A series of debates in Boston, New York and Chicago are challenging city halls and transit operators to make commuter rail infrastructure within the city limits part of the transportation answer in both booming and struggling urban districts. In this post, we look at Boston’s Fairmount Line. In a 2017 Streetsblog article, transit expert Alon Levy said the line could be a national model for converting a low-frequency suburban line to rapid urban rail service. The transformation was partial at that time, and unfortunately, little development has happened in the intervening two years.

The good news is that strong interest by the City of Boston, advocates and surrounding communities abides, but it may be that the further investment in the line will await a state administration more interested in transit improvement and focused on urban areas.

Fairmount Line runs mainly within city limits, and potentially fills the rail void in southern Boston between the Orange and Red Line subway routes created when the Orange Line was moved to the west in the 1980s. Environmentalists negotiated the line’s transformation as part of the mitigation package for the traffic-increasing effects of Boston’s Big Dig highway project during the 1990s. In the 2000s, old stations were rebuilt and new stations added along with upgrades to track and signals. As a result of these changes, and a reduction in fares, ridership nearly tripled from 2012 to 2016 (though remains very low for urban rail, at 2,300/day in 2016).

The Big Dig negotiation used as its basis the findings of an earlier city (Boston Redevelopment Authority) planning initiative that called for a more thorough transformation of the Fairmount line, including use of more agile self-propelled train cars to allow for much greater service frequency, and integration of fares with the rest of the urban system via MBTA’s Charlie Card. Today the line uses the same vehicle set-up as longer-range MBTA commuter lines, with locomotives pulling or pushing unmotorized passenger cars. Levy’s piece and a report by the Boston Foundation lay out in detail the rolling stock and frequency issues, including very poor peak hour headways, and the problem of not integrating fare payment with connecting bus and subway lines.

The Patrick administration in fact ordered diesel multiple unit trains for the line, but new governor Charlie Baker canceled the order in 2015, in one of his first acts in office. Today the MBTA and state seem more interested in using the line to extend low-frequency service deeper into the suburbs rather than in further building the line’s urban utility. Last summer, the MBTA control board voted to fund a pilot extension of regular commuter service to a part-time station now used primarily for New England Patriots football games at their outer-suburban stadium.

Advocacy to improve the line’s urban segment continues. A recent TransitMatters report on the future of MBTA commuter rail service presents electrification and other improvements along the Fairmount Line as low-hanging fruit. Mayor Marty Walsh’s 2017 GoBoston plan calls for a “phase 1” of improvements including better walking and cycling access to Fairmount stations, more frequent trains and CharlieCard integration, though it’s hard to know how the city will pull off a better schedule and fare transfers without a major contribution of capital. A city-led low-cost “pilot” has been mentioned in recent news stories, but without any clear description.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

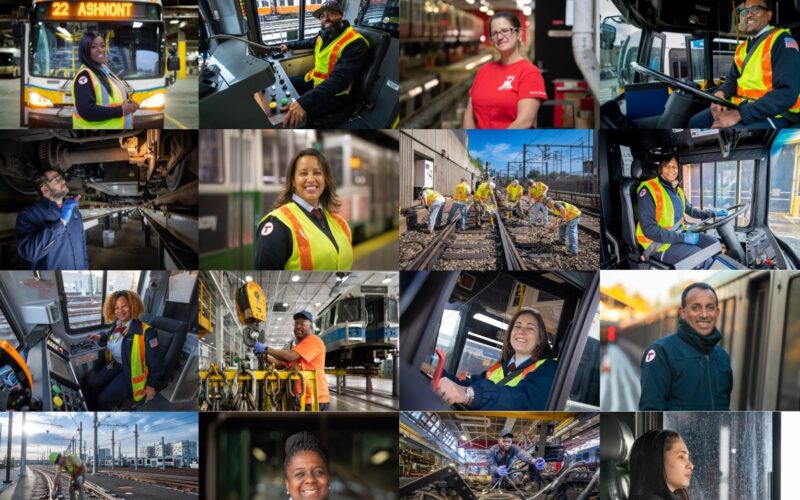

Read More MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and its union, Carmen’s Local 589, reached a historic agreement to increase bus operators' starting wages from $22.21 to $30 an hour, shifting MBTA operators from the lowest paid to the highest paid in the transportation industry.

Read More