During the protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism sweeping the nation, transit agencies in numerous cities decided to curtail and suspend transit service. In most cases, transit riders were given little, if any, advance notice, and many were left stranded. At the same time, police departments commandeered buses to transport officers as well as protesters who had been arrested.

These decisions were made with little regard for the material consequences they imposed on transit-dependent riders, and are emblematic of the vast disconnect between transit agency leadership and the riders they serve.

In Cincinnati, SORTA suspended all transit service at 9 pm on the evenings of May 31 and June 1 in response to protests downtown. Rather than rerouting buses around streets disrupted by protest, Mayor John Cranley “took a reactionary approach and leapt immediately into shutdown mode,” according to local transit advocate Cam Hardy. Riders left stranded then watched in dismay as buses were commandeered to transport people who had been arrested for protesting.

I’m livid. People were stranded

last night. Buses stopped running at 9pm. I was willing to accept that for the sake of operators safety. But then @KregKeesee comes up with an idea to hand our bus system off to the cops and force supervisors to drive the buses! INSANE.

— Cam 🚍🚍 (@camhardy513) June 1, 2020

In Miami, Mayor Carlos Gimenez ordered the suspension of transit service from Saturday evening until early Monday morning. This left Miami transit riders, the majority of whom are Black or Latino, without transportation options.

Local advocates were incensed. “A complete system shutdown deepens the racial and economic inequities that have contributed to the unjust reality that Black and brown communities face today, by further isolating them from their fellow citizens and making their lives during this incredibly challenging time even harder,” wrote Transit Alliance Miami in an open letter to the agency’s leadership.

In Los Angeles, Metro suspended service in downtown Los Angeles in the afternoon of May 30, a Saturday. The agency then expanded the shutdown to the entire system shortly after the city’s 8 pm curfew. Riders received less than an hour notice that the shutdown was coming. In LA, 52% of riders make $20,000 a year or less, and 23% make less than $5,000. Taking a taxi is simply not an option for these riders. In an apology letter, LA Metro explained that it made the decision to “protect transit riders and operators.” But advocates quickly pointed out that by subsequently allowing buses and union bus drivers to be used to transport police, LA Metro made a mockery of the idea that the decision to suspend service was to protect operators.

These are some of the most egregious examples of abrupt service cancellation, but transit riders in San Francisco, Boston, Washington DC, and Chicago also had to contend with station closures and service changes marked by minimal communication.

These sudden shutdowns are most harmful to low-income people and people of color. Nationally, 36% of transit riders are essential workers, who political leaders have recently lauded as heroes. Essential workers are more likely to commute outside the typical rush hour, with 41 percent working shifts outside the 9 to 5 workday. In American cities, people of color account for a disproportionate share of the 2.8 million essential workers who usually commute on transit. Cutting off the service they rely on is no way to honor the contributions they make towards keeping our cities running.

Protesters exercising their first amendment rights were also harmed by these decisions. Cutting off transit service amidst the protests made it more likely that they wouldn’t make it home before city-mandated curfews, putting them at risk for arrest and wanton brutality from the police.

Decisions about service provision during unpredictable disruptions are not simple or easy. Agencies have a responsibility to keep riders and transit workers safe, and it’s understandable that transit managers would be concerned about steering transit vehicles full of passengers near phalanxes of armed police and highly-charged protests. But the goal of transit is to give people access — that can mean access to their jobs or access to their rights to speech and assembly — and in these instances transit became a tool of exclusion. Transit agencies should strive to provide freedom of movement, even in challenging conditions.

During the protests, pushback from transit unions and rider advocates quickly compelled some agencies to revise their policies for cooperating with police. Unionized transit operators across the country overwhelmingly rejected requests to transport detainees and police officers. Advocates in Boston and some MBTA board members prevailed on agency leadership to stop driving police to and from protests.

