This post was written by Catherina Gioino

In 2021, exhausted Bay Area girls brought their lived experiences of sexual harassment on transit to light through SF BART’s “Not One More Girl” initiative. “Not One More Girl” aims to curb sexual and gender-based violence on transit through a series of education and empowerment trainings that amplify the voices of often marginalized youths.

Initial results from the first phase of the campaign have shown some progress in curbing sexual and gender-based harassment on BART. With the launch of Phase Two on August 31st, BART has expanded the initiative, hoping to foster a culture that genuinely condemns sexism and sexual victimization among its riders in order to ensure safer public spaces for all.

Changing the behavior of riders is an arduous task in a society where sexism remains deeply ingrained, but promising results from the nation’s fifth-largest rapid transit agency’s proactive approach offer a roadmap and a clarion call to other agencies grappling with similar problems.

The genesis of “Not One More Girl”

Girls, defined by BART as gender-expansive youth, created the BART campaign following a 2019 report by the local advocacy organization Alliance for Girls that found 100 percent of the 63 girls surveyed had experienced some form of sexual and gender-based harassment on public transit.

“That felt terrifying,” Alliance for Girls Deputy Director Chantal Hildebrand said after she and her staff convened over the survey results in the ‘Together We Rise’ report. “It was really real because we all recognized that also we [experience harassment on public transit] as adult women. So this research is really what catalyzed a lot of these conversations.”

Following the survey results, the Alliance for Girls held focus groups across the Bay Area and drafted a 12-point policy recommendation plan which they presented to transit agencies across the region– and which proved to be an aggravating process.

“It was definitely frustrating. I think the big thing for agencies was ‘This is a great idea, but we don’t want to pay for it,’” said transportation safety expert Haleema Bharoocha, who served as Senior Advocacy Manager for the Alliance for Girls during Phase One. “Agencies have to invest money internally to combat something so egregious.”

Agencies continued telling the Alliance for Girls that they were committed to combatting sexual harassment but wouldn’t put a dollar amount behind the initiative – except for one. “We went to basically every transit agency, we’re chasing them down,” Bharoocha continued. “BART was the only agency that said, ‘yes, we want to move forward with this.’”

Phases of the campaign

BART launched the first phase of the campaign in April 2021, which included girl-designed materials like posters and a bystander intervention video. BART changed its Customer Code of Conduct to explicitly prohibit sexual harassment and included the creation of a new “non-criminal sexual harassment” reporting category on the BART Watch App, a free mobile app released in 2014 that allows riders to discreetly report criminal or suspicious activity directly to BART Police. Most importantly, BART began collecting data on non-criminal gender-based harassment by asking commuters in a quarterly rider survey if they have experienced sexual harassment on BART in the last six months– a question even BART says isn’t enough.

“We had to at least start getting a baseline set of data. We just have the one question, which isn’t even enough and we’ve made a commitment to do more,” said Alicia Trost, Chief Communications Officer for BART. “We had never been asking the question or collecting data specific to sexual harassment that is not criminal. That’s a really easy first step for agencies to take to at least start to know what the breadth of the issue is, as well as signaling to your riders you care about the topic.”

BART also started conducting surveys to measure the success of the “Not One More Girl” campaign. It found that 52 percent of riders had been educated about the specific effects of harassment on girls, transgender, and gender-nonconforming youth. Additionally, 65 percent of riders were more aware of sexual harassment and gender-based violence as a result of the campaign, and 59 percent would know what to do should they witness harassment.

Thirty-six percent of respondents indicated that the “Not One More Girl” campaign and its policy changes made them feel safer riding BART. However many respondents still conveyed that they didn’t feel safe while on empty trains and platforms. To address this, BART introduced its new “Fleet of the Future” trains on September 11, in conjunction with the start of Phase Two of the campaign, which BART claims will be safer because they are shorter in size and have higher quality cameras.

“By running shorter trains, our scarce resources can be more in places at once, in the sense that if there are fewer cars on a train, they can cover that space much quicker,” Trost said, adding that Phase Two encourages riders to move between cars to deescalate potential incidents and to sit in the first car.

