As 24/7 operations with an evergreen potential for emergencies, transit agencies have a built-in level of stress that is always on. Photo credit: MBTA

A four-part series on the challenges facing the transit industry’s central office workforce. Part one is here.

By Laurel Paget-Seekins

In order to better understand the state of the entire transit workforce, TransitCenter has been conducting interviews with current and former transit employees about the challenges of hiring, retention, and working in transit right now. A key theme we heard from our interviews with current and former transit agency employees was about stress and burn-out. As 24/7 operations with an evergreen potential for emergencies, transit agencies have a built-in level of stress that is always on. But the transit workforce is at a breaking point because there hasn’t been enough slack built into systems. Interviewees shared that the amount of work they faced was “overwhelming,” they felt both indispensable and unsupported, and “stressed to the point of health damage.”

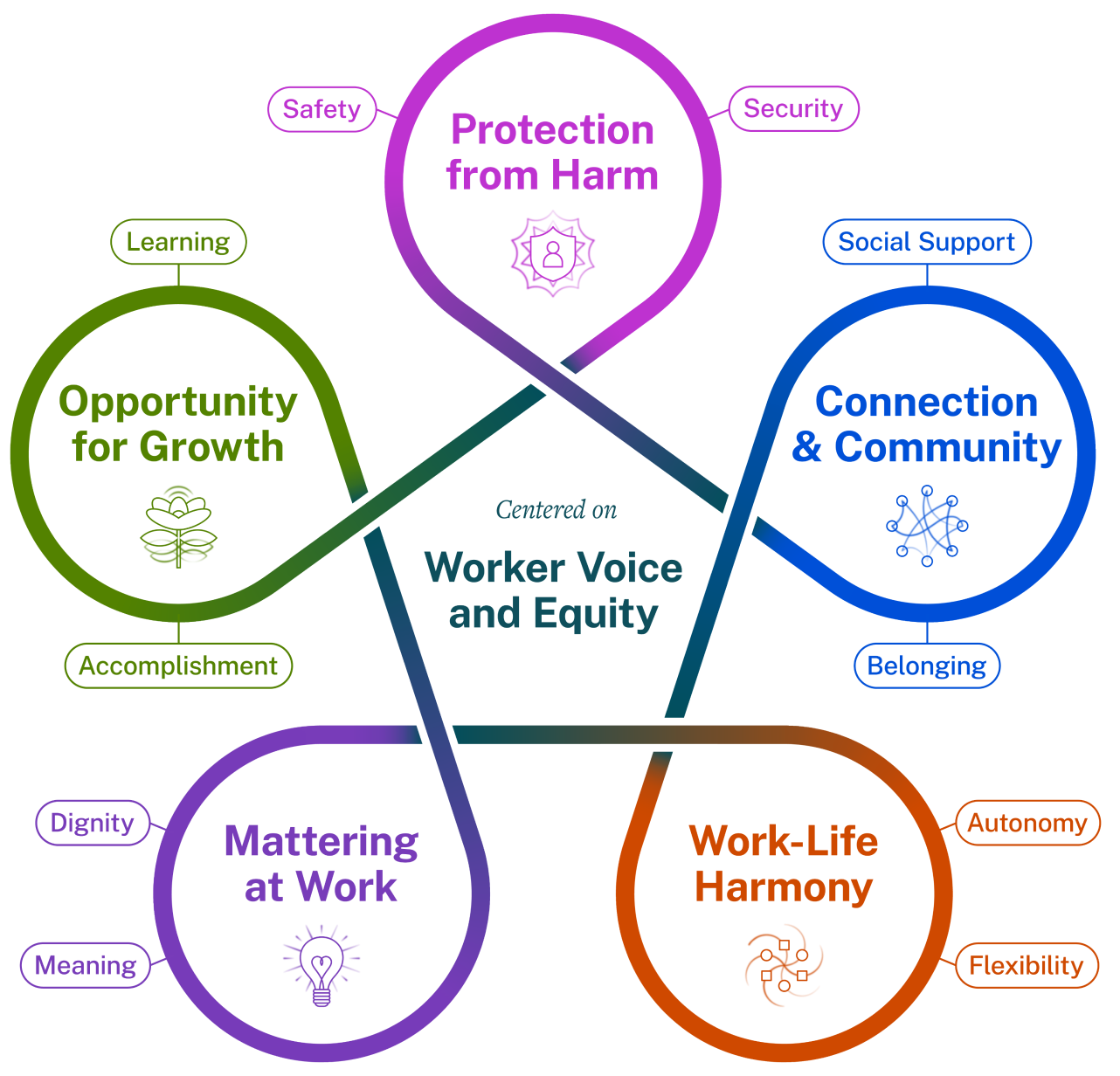

Transit agencies could benefit from taking a look at the Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being framework from the US Surgeon General, which recognizes the critical links between work and health. The framework has five essential components: Protection from Harm, Opportunity for Growth, Connection & Community, Mattering at Work, and Work-Life Harmony. The report speaks to the overall burnout and mental health challenges facing US workers, and was designed to be relevant across industries and roles.

