This Ridership Initiative guest post, by AC Transit Transportation Planner John Urgo is our latest from transit agency staff working to understand and respond to declining ridership in their system. AC Transit is among the growing list of transit agencies experimenting with expanded on-demand transit service. This piece describes the launch of on-demand service in lower density areas as a trade-off for focusing traditional bus resources in potentially higher-ridership areas. If your agency would like to share its story or if you would like to hear from a specific agency or about a particular topic, let us know by emailing ridership@

In July 2016, the Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District (AC Transit), which provides bus service to 13 cities and unincorporated areas in San Francisco’s East Bay, launched an on-demand transit pilot as part of an effort to address declining ridership, improve service quality, and redesign our network in low-density, low-demand areas.

Like many transit agencies around the country, AC Transit has seen ridership decline in recent years, but the declines have not been spread evenly across our district. In denser areas, including the cities of Oakland and Berkeley, ridership has fallen 3% since 2013. In less dense cities like Fremont and Newark, ridership fell 20% over the same period.

Our pilot aimed to test whether in sufficiently low-density service areas, on-demand service could improve service quality at an equal or reduced cost, freeing up resources that could be invested in a higher-frequency fixed-route network. On-demand transit cannot carry as many passengers as fixed-route transit service, but it can still be a powerful transit planning tool. Using on-demand transit to preserve transit access in low-density areas will allow us to bring higher-frequency fixed-route transit to more riders in those same areas.

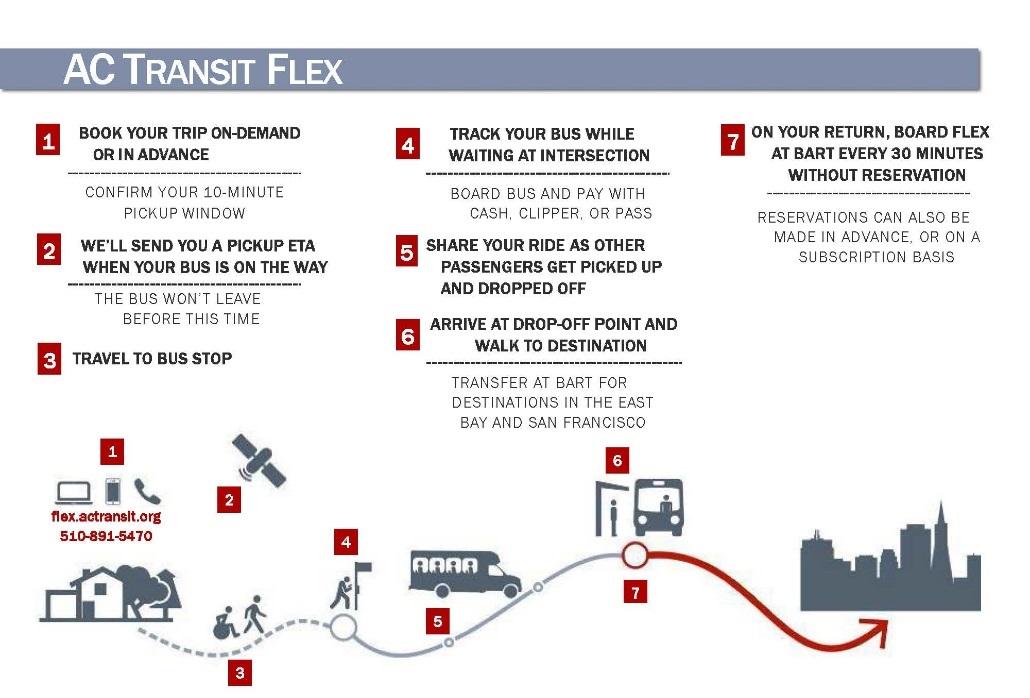

Our “AC Transit Flex” service launched in two zones—one as a replacement for a fixed route and the other as an overlay of existing service—allowing customers to book trips on-demand, in advance, or on a subscription basis from select bus stops using any internet enabled device or the District’s customer service call center. There is no fixed route or schedule, except at the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) stations within each zone where passengers can board at scheduled times without a reservation, notifying the operator of their destination, who enters it on a tablet computer running scheduling software developed by DemandTrans. The fare is the same as a local bus, all of the 16-passenger buses are wheelchair accessible, and all on-demand buses are driven by AC Transit’s union operators.

We aimed for the pilot to be cost neutral, swapping the service hours used on the discontinued fixed route with the hours needed to run Flex. And while service hours are the primary cost, the use of smaller buses did eke out a savings large enough to cover the added cost of the software. This was due to lower vehicle operating and maintenance costs per mile, and fewer miles driven (which was in turn due to direct routing enabled by the scheduling software, but also to fewer riders—more on that later).