Going forward, agencies should revisit the protocols that allow their services to be used to transport police or detainees. In Los Angeles, LA Metro said the agency had no choice but to transport police because of a law that requires mutual aid during times of emergency. Those arrangements should be revised in recognition of the role that police play in perpetuating racism and violence against people of color, who are the majority of transit riders.

It’s also essential for agencies to publicly post their emergency management plans, and to ask for input from riders when developing those plans. In Boston, TransitMatters has asked the MBTA to commit to remaining operational during times of protest, and to create a plan for emergencies that prioritizes riders: “The bar for closures related to safety needs to be high, proper communication and transparency in decision making must be ensured, and the MBTA must always find a way to safely transport riders as soon as it is safe to do so.”

Agencies should commit to localized service suspensions instead of blanket shutdowns. Rerouting buses around protest sites makes sense, shutting down entire systems does not. As former Houston Metro board member (and current TransitCenter board member) Christof Spieler tweeted on Sunday, “It’s OK to tell people to walk a few blocks to a bus. It’s OK to feed buses into the subway. It’s OK to adapt on the fly, and to coordinate with the city to keep things safe. But just leaving people to walk 10 miles home is not OK.”

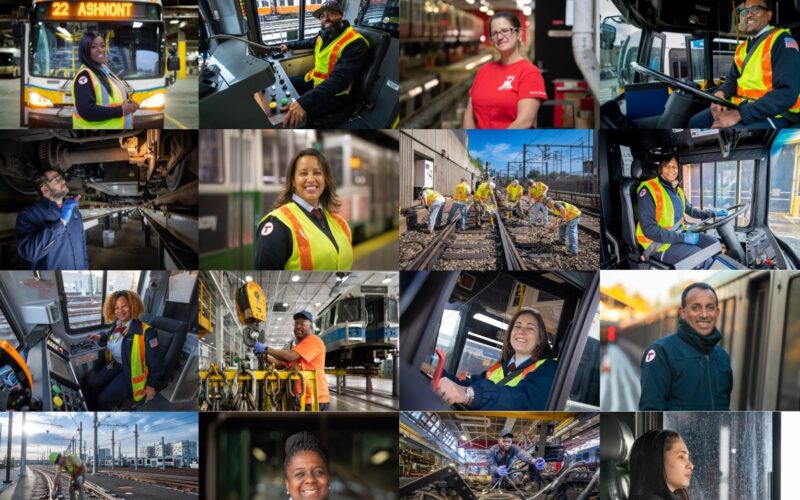

In the longer term, transit agencies must make changes at the leadership level to become more representative of riders. As we’ve chronicled extensively, transit agency board members and executive leadership are generally much richer and whiter than the average transit rider. Insulated from financial constraints, they can cancel service and expect that everyone will just take an Uber instead. Most transit agency board members do not ride the systems they oversee, and have no idea what it would be like to have to walk home in the middle of the night after working a 12-hour shift.

Groups like Tri-State Transportation Campaign in New Jersey and OPAL in Portland have organized successful campaigns to appoint board members who ride transit, and CEOs who reflect the transit-riding community. To effect real change, a larger number of advocacy groups will need to take on this work. While representation is not a cure-all, it’s likely that service decisions in response to civil unrest would have been different if agencies were more reflective of the people they serve. Transit riders need to demand a place in the room where decisions are being made. The stakes are clearer than ever.

On Track for Success: Decoding Montreal’s REM Model for Efficient Transit Projects in the U.S

On Track for Success: Decoding Montreal’s REM Model for Efficient Transit Projects in the U.S

Why is it so difficult to build subway and light rail projects in America? Every week there’s a new story about an American transit project that is behind schedule, over budget, or “paused”. Montreal’s Réseau express métropolitain (REM) stands out as a recent North American project that has begun to address some of the challenges that have foiled so many others. What is REM getting right that other projects aren’t?

Read More MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and its union, Carmen’s Local 589, reached a historic agreement to increase bus operators' starting wages from $22.21 to $30 an hour, shifting MBTA operators from the lowest paid to the highest paid in the transportation industry.

Read More