This post was written by our 2022 research fellow, Kieran Micka-Maloy

As part of our exploration into what our Equity Dashboard reveals about transit access in the seven highest ridership U.S. cities, this blog post takes a deeper look at Washington D.C. In this analysis, we focus primarily on the District itself, rather than the full DMV metropolitan region (the focus of the Equity Dashboard’s Washington DC Story), to illuminate the particularly glaring disparities in access to opportunity via transit within the core city.

Note: The Equity Dashboard is powered by transit schedules and doesn’t capture unscheduled delays, disruptions, or cancellations. The data likely overestimates the access of DC riders at times but gives important insight into how regional transit agencies intended to operate transit service.

WMATA’s continuing struggles

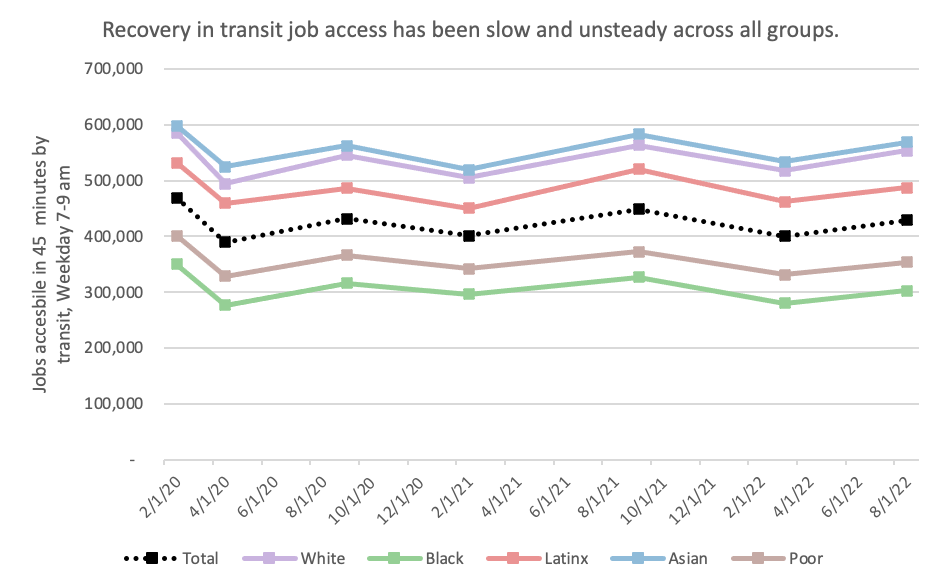

Post-COVID service recovery in DC has been slow and bumpy. In August 2022, Washingtonians could access only 91% of the jobs that were accessible by transit in February 2020. In fact, since March 2020, DC residents have never had a level of transit access equal to before the pandemic. While transit agencies in New York and Philadelphia restored service to pre-pandemic levels months ago, WMATA has yet to reach that baseline.

Furthermore, underlying transit access in DC is inequitable. White and Asian communities consistently have much better transit service than Black, Hispanic, and low-income communities across every tracked metric. This is despite the fact that Black and Hispanic people are more likely to commute by transit – 17% of Black and Hispanic residents of the District commuted on public transit in 2021, compared to only 7% of White and Asian residents.

Access disparities are particularly glaring for Black people living in Washington DC. Black residents are only able to access 55% as many jobs by transit as white residents. The disparity worsened since the pandemic began, when Black residents had access to 60% as many jobs as white residents. (For all dates in this analysis, jobs locations are based on 2017 LEHD data. Changes in job access are due to changes in transportation.) It takes Black residents 28 minutes to reach the nearest hospital by public transit, more than five minutes longer than for white residents.

DC’s transit agency, WMATA, had some high-profile difficulties in 2021 and 2022, which contributed to these issues. In October 2021, a derailment caused WMATA to pull 7000-series train cars from service, requiring the agency to cut rail service by 60%. These cuts dramatically worsened access to destinations for DC transit riders. Our analysis found that between September 2021 and March 2022, access to jobs by public transit dropped on weekday mornings, evenings, and weekends, and transit trips to the nearby destinations got longer. Indeed, in March 2022, jobs accessible on weekday mornings via transit almost matched their March 2020 lows, when service was cut dramatically at the onset of the pandemic.

Turning a corner?

The good news is that since March of last year, things have started to improve for transit riders in DC. Between March and August of 2022, the Equity Dashboard’s most recent data point, service in the District improved across six out of seven tracked metrics, including level of service (which measures the number of transit trips passing through a census block per hour), jobs accessible on weekday mornings (with and without a fare budget) and evenings, travel time to the nearest hospital, and how this travel time compares to auto travel time. Across most metrics, Black and low-income Washingtonians have seen service improve slightly faster than average, but not enough to make an appreciable dent in the large racial disparities discussed in the previous section.

