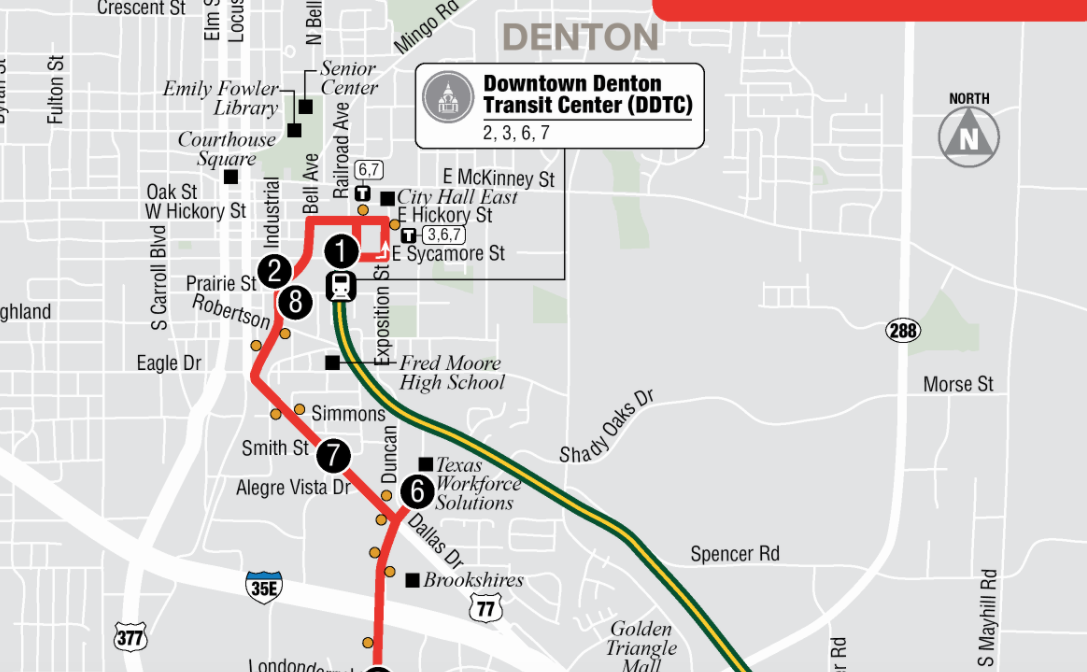

One of six bus routes on the chopping block in Denton, Texas. Image: DCTA

Despite mounting evidence of the limits of microtransit, the transit agency in Denton, TX, is barrelling ahead with a plan to replace most of its fixed-route bus system with on-demand service.

If the so-called “GoZone” proposal – which the Denton County Transit Authority’s board gave initial approval to in April – goes forward, then on-demand vans operated by Via are expected to replace six out of DCTA’s eight local bus routes, as well as its express bus service. The agency’s existing commuter rail service to Dallas and shuttle bus service for the University of North Texas will remain unchanged.

DCTA leadership claims that Via’s zone-based, on-demand model will result in reduced wait times for riders, an expanded service area, and more hours of service, all while saving the agency $2.6 million a year. But other experiments in microtransit – Innisfil, Ontario; Pinellas County, Florida; and Los Angeles – serve as cautionary tales. Outsourcing fixed-route transit functions to microtransit companies has not panned out well for riders or workers. Nor does it usually turn out to be the fiscal bargain it was promised to be.

While DCTA is a small transit system in a modest-sized city, the decision could have far-reaching impacts. Giving microtransit a foothold as a replacement for most of a city’s fixed-route buses has major implications for the quality of service and labor rights. Other smaller transit agencies will no doubt be paying attention to this example.

Established in 2002, the DCTA serves Denton County in North Texas’s Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. Its routes primarily operate in and between three municipalities: Denton, Lewisville, and Highland Village, all of which contribute a half-cent sales tax toward funding the agency. In 2019, DCTA’s fixed-route bus system carried almost 2.5 million trips, averaging around 17 trips per hour. According to the agency, the fixed routes slated for changes or elimination carry 10 or fewer people per hour (though it’s unclear whether these numbers include 2020, which should be considered a statistical outlier due to the pandemic).

The pitch for GoZone is that it will improve service and the rider experience, making DCTA a model for similarly-sized agencies. Rather than walking to a bus stop, riders would book a trip through the DCTA/Via app and then walk to a designated pick-up location, which the agency says will include most street corners. The service’s first phase includes two primary zones — one in Denton and another in Lewisville and Highland Village. In the future, DCTA “plans to expand those zones and create new ones.”