After a year of operation, Flex has achieved some success. Over 700 customers tried it, completing 23,000 trips and returning 70 percent of the time after taking their first trip. On-time performance improved, even though operators now drive a different route every hour. We increased frequency at the schedule point—the BART station—where two-thirds of passenger trips begin or end (thanks to the bus serving only requested trips). And, people liked it: 94 percent of riders surveyed preferred Flex over restoring the fixed route, and 70 percent said they would take AC Transit more if the service were expanded.

Flex’s successes have depended on a focus on providing equitable access for low-income riders, people with disabilities, and those with limited English proficiency. This means not only providing wheelchair accessible vehicles for every trip, but incorporating booking and payment methods for customers without smartphones or bank accounts, including translation services at every step of the process, and offering a range of trip options, from on-demand, scheduled, and subscription to walk-on. More access and trip options simply means more trips can be booked into the system.

But by other measures, Flex has not performed as well. Just 3 passengers per hour use the service on average, which is less than half of the fixed route it replaced. Partly this stems from the reservation barrier. For example, 40 percent more trips begin at the BART station (where passengers can board without a reservation) compared with trips that end at BART, which would require a reservation. Some passengers prefer not to make a reservation and instead to take whatever service comes first; but this may also suggest a need for more education and outreach from AC Transit.

Around seven passengers per hour use the service during peak periods (about the maximum we hope to achieve), but there’s no getting around the fact that on-demand transit carries fewer passengers per hour than even a low ridership fixed route. This makes it hard to justify as a replacement service, especially on a route for route basis. So why is AC Transit planning to expand Flex throughout Fremont and Newark?

To borrow a concept from transportation consultant Jarrett Walker, transit agencies have dual and often competing goals of “coverage”—ensuring everyone, particularly those in need, have access to some transit service—and “frequency”—investing in service levels that make taking transit convenient and useful to more people.

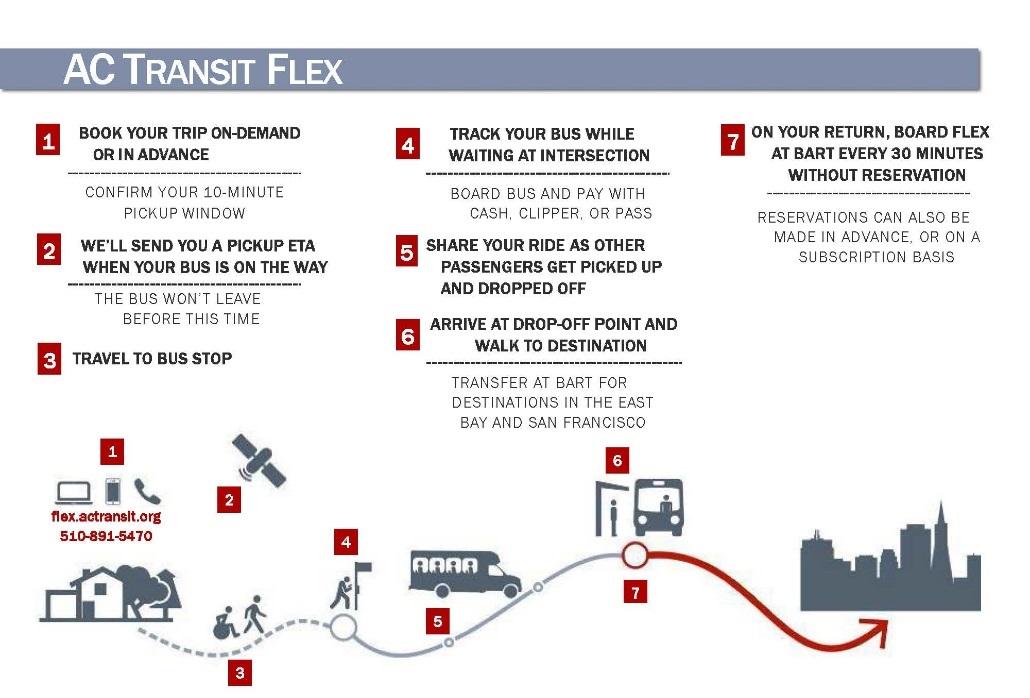

AC Transit’s current network in Fremont and Newark, consisting of 6 hourly routes and 4 running every half hour, is 100 percent coverage service. These routes are stuck in a vicious cycle: low ridership means we run less frequent service which results in lower ridership. The network carries an average of 14 passengers per hour (half of AC Transit’s network-wide average); requires eight percent of resources but generates just four percent of total ridership; and ridership continues to decline.