Admittedly, the nature of work at public transit agencies makes some parts of the Surgeon General’s framework hard to implement. Exploring how transit agencies fit into this framework can help us understand the challenges transit workers are having, and what agencies need to prioritize to increase their workplace health.

Most transit agencies are 24-hour operations, 365 days a year. There might not be passenger service at all hours, but agency employees are working around the clock maintaining vehicles and tracks, cleaning, and monitoring the safety and security of people and facilities. Except in extreme cases, agencies operate in all weather or conditions. Even during the initial shutdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic, transit kept running to get essential workers to jobs and to provide access to food and health care.

The 24-hour, 365 day-a-year operations means there is no off-time as an organization. At all times there are people working and people prepared to respond to an emergency or make critical decisions in a short amount of time. At the individual job level, the majority of jobs at a transit agency are safety-sensitive positions. Workers have to be relentlessly attuned during their shifts to keep themselves and the public safe. This carries a physical and mental load. This makes implementing the Surgeon General’s Work-Life Harmony and Protection from Harm both critical and difficult.

Several of the transit employees we spoke with discussed the lack of work-life balance they experienced, and the exhaustion and burnout it causes. A former senior manager with over 20 years experience shared that they felt pressure to put running the service over the well-being of employees, especially during the height of the pandemic. They left their job partially because they didn’t want to be put in that position anymore. Multiple employees reported not receiving the support they needed from their managers or leadership.

Worsening workforce shortages further inhibit agencies’ ability to make space for rest and adaptation. We heard from a senior leader of a small agency who talked about how plans for intentional reflection and long-range planning had to be cut back because managers on their team were out driving buses to keep service going.

In addition, most transit workers are in operations with set shifts and limited autonomy in how their work is done. How work is scheduled is critical to whether these employees have time for rest, and if roles are attractive. The lack of autonomy and flexibility in many transit jobs means that agencies must prioritize Opportunities for Growth for their workforce by encouraging frontline and central office employees to regularly move up and around within the organization.

Protection from Harm includes ensuring psychological safety and operationalization of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) norms, policies, and programs. Employees’ mental health and well-being suffers if agencies do not address racism and other forms of discrimination that can play out in the workplace. The demographics across the transit industry show a propensity for predominately white leadership and management roles and higher concentration of people of color in frontline and operations roles.

While many agencies have committed to addressing DEIA, some interviewees questioned whether that leadership commitment was strong enough to do the significant work of culture change. Some interviewees noted that their agencies had taken steps like establishing employee resource groups, but none of the groups had fundamentally solved the problem. Multiple interviewees stated that fear of retaliation is a problem at their agency and noted that there aren’t adequate processes for addressing complaints and getting employee feedback. One interviewee shared that their female manager was seen as a trouble-maker because she fought for paid parental leave. While some problems that emerged in our interviews can certainly be chalked up to bad management, agencies must strive to create a culture where employees can feel comfortable “rocking the boat.” Increasing collaboration and inclusion in decision-making can also reduce the risk of abuse of power, and improve morale and productivity.

While it is important to see how one’s work serves the agency’s mission, this can cause additional strain on workers’ well-being. People, especially in social service roles, can have negative mental health impacts from internalizing the responsibility of their job and the community trauma they encounter. As transit workers are increasingly on the frontlines of crises for passengers, and as agencies face budget and workforce shortages that impact service levels, the weight of solving large collective challenges should not fall on individual workers.

Multiple interviewees, who had left jobs at an agency, expressed feelings of guilt even though they knew leaving was critical for their mental and physical health. In part, the guilt came from knowing how long it would take to backfill their role, and how much work was left to their former colleagues. Commitment to service without organizational support can mean organizational crises become personal ones.

Moving forward, transit agencies must make deliberate efforts to create time for rest, reflection, and personal and organizational growth. They must make and implement workforce plans with adequate staffing levels and dedicate resources and time for mental health and well-being. Given the inherent challenges of fully implementing Protection from Harm and Work-Life Harmony given the nature of the industry, agencies have to be very deliberate at addressing them; in part by overcompensating in the components of Opportunities for Growth and Connection and Community with robust professional development and inclusive and transparent decision-making. They have to create more balance in Mattering at Work by having redundancy built into schedules and roles so that no one matters too much to take a break.

Laurel Paget-Seekins works in the intersection of data, community, and policy to increase transit equity and quality. She uses her experience as a community organizer, researcher, and an agency employee to strategically champion and implement change. Laurel spent six years at the MBTA/ MassDOT working on fare and service policy, new fare programs, data analytics, performance metrics and tools, and new service pilots. Laurel is currently working with TransitCenter to identify and advance workforce policy changes in transit.