Photo credit: Maryland Sierra Club

As we wrote last year after the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (or “bipartisan infrastructure law”), the IIJA could advance climate and equity, or could continue to entrench environmental injustice in the transportation system.

Programs administered by the Federal Highway Administration make up the largest chunk of surface transportation funding in the IIJA. The good news is that most of this funding is flexible – it’s not restricted for use on roads and can be spent on public transportation projects, as well as pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure.

The potentially bad news is that these programs are largely controlled by state governments, putting those key decisions in the hands of state department of transportation heads, governors, and legislatures (and to a lesser degree, municipal leaders). Many of these entities (especially states) do not have a history of prioritizing transit. Without advocates making noise at the state level around this issue, we’re likely to see a continuation of road building, locking in decades of future emissions.

It’s critical now for advocates to focus on creating a vision for what transit should look like at the state-level, and to share that vision with their elected leaders and staff at State DOTs. Regions also have the ability to flex some of this funding, so advocates should simultaneously develop a city-level vision and target their mayors.

How the funding flexibility works:

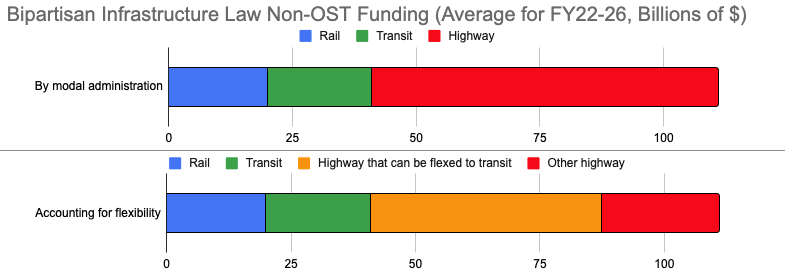

The majority of the funding in the bipartisan infrastructure law is administered by the Federal Highway Administration and controlled by states, and to a lesser degree, metropolitan planning organizations. The bulk of this “highway” funding is multimodal and can be spent on transit, biking and walking. The orange bar represents the National Highway Performance Program, Surface Transportation Block Grant Program, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality, and Carbon Reduction Program–the four largest flexible programs. (This chart accounts for money administered by the FHWA, Federal Transit Administration, and Federal Rail Administration. It does not include grants provided by the Office of the Secretary.)

Four of the largest federal highway programs are flexible:

- Funding from the National Highway Performance Program (NHPP, the largest federal formula program, which primarily funds Interstate highway projects) can pay for transit near a highway, if a cost-benefit analysis shows the transit project would be more cost-effective than expanding the highway.

- The Surface Transportation Block Grant Program, the second-largest highway formula program, can be spent on transit infrastructure without any additional requirements. The same is true for the new Carbon Reduction Program. States control most funding in these programs but substantial amounts have to be spent in large metro areas, where and the metropolitan planning organization plays a major role in deciding how money is spent.

- The Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality program (which can fund projects only in areas where air quality violates EPA standards) can also be used for transit. The implementation of CMAQ varies by state, but MPOs often play the lead role in deciding how to spend funding within their boundaries.

There is also a second form of flexibility, which is that up to 50 percent of many federal highway programs can be moved into another program.

An obvious case for initiating this flexibility is in Colorado, where the state department of transportation recently admitted that long-standing plans to widen I-25 through downtown Denver were fiscally unrealistic. Meanwhile, staff at Denver’s Regional Transit District have indicated that the agency is facing significant funding shortfalls, and has limited or no capacity to grow rail or bus services. Colorado could potentially use its federal highway funding as a new revenue source for transit, tapping NHPP funding to improve the rail lines near I-25, or to build bus priority projects nearby. Or, it could transfer money out of its NHPP allocation into other programs, and use those for a broader investment in transit.

The U.S. Department of Transportation recently published a resource outlining which programs are flexible, describing the administrative process for “flexing” federal highway dollars, and referencing real-world examples of where programs were used for transit, such as a Texas project to improve sidewalks near bus stops and a Connecticut project to install secure bike parking at a train station.

It’s fantastic to see an official resource acknowledging the flexibility of federal funds. However, the USDOT resource focuses on small projects that improve access to transit. It is critical to note that hundreds of billions of federal transportation dollars can be flexed from roads to transit, and they can pay for transit projects themselves–not just projects to improve access to transit.

In the Chicago region, the Chicago Metropolitan Area for Planning plans to transfer over $300 million in federal highway funds so that the CTA can improve two rail stations downtown, and make a third station accessible to people with disabilities. In 2019, New York state announced it would use $14 million in federal highway funds to pay for transit projects like bus rapid transit near Albany, new buses for the Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority, and expanded transit service in the Syracuse region.

Advocacy and Legislative Leadership

And yet this flexibility is for naught if state governments don’t choose to use it. As the USDOT points out, a state department of transportation has to initiate the process of flexing funds. State decision-makers are unlikely to do so unless presented with an expansive vision for transit – something worth flexing highway money toward.

Two successful recent examples of this in practice involve advocates pushing for state legislative mandates for increased transit spending.

In Maryland, advocates like the Central Maryland Transit Alliance helped convince lawmakers to take control of the state’s transit agenda after Governor Larry Hogan canceled the Red Line rail project in Baltimore. Last year, the legislature mandated that the state spend at least $400 million annually on public transit maintenance and repair, overriding a gubernatorial veto to do so. This spring, they overrode another veto and passed a law requiring the state to hire staff and plan to expand the MARC commuter rail system. More recently, they passed laws requiring the state to examine new models for transit governance in Baltimore and to advance the Red Line.

In Massachusetts, the advocacy group TransitMatters helped convince state lawmakers to amend climate legislation to include a requirement that the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority plan to electrify its commuter rail lines. TransitMatters believes this would improve air quality and enable faster service, which it views as necessary for a broader transformation of the network into regional rail.

Neither the Maryland nor Massachusetts legislation identifies specific funding sources, but flexible federal funding is an obvious way they can meet these mandates.

An emerging example of influencing city officials to use IIJA funds for transit comes from Pittsburgh. Advocacy group Pittsburghers for Public Transit issued a “100 Day Transit Platform” when recently-elected mayor Ed Gainey took office, much of which ended up reflected in recommendations from the mayor’s transition team. Now, the group has called on Gainey to keep his promises by using IIJA funding for new bus shelters and stop amenities, safe and accessible pedestrian connections to transit, and planning grants for equitable transit-oriented development.

Changing the funding paradigm at the state and regional level will require upending business as usual. But it’s our best shot at getting positive outcomes from the IIJA – cleaner air, expanded and more reliable transit service, and safe and dignified places to wait for a bus, walk to the store, or bike to school.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

To Achieve Justice and Climate Outcomes, Fund These Transit Capital Projects

Transit advocates, organizers, and riders are calling on local and state agencies along with the USDOT to advance projects designed to improve the mobility of Black and Brown individuals at a time when there is unprecedented funding and an equitable framework to transform transportation infrastructure, support the climate, and right historic injustices.

Read More