pilot to include monthly fare capping.

If the MTA were to implement a 30-day fare-capping period, we estimate that 200,000 subway riders currently using the 7-day unlimited MetroCard would save on fares — around 4.4% of all regular subway riders as of October 2021. Riders would save more than $2.5 million in fares each month. Furthermore, most of these savings would accrue to riders in low-income neighborhoods. Monthly fare capping would be a great way for the agency to meet its own goal of instituting more equitable fare policies.

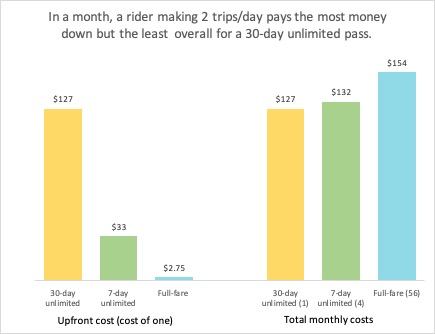

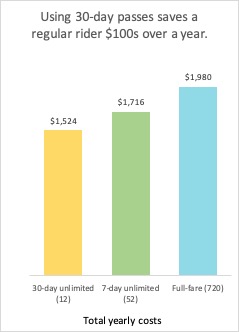

At $127, the 30-day unlimited MetroCard is currently the best value for daily riders and the fare product with the highest upfront cost. Over the course of a year, a twice-a-day rider who buys a dozen 30-day passes saves $192 compared to buying fifty-two 7-day passes and $456 compared to buying single rides. For families, these savings can add up to a significant portion of household income.

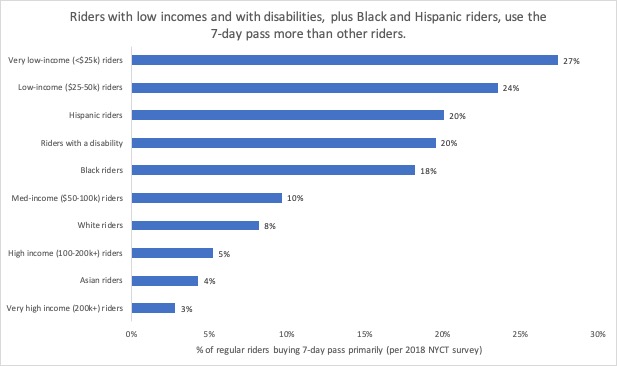

According to a 2018 NYCT rider survey, among riders who took at least 12 trips per week, 27% of people with household incomes below $25,000 used a 7-day pass — many times more than the share of riders with household incomes over $200,000 who used the 7-day pass (3%). This indicates that the upfront cost of a 7-day pass is much less of an obstacle to people with low incomes than the cost of a 30-day pass.

In October 2021, 7-day passes accounted for 24% of MetroCard swipes at subway stations in low-income tracts, compared to 15% at stations in affluent tracts. Black and Hispanic riders, and riders with disabilities, were also more likely to use the 7-day pass than other riders according to the 2018 NYCT survey. The current fare capping policy only helps single-ride users earn weekly cost savings, so people who already use the 7-day MetroCard don’t benefit.

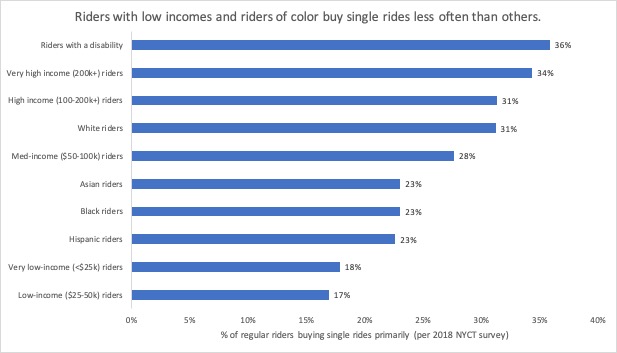

Further, riders of color and riders with low incomes buy single rides less than other straphangers, suggesting that they benefit from the current policy to a lesser degree than white and high-income riders do.