With the new network, being developed with input from city partners and the community, AC Transit hopes to make this cycle virtuous: service hours would be reinvested in frequent service on a smaller number of key corridors, while five to seven Flex zones anchored at major transit centers would provide bus stop to bus stop coverage service everywhere else. The plan would shift resources significantly, from 100 percent coverage to a 70 percent ridership–30 percent coverage split, at the same operating cost as today.

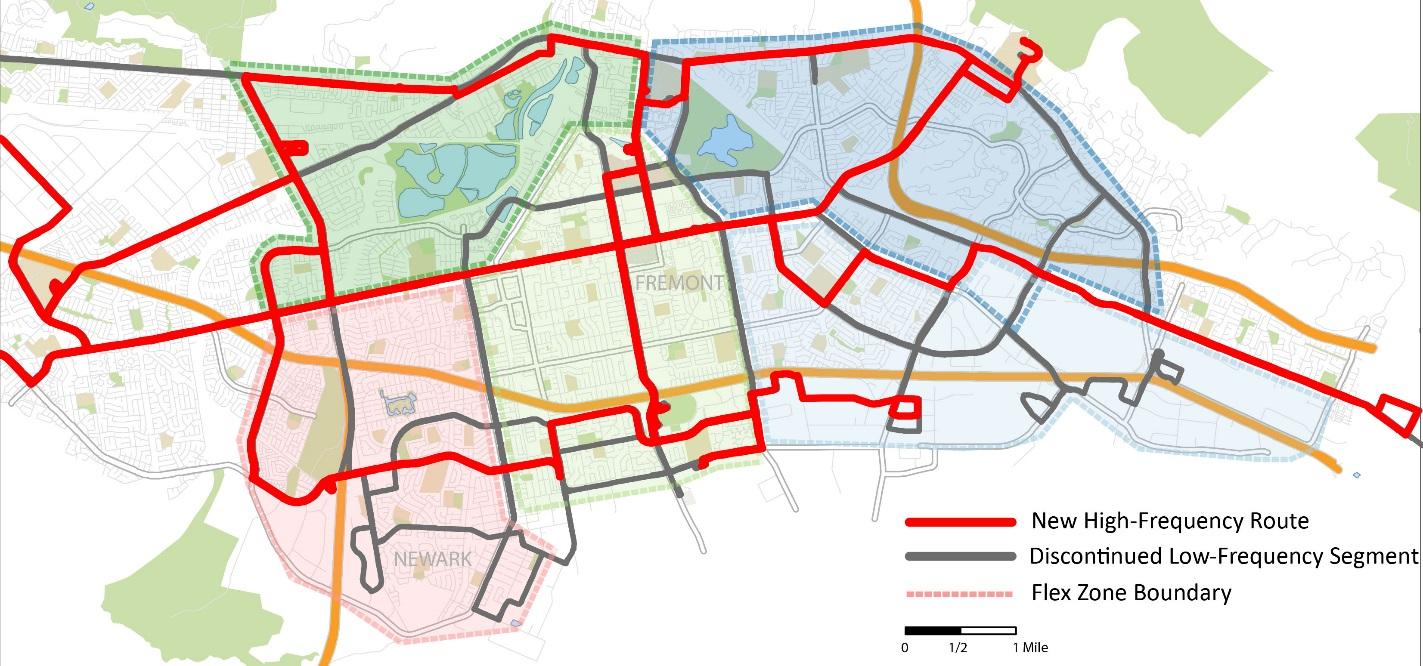

How well this new network performs will depend on the new fixed-route network, which could see two to four times as much service. If these higher-frequency routes carry 22 passengers an hour—the level of the best performing route in the area today—ridership should grow 11-20 percent. If the new routes merely maintain the current average of 14 passengers per hour, ridership will decrease.

The proliferation of publicly provided on-demand transportation—whether in the form of dial-a-ride, subsidized ride-hail trips, or autonomous vehicles—has drawn a lot attention of late. These services could support a robust transit and transportation network. Or, they could lead to unequal transportation options, increase emissions and congestion, and continue to shift transit labor to the gig economy.

If tackling declining ridership is the goal, it makes sense to invest in the things that make transit more useful to more people—fast, frequent, reliable service. This is also what transit agencies can do best, and it’s why 70 percent of operations funding in our planned Fremont and Newark network will be invested in fixed-route service. But Flex will also play an important role. As we expand the service we’re being clear about its goals, setting realistic expectations for productivity and prioritizing accessibility and equity. By doing so, we think we can provide more of our riders better service at the same operating cost.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Thanks to Riders' Alliance successful #6MinuteService campaign, New York City subway riders will enjoy more frequent service on nights and weekends, starting this summer. In this post, we chronicle the group's winning strategies and tactics.

Read More