7000-series train cars are slowly being returned to normal service, allowing WMATA to go from running 40% of rail service in January 2022 to 57% in August. According to the Transit Recovery in US Cities dashboard, by November 2022, rail service had returned to 75% of normal levels. Between March and August 2022, Metro announced service increases for buses, the Green and Yellow lines, and the Blue, Orange, and Silver lines. Meanwhile, the Silver Line extension to Dulles Airport opened in November, connecting the airport and fast-growing cities of Fairfax County to transit riders in DC.

To their credit, WMATA and other regional transit agencies have also taken steps to equitably reorient service. Throughout most of 2022, WMATA ran more bus service than it did before the pandemic. In May, Metro bus service was expanded in DC, Maryland, and Virginia. Meanwhile, bus redesigns and service expansion in Alexandria, Virginia and Montgomery County, Maryland have also enabled Washington residents to access more jobs in the suburbs.

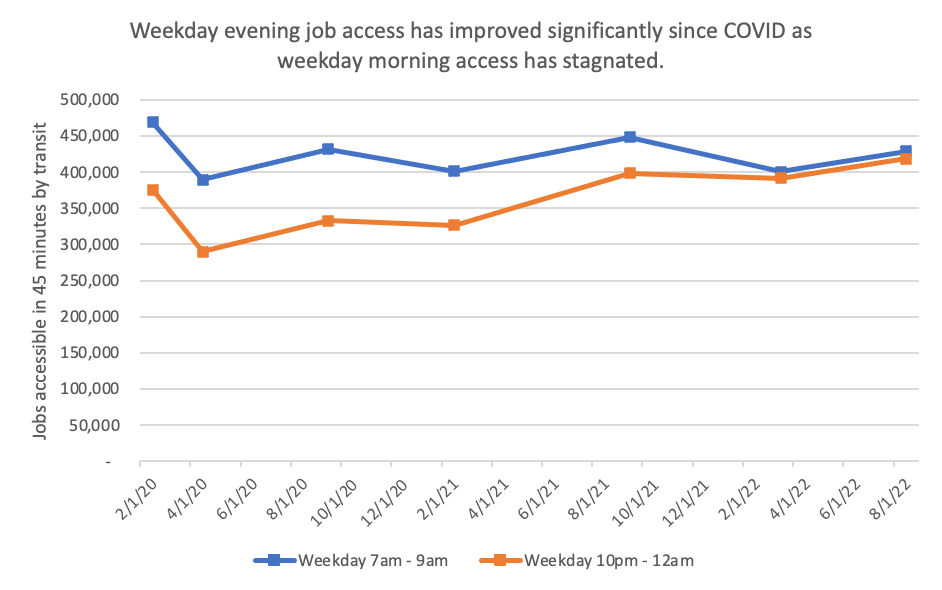

Metro has made a concerted effort to improve service at night, when many essential and low-income workers are commuting. Its Frequent Service network, launched in September 2021, redistributed bus service to run more frequent, reliable service during off-peak hours, including nights and weekends. Metro’s May bus service expansion was designed to add new transfers between routes at night. Rail operating hours were also expanded from 11 p.m. to midnight in 2021.

