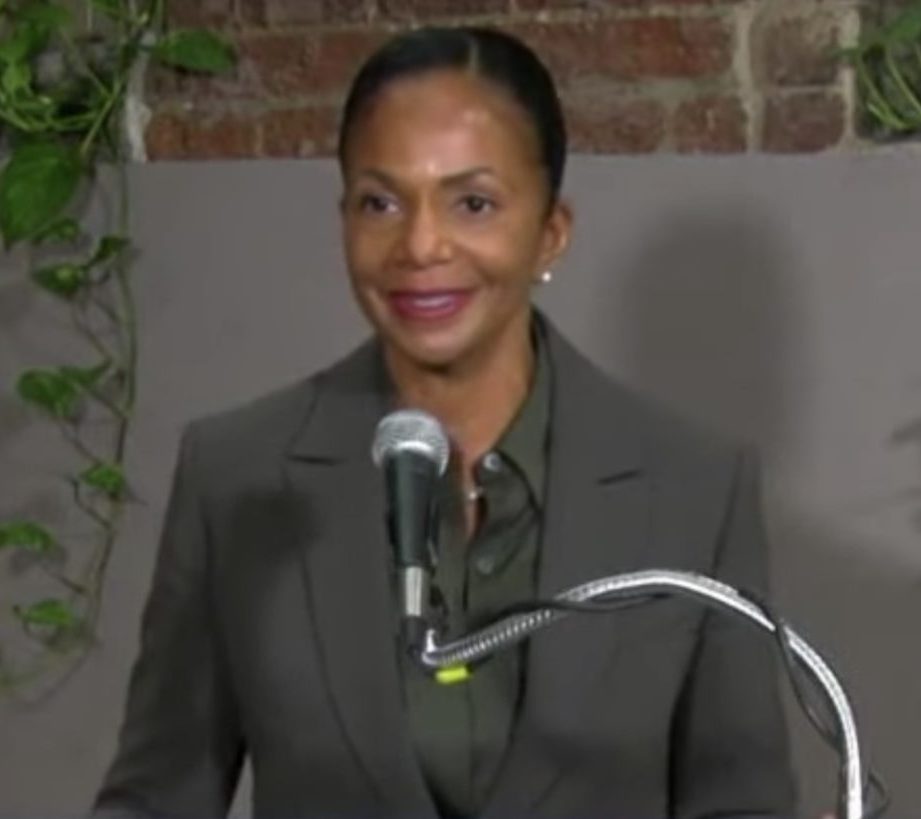

When Debra Johnson took the job of General Manager and Chief Executive Officer of Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD) in November, she signed up to steer the agency through multiple crises.

RTD had been on a troubled path before the COVID-19 pandemic, after years of ridership decline, labor-management turmoil, and a credibility deficit with riders. Johnson, the first woman to hold the top leadership post at RTD, and the first CEO since 1995 to be hired from the outside rather than promoted from within, brings a fresh eye and a multi-city resume that’s relevant to RTD’s challenges. In her first few months, she’s publicly signaled a willingness to address problems that have festered too long at the agency.

The Denver region needs three things from its new transit chief: one, a commitment to operations, especially delivering more and better service to the riders who use and need transit the most; two, guiding what has been a fragmented board of directors to more productive decision-making; and, three, being frank with the board and the community at large about where and how RTD can be most successful, given its expansive service area and finite fiscal resources.

A new commitment to operations that serve riders today

Johnson comes to town with a strong background in transit operations. As deputy general manager of Long Beach Transit, she was directly responsible for all operations for a system providing 23 million trips a year. Prior to her six years running operations at Long Beach, she was deputy chief operating officer at L.A. Metro.

Johnson’s experience running day-to-day service represents a change for RTD leadership. Since 2004, the agency has focused above all on FasTracks, a multi-billion dollar effort to build light rail to Denver’s farflung suburbs. Throughout the FasTracks era, RTD has functioned more like a construction company than a transit provider intent on running good service for riders. Ridership on RTD has declined steadily since 2014, and the number of jobs accessible within a 30-minute transit commute hasn’t budged, despite billions spent on FasTracks.

Johnson has spent her first few months in Denver in the garages and out riding the routes, talking with RTD employees. She’ll need to build mutual understanding to improve the rocky labor/management relationships of the past few years. Before the pandemic, RTD struggled to retain bus and train operators and faced a constant labor shortage that disrupted service. Now COVID and the resulting recession have hit the workforce with the one-two punch of health risks and job insecurity, with RTD recently pivoting to considering layoffs during the pandemic.

A stint earlier in her career as chief labor negotiator for San Francisco Muni should serve Johnson well at RTD. At Muni, she sat across the table from TWU Local 250-A, in the big leagues of transit labor relations. San Francisco sources told the Denver Post that Johnson earned a reputation as a tough but fair negotiator.

Guiding the RTD board to more productive decision-making

Making RTD more responsive to riders will require marshalling a cohesive vision for successful transit among a politically fragmented board of directors.

The RTD board, directly elected in 15 districts across a region of 2,342 square miles, has generally functioned as an assemblage of territorial interests rather than a collective. This parochialism feeds into RTD’s emphasis on far-flung expansion to low-ridership areas and neglect of high-ridership areas. Based on its past track record, the RTD board of directors as a whole may be resistant to prioritizing ridership, or even weighing trade-offs fairly.

Fortuitously, Johnson’s career includes up-close and personal experience with a fragmented board, during her time as authority secretary to the board of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transportation Authority (WMATA). The WMATA board is a multi-headed hydra of appointees from multiple municipalities, two states and the District of Columbia, and the federal government. Johnson will need to draw on that experience with a fractured board to inspire some cohesion among the RTD board members.

Define a realistic vision for the post-FasTracks era

In her first major statement in her new role, Johnson told APTA’s Passenger Transport magazine that RTD needs to “optimize our services for the betterment of those who are most dependent on transportation.”

This bodes well for the “Reimagine RTD” planning process. Launched before the pandemic, “Reimagine RTD” was originally intended to guide the agency’s board to make tough choices about concentrating service where it is used and needed most, and correcting the agency’s past tendency to prioritize far-flung, low-ridership routes. The pandemic scrambled long-range planning, but some interim steps to prioritize ridership hint at progress.

Johnson seems prepared to deliver frank truths about trade-offs and decisions about resource allocation, even if it means telling people things they don’t want to hear. “Governing during a pandemic is not a popularity contest,” she told Passenger Transport. “I’d rather be respected than liked,” she told us. To be successful in the role, she’ll likely need to say some unpopular things. Without a personal stake in past projects, it may be easier for her to take a hard look at what hasn’t worked historically, and which plans need to be modified moving forward.

In Debra Johnson, the RTD board has recruited a leader with the resume and experience needed to improve operations, strengthen governance, and define a post-FasTracks future for RTD. Now the agency just needs to listen to her.

New TransitCenter Report: To Solve Workforce Challenges Once and For All, Transit Agencies Must Put People First

New TransitCenter Report: To Solve Workforce Challenges Once and For All, Transit Agencies Must Put People First

TransitCenter’s new report, “People First” examines the current challenges facing public sector human resources that limit hiring and retention, and outlines potential solutions to rethink this critical agency function.

Read More “Who Rules Transit?” Chronicles the Gulf Between “Who Decides” and “Who Rides” at Transit Agencies

“Who Rules Transit?” Chronicles the Gulf Between “Who Decides” and “Who Rides” at Transit Agencies

Our latest report reveals a yawning gap between the demographics of transit riders – primarily women and people of color – and leadership at transit agencies – primarily white men.

Read More