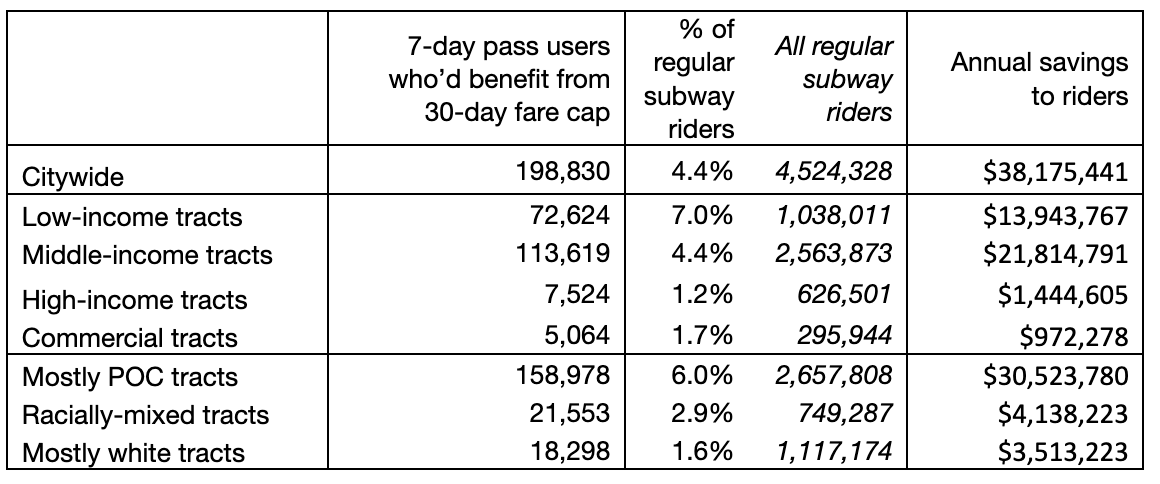

Using subway swipe data, TransitCenter projects that adding a 30-day fare-capping option would disproportionately benefit riders from neighborhoods of color and low-income neighborhoods:

- An estimated 7% of subway riders from low-income tracts use the 7-day pass but ride often enough to trigger the 30-day fare cap. In middle-income tracts and high-income tracts, the estimated share of riders who would benefit is 4.4% of riders and 1.2%, respectively.

- An estimated 6% of subway riders from tracts where most residents are people of color would benefit, compared to 3% of riders from racially-mixed tracts, and 1.5% of residents from mostly white neighborhoods.