Riders would be able to book GoZone trips as early as 5 a.m. and as late as 10 p.m. most weekdays (extending to 11 p.m. on Fridays), compared to current bus service that begins at 6 a.m. at the earliest and runs until 9 p.m. at the latest (most routes operate between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. during the week). Saturday service would likewise be available until 11 p.m. instead of 7 p.m. Summoning a GoZone ride would purportedly reduce wait times compared to the typical 30-50 minute headways on bus routes.

But thousands of riders’ daily mobility needs may soon hinge on a dubious business model that has performed poorly in other places. The promises of cheap fares, shorter waits, and lower costs only hold up when few people use the system and transit workers are devalued.

GoZone can’t scale

For the first six months of GoZone, fares would cost only 75 cents, half the current price of a transit ride on DCTA. After the promotional period ends in March 2022, DCTA staff and the board of directors plan to reevaluate the fare system and make changes if needed.

Other agencies that have replaced fixed route service with on-demand service have run into difficulty sustaining these “promotional” fares. Unlike fixed-route transit, which requires less subsidy the more riders it attracts, the costs of on-demand service rise along with ridership. When Innisfil, Ontario–a Toronto exurb of about 37,000 residents–partnered with Uber in 2017 to provide subsidized trips, the city’s transit subsidy grew from $150,000 in 2017 to $640,000 to $900,000 in 2019. The city was forced to limit each person to no more than 30 trips per month to curb the ballooning budget.

As transit expert Jarrett Walker remarked, “For a transit agency, [a service like Uber] works best when not very many people are using it. Because when people start using it in any numbers, it devours the entire budget.”

In Pinellas County, Florida, a similar experiment replacing low-ridership bus routes with subsidized Uber and taxi rides was also underwhelming. Ridership was negligible, prompting the transit agency to lift most geographic restrictions on usage of the discount, which made it impossible to tell whether the subsidies were helping people replace bus trips or pay for cab rides they would have taken anyway. Even then, ridership never exceeded 100 trips per day.

The truth is that despite the purported “user experience” benefits of microtransit, the model hasn’t proven especially popular with riders in American cities. When the Eno Center for Transportation analyzed two mobility-on-demand pilot projects in the Puget Sound and Los Angeles regions, they found that neither managed to exceed an average of four trips per hour (3.94 and 2.61, respectively) and topped out at only 7.48 and 3.45 trips per hour in the peak service period, respectively. In LA Metro’s case, the agency increased the per-passenger subsidy for its on-demand service in a hail mary attempt to attract riders, diverting money away from more productive routes.

For DCTA, much of the GoZone’s potential savings would come from reducing labor costs, at the expense of the agency’s contracted workforce. DCTA currently contracts with North Texas Mobility Corporation (NTMC) to employ about 80 bus operators and other workers. It’s assumed that as many as half or more would be laid off as a result of the changes. Though the agency says employees will have priority in reapplying to work for Via, the current starting pay of $17.50 per hour could be more than halved to $8 per hour.

Mobilizing for better service than microtransit

Staving off GoZone will be an uphill fight, with the DCTA board scheduled to vote on final approval of the Via contract on July 22.

Some Denton City Council members have argued against the proposal, with several stating in June that DCTA had advertised it as a pilot and not a near-irreversible system overhaul. That month, the City Council voted against renewing a city contract with Bird Advocacy & Consulting, the transportation consulting group thought to have championed the on-demand model to the DCTA. And this week, in a 5-2 vote, the City Council approved a resolution advising the DCTA against proceeding with the GoZone proposal.

But due to DCTA’s regional governance structure, which gives outsized representation to suburban interests, the City Council is limited in its ability to stop the DCTA from going forward with the changes. Of the five voting members on the DCTA board, only one is nominated by the City of Denton, which contains the vast majority of the area’s current and potential transit riders.

Denton-area transit advocates have recently formed No Bus Cuts Denton to organize against the proposal, but the group will need additional time to raise alarm.

ATU International may file a grievance pertaining to Section 13(c) of the Federal Transit Act, which places restrictions on using federal funding to undermine mass transit employee protections. Even if unsuccessful, the grievance could slow down the GoZone proposal enough for Denton City Council to appoint a new DCTA Board Member and give advocates a fighting chance to organize against it.

Advocates have pledged that once they conclude their campaign to preserve bus service from the current threat, they’ll focus on improving it. Experience from New Jersey to New Orleans suggests that shining a spotlight on the DCTA board and reforming its structure may be instrumental to winning better service.

If nothing else, microtransit is aptly named. Ridership will always remain tiny with microtransit, because the service is, by definition, preposterously expensive to scale up. And microtransit is typically tied to a business model that shrinks wages and benefits for transit workers. It’s a small-time solution that may have limited value in niche cases. But if Denton, or any other city, aims to provide better service for riders, build a strong transit workforce, and draw more people to transit, improving fixed-route service is the way to go — microtransit just can’t deliver.