Arlington County’s CarFreeAtoZ multimodal trip planner is emblematic of local innovation in demand management.

Next week is the annual conference of the Association for Commuter Transportation (ACT), which represents practitioners of transportation demand management (TDM). TDM — which includes information, incentives, and programs that encourage people to use sustainable transportation — is a cheap but effective way to boost transit use as well as biking, walking, ridesharing, and carpooling. It’s typically administered by small, local groups. But federal law looms over the discipline and limits it in important ways. During Tuesday‘s 11 am “rapid fire” session on public policy and funding, my colleague Kirk Hovenkotter and I will present two ways to rethink some of federal law’s influences on TDM.

For one thing, the tax code hobbles efforts to promote sustainable transportation because it allows employers to offer up to $250/month in pretax benefits for parking. (Only $130/month can be used for transit, and just a pittance for bicycle commuting). Our Subsidizing Congestion report finds that this adds up to over $7 billion in annual subsidy for employee parking, and adds over 800,000 cars to the roads every day, mostly in congested cities. The transit benefit helps counteract this, but doesn’t reach enough of the transit-riding population.

Another pervasive influence on TDM providers is the dominance of one federal funding program, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ). CMAQ, which (fittingly) funds projects that reduce traffic and improve air quality, provides the lion’s share of funding for TDM. Most agencies that work on demand management, therefore, define their work in ways that are strikingly similar to the federal government’s guidelines for CMAQ. This leads to a heavy focus on work commutes in congested corridors.

But cutting traffic and improving air quality aren’t the only worthy goals that demand management can accomplish. Smart programs, targeted to the right places, can support economic development and quality of life, and even help build community. Some places are realizing this, reconceptualizing their demand management programs to focus on broader goals. By broadening their definition of what TDM can do, they can often justify the use of broader revenue sources.

For example, Oregon’s DOT has released one of the most progressive documents on TDM we’ve seen come out of a state transportation agency. The department’s Transportation Options Plan doesn’t think of demand management just as a reactive tool for mitigating congestion. Instead, it casts “transportation options strategies” as an integral way to reduce costs for travelers, improve access, and address demographic change in the state. Rather than thinking of TDM as a siloed program, it calls for it to compete on an equal basis with other transportation projects for funding.

Some of the funding for the development of Oregon’s plan came from a Federal Highway Administration grant — evidence that federal policy often works best when it creates a supportive environment for innovation. Even as TDM remains heavily influenced by federal policy, innovation bubbles up primarily from the local level.

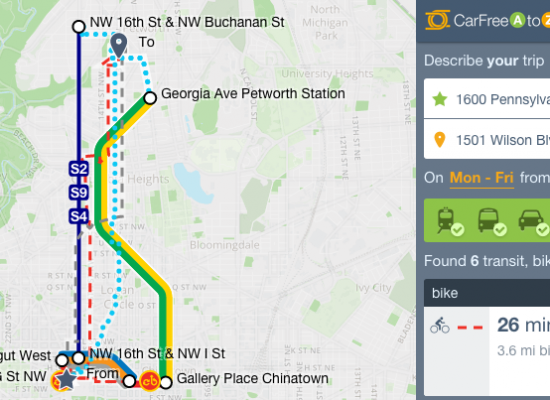

For example, Arlington County (with the help of a grant from Virginia DOT) recently rolled out a cutting-edge multimodal trip planner, CarFreeAtoZ. In 2014, Salt Lake City launched the Hive Pass, a reduced cost monthly transit pass for all city residents. In order to increase housing affordability, Seattle’s DOT may require new multi-family housing developments to offer “residential transportation options programs” that provide residents with transit passes and other mobility options.

If you’re a TDM planner or practitioner, what innovations are you developing? What impact does federal policy have on your work? We’d love to hear. Tweet Kirk and me at @khoven and @shigashide. Better yet, come find us on Tuesday!

The Red Line Project Could Transform Access to Opportunity for Baltimore’s Transit Riders

The Red Line Project Could Transform Access to Opportunity for Baltimore’s Transit Riders

This piece was co-authored by TransitCenter, the Central Maryland Transportation Alliance and Willem Klumpenhouwer, a public transit research consultant. The...

Read More States Are Biased Toward Road Spending. Baltimore Advocates Are Out to Change That.

States Are Biased Toward Road Spending. Baltimore Advocates Are Out to Change That.

A new coalition of environmental, labor, and business leaders is working with elected officials in Baltimore to pass the Transit Safety and Investment Act, a bill currently moving through the Maryland state legislature. The bill would require the Maryland Department of Transportation, which oversees the Maryland MTA, to spend millions more annually on MTA maintenance and operations over the next five years

Read More