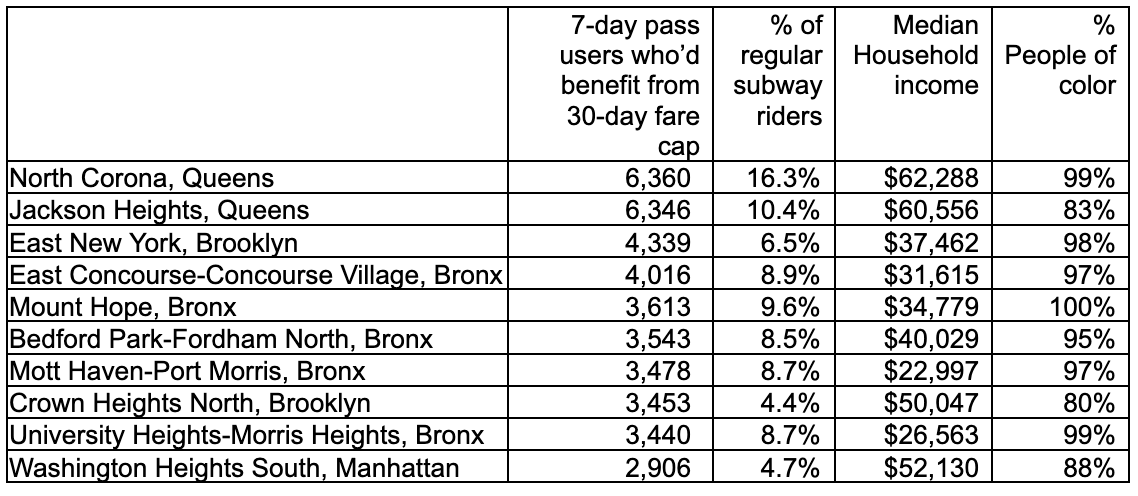

Neighborhoods with the most riders who stand to benefit from 30-day fare-capping:

These are conservative estimates that likely undercount the number of people who stand to benefit from a 30-day fare-capping option, because the data does not include people who primarily ride the bus. (Geographic fare swipe data is not available from MTA buses.)

Fare capping has benefits for the MTA that will only grow if it is expanded to monthly periods. Experts theorize that fare capping can boost ridership by eliminating the friction riders encounter when deciding how to pay fares. Additionally, the potential cost savings from fare capping incentivize riders to switch to OMNY, quickening the transition to the new payment method.

The launch of weekly fare-capping is an exciting new option for NYC transit riders. Combined with widespread distribution of OMNY cards to make the new fare payment system available to New Yorkers without smartphones or bank accounts, fare-capping will expand access to bulk discounts. To take full advantage of this new fare payment mechanism and provide the maximum benefits to New Yorkers, the MTA should permanently implement the fare-capping initiative and expand it to include a 30-day version.

Methodology: We assumed that riders with high incomes can afford the upfront costs of any fare product and choose the most cost-effective pass based on how often they ride. If monthly fare capping were implemented, the ratio of riders using the 30-day pass vs. 7-day pass – regardless of income — would mimic the ratio among high-income riders.

To estimate how many 7-day pass users would benefit from 30-day fare capping, we calculated the ratio of 30-day pass swipes compared to 7-day pass swipes at subway stations in wealthy, high-transit riding tracts. We then applied that ratio to MetroCard swipes in every tract, assuming that the share of riders who would trigger a 30-day bulk trip discount would be the same across the city, leading some current users of the 7-day pass to save from a 30-day fare cap.

We assumed that swipes occurring at subway stations in residential neighborhoods were coming from residents of those neighborhoods. We assumed that 7-day pass users were regular riders on the subway every week each month. We do not think there is a basis to estimate how many single-fare riders or riders using other fare products use the subway regularly, so we excluded them from this analysis.

Cost savings would accrue to other people this analysis doesn’t capture, including bus riders, Staten Island Railroad riders, or riders using non-MetroCard fare products. People who purchase 30-day passes but end up taking fewer rides than the value of the price would also benefit from fare capping and aren’t included in this analysis.

Our projections are based on MetroCard swipes. Under MTA’s fare capping policy, benefits are only available to OMNY users, who make up about 30% of current riders.

Data sources: October 2019, April 2020, October 2021 MetroCard data; 2015-19 American Community Survey, 2019 LEHD data, 2018 MTA New York City travel survey

Per tract, the number of public transit commuters was multiplied by 1.5 to estimate workers and non-workers who take public transit regularly, then adjusted down by the amount that ridership has decreased at nearby subway stations compared to 2019.

In mostly white tracts, less than 50% of residents are people of color. In racially-mixed tracts, 50-75% of residents are people of color. In mostly POC tracts, more than 75% of residents are people of color. Low-income tracts have average household incomes under $40,000. Middle-income tracts have average household incomes from $40,000-$90,000. High-income tracts have average household incomes above $90,000. Commercial tracts defined as tracts where there are at least twice as many jobs as there are residents.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

Transit advocates, organizers, and riders are calling on local and state agencies along with the USDOT to advance projects designed to improve the mobility of Black and Brown individuals at a time when there is unprecedented funding and an equitable framework to transform transportation infrastructure, support the climate, and right historic injustices.

Read More