Christof Spieler is the author of Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of US Transit. He serves on the board of trustees of TransitCenter and formerly served on the board of directors of Houston METRO. In Houston, he was instrumental in a redesign of the agency’s bus network that has led to increased ridership, bucking national trends. With the MTA embarking on a redesign of New York City’s bus network, we’re pleased to present this post from Christof evaluating the agency’s draft network redesign for the Bronx.

More people rely on the bus in the Bronx, per capita, than in any other borough. Yet too many Bronx bus riders deal with long waits, slow trips, and roundabout connections, as Stephanie Burgos-Veras of Riders Alliance told the audience at a recent TransitCenter event. It shows: Bus ridership in the Bronx — where 60% of households do not own a car — dropped 16% between 2016 and 2018.

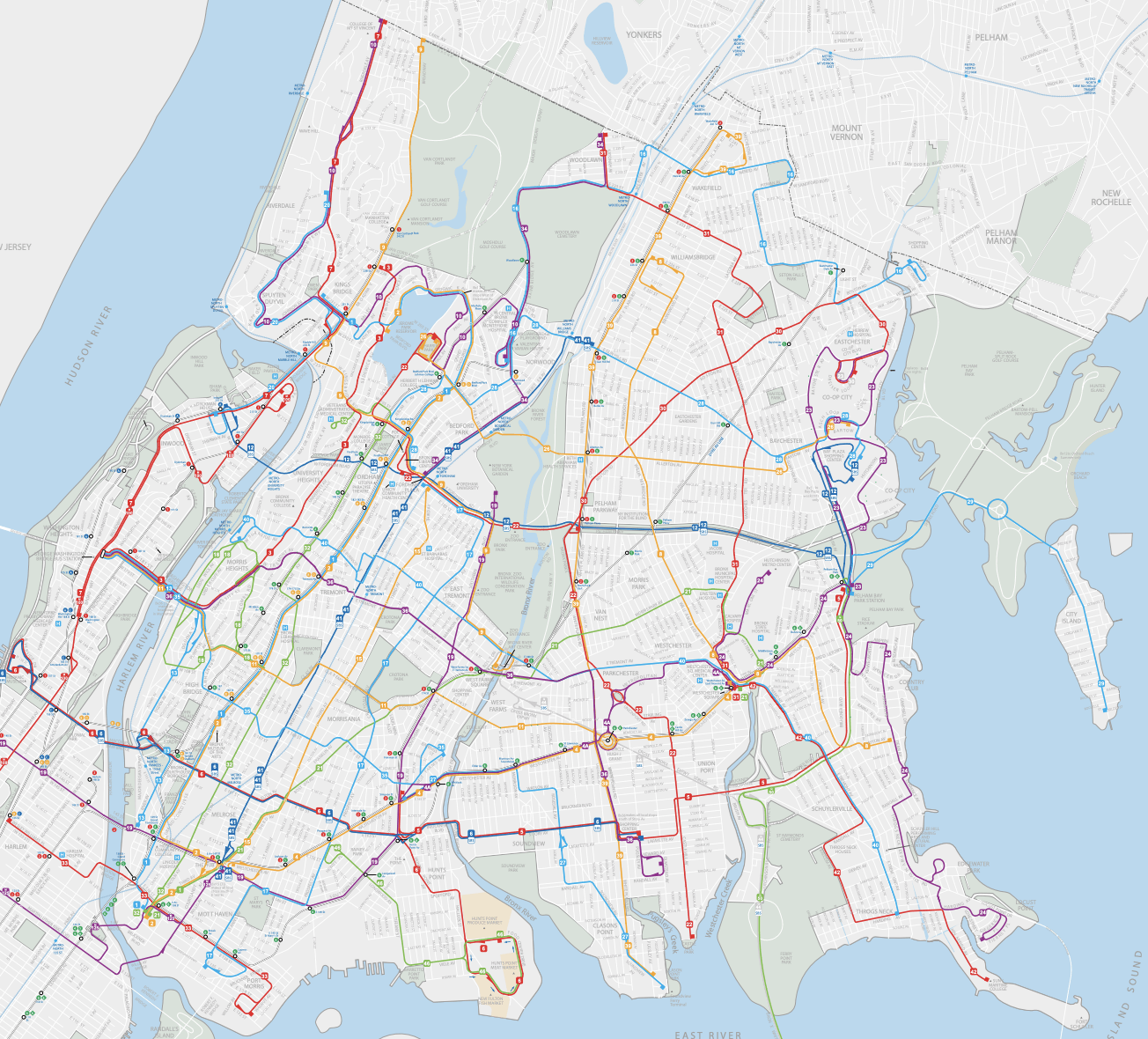

In June, the MTA released a draft plan to redesign the Bronx bus network. There’s no doubt that the proposals will improve trips for bus riders. Among other changes, the plan eliminates time-consuming turns along the Bx36, simplifies the tangle of routes around Co-op City, and creates better spacing between stops so buses spend less time standing still.