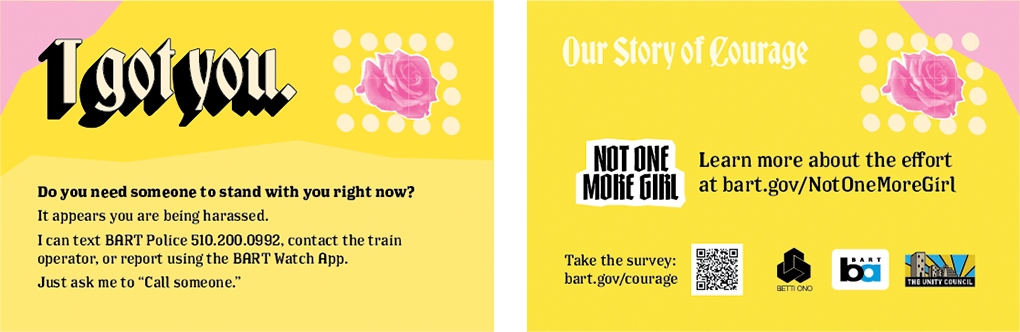

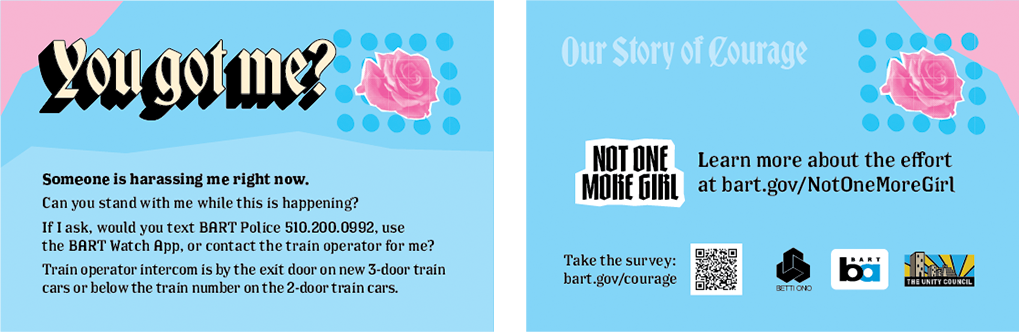

For Phase Two, BART also introduced two wallet-sized cards created and designed by girls featuring slogans like “I Got You” and “You Got Me?” to empower bystanders to play an active role in addressing harassment and promoting safer public transit. “Being able to just hand someone something is something that would be very powerful for [girls] because they often will freeze up in a situation like that,” Trost said about the cards. “The simple gesture of just having a card is something they can take on, and it will also make them feel more of a change agent.” The cards will be available for pick up at each Station Agent booth at BART, and BART Ambassadors and Crisis Intervention Specialists will carry the cards and give them out when engaging riders.

Phase II of the campaign includes cards designed to encourage bystander intervention

In addition to the Alliance for Girls, BART will partner with The Betti Ono Foundation and The Unity Council during the second phase of the campaign to promote incident reporting via the BART Watch app. But this second phase makes an important change. During Phase One, nearly 30 women reported sexual harassment incidents through the app which resulted in the immediate dispatch of officers on the scene. Advocates approached BART after seeing crisis intervention specialists dressing and acting like police, arguing that the response was too carceral in nature.

“When transit agencies are deploying social workers, they have to make sure it’s specifically anti-carceral, that they’re serving people and not replicating what the police does,” Bharoocha said. Fortunately, BART was able to change the protocol and is now using non-policing solutions and language in its job listings, and has since moved to a friendlier uniform for crisis intervention specialists. “Those types of things make a big difference,” says Bharoocha.

Harassment on transit: Global context

Because BART is collecting data about non-criminal sexual harassment, Bharoocha, Trost, and Hildebrand all argue that it has already differentiated itself from most other transit agencies around the world. Only three of the 131 agencies surveyed had programs in place to address sexual and gender-based harassment (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2009). Another study of over 13,000 women across 18 countries found the fear of sexual victimization on public transit significantly hinders women and girls’ abilities to engage in daily activities (Ceccato & Loukaitou-Sideris, 2020). In a more recent study, less than one in six women said they had never experienced sexual harassment on trains.

Transit agencies in other countries have come up with different ideas on how to combat sexual harassment: London enacted a zero-tolerance campaign in October 2021, finding that 63 percent of riders feel more confident intervening when witnessing acts of gender-based violence. A 2020 study in Bogotá found most women were unaware of gender-segregated train cars and buses– the study ultimately showed it failed to reduce harassment. Following a 2014 report that 89 percent of commuters in France had witnessed sexual harassment but didn’t intervene, France launched a 2018 campaign that included bystander intervention signage and better reporting tools.

The impact of “Not One More Girl” and next steps for the campaign

A case study released by the Alliance for Girls on September 13 details the impact the campaign is already having on state policy. California State Senator Dave Min introduced bills SB1161 (to create a street harassment survey) and SB434 (to force public transit harassment data collection). “They were inspired by some of the work that we were able to do from the campaign and brought together and pushed for some state-level power bills,” said Hildebrand.

Overall, the “Not One More Girl” campaign represents what can happen when a transit agency takes a problem seriously and engages deeply with the people who are most affected by it. Advocates and BART employees see Phase One as a productive first step and hope the second phase of the campaign can continue to enhance safety measures. But they know the campaign can only do so much given the pervasiveness of sexism and harassment in American society.

“This is also a conversation that boys and men need to be having– both those people who may be targeted by this issue, but they are also people who are perpetrators of this issue,” Bharoocha concluded. “And really having a conversation on toxic masculinity and the cultural shift that needs to happen to make that shift.”