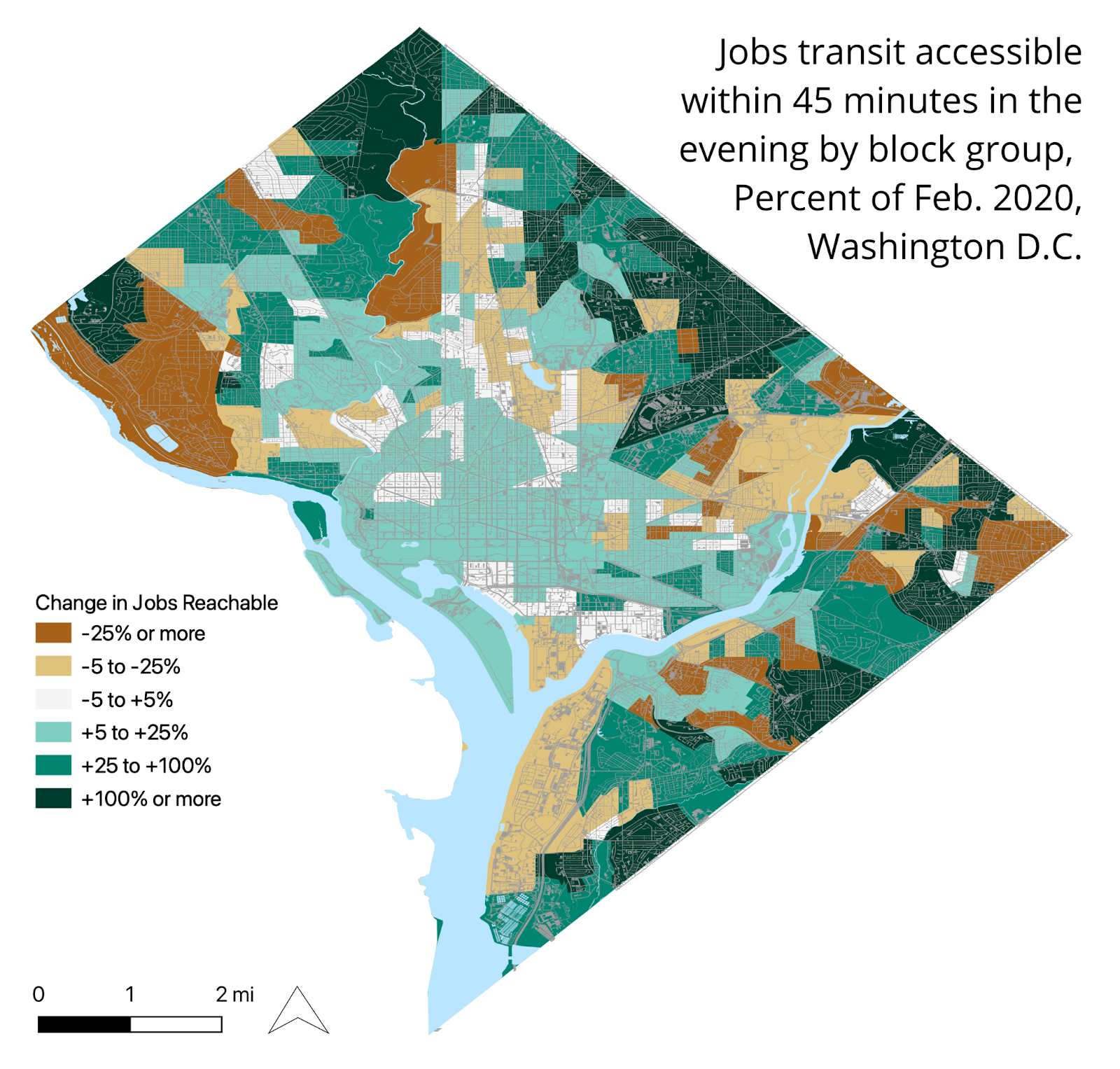

These changes have added up to a big increase in weeknight job access as measured by the Equity Dashboard. As shown in the graph below, commuters traveling on weeknights can now reach 97% as many jobs as those traveling on weekday mornings, compared to only 80% before the pandemic. As the below map shows, much of this weeknight service increase has occurred in outlying DC neighborhoods (as well as in the surrounding suburbs, not shown), which are predominantly low- and middle-income neighborhoods of color. However, the map also shows that certain poor BIPOC neighborhoods have seen nighttime service decrease, such as Marshall Heights on the East Side of the Anacostia River.

An uncertain future

Despite overall improvements to service and equity in the second half of 2022, DC’s transit future is still uncertain. In November 2022, WMATA rail ridership was at 42% of pre-pandemic levels while bus ridership at 82%. Overall, WMATA is on a slower path to transit recovery than New York City Transit, Boston’s MBTA, or Chicago Transit Authority. Furthermore, as pandemic operating support runs out, WMATA is staring down a fiscal cliff that could grow from $185 million in fiscal year 2024 to $731 million in fiscal year 2029. These estimates are based on the optimistic assumption that the system will return to 75% of pre-pandemic ridership by 2029.

To get more people on transit, WMATA and other regional transit agencies will need to tackle DC’s wide and entrenched racial disparities in transit access, providing better service to the Black, Hispanic, and low-income communities that are the core of their ridership. Expanding service on weeknights is a promising start, but not sufficient to meet the challenges of the moment. Bus redesigns and continued schedule adjustments can further contribute to equity and ridership goals in the coming years.

Meanwhile, to tackle the fiscal cliff, regional governments will have to come together to find long-term funding solutions for Metro. Randy Clarke, Metro’s new CEO, has said he “can’t solve the financial problem on [his] own. We’ll either have an aspirational vision for Metro or, without [new] revenue, we are going to have service cuts.”

The pandemic shined a light on transit’s essential role in keeping our cities running, and it’s incumbent upon Washington-area leaders to provide stable, ongoing funding so WMATA can continue serving its vital purpose into the future.