But given the gap between the current state of Bronx bus service and what Bronx bus service can be, is this plan as ambitious as it should be? Will it do enough to get bus riders where they want to go quickly and reliably?

In Houston, we concluded that we couldn’t achieve what we wanted without changing everything. A “blank sheet” approach meant every route — even the successful, high ridership ones — was up for grabs. The planning team based the new network largely on street segments that already had service, and provided frequent service on streets that already had high ridership, but connected those segments in new ways.

In the Bronx, the MTA seems to have taken the existing network as a starting point and made changes where deemed necessary. That’s how the plan is presented — a series of adjustments to the existing routes. As a result, the draft plan leaves too many oddities and inefficiencies in place. The Bronx may not need a full-on “blank sheet” redesign like Houston did, but it looks to me like it will take bigger changes to give Bronx bus riders the service they deserve.

Every redesign needs to be judged on how it improves service for riders. There are five main ways that network redesigns can do this. Looking at the Bronx plan through this lens will help us evaluate it.

- Frequency. A good redesign can improve frequency by simplifying the network. When multiple routes run on the same street, there may be six buses an hour, but with uncoordinated schedules that could mean 20 minute gaps between buses, followed by several buses right after each other.

- Connectivity. A redesign can create better connections to more places. That can mean extending the bus route that runs through your neighborhood, or it can mean that route now connects to more routes. In an ideal grid network, every destination is no more than one transfer away.

- Travel time. One way to make trips faster is to straighten out routes that go a few blocks out of the way to serve a particular destination. Another is to set up connections in convenient places, so a rider doesn’t have to ride out of the way to get to the transfer point.

- Reliability. A route with fewer turns — especially left turns, which require more merging and waiting for gaps in oncoming traffic — is less likely to have delays. A network that is less dependent on transfers at a few congested hubs will also have fewer delays.

- Legibility. A good transit network is easy to understand. That’s essential for new riders but also for people who depend on transit for all their trips and thus make trips to a variety of places, not just the same daily commute.

Fundamentally, redesigns achieve these improvements by simplifying a network. The complexity of most bus networks leads directly to lower frequency, poor connectivity, unreliable service, and of course illegibility. Redesigned networks will generally have fewer routes, and those routes will be relatively straight and direct.

There are many ways to evaluate a transit network: We can look at travel times between major destinations, we can measure how many people are served by frequent service, and we can quantify increases in midday, weekend and evening service. But one of the most basic ways to consider a network is to look at the map and see how simple it is.

So how does the proposed Bronx network look? When I look at the map I immediately see complexity.

In the northwest Bronx and along the Grand Concourse, for example, you can see duplicative service — holdovers from the old network that limit frequency and connectivity in the new network. At its northern end, the 7 first duplicates the 10 (which then goes on to do the same things as the 20) and then the 20 and the M100:

Click to enlarge

The 7, 10, and M100 all run every 10 minutes or better. If there was only one route on those duplicated segments the remaining service could be even more frequent, and transfers would be very easy. The 20 is peak-only; every trip made on that route could be made with a single transfer. This duplication is adding complexity with little obvious benefit to riders.

The 7, 10, and 20 also connect to the 1 along the Grand Concourse – a high ridership corridor despite the subway lines below. In addition to the subway, the Grand Concourse is served by duplicate bus routes – the 2 does nearly exactly the same thing the 1 does, but is different at both ends. A single route combining the two would be easier to understand and use.

There are similar things happening for crosstown service in the southern Bronx. Today, the 4 and 4A are two variants of the same route, overlapping most of the way to increase service frequency and taking different routes on the north end. The plan shortens the 4A, leaving only the 4 covering the southernmost part of the route, and increases frequency on both. This reduces duplication, which is good.

Click to enlarge

If we look at the larger plan, though, it seems like there are opportunities to improve service here by integrating the 4A with other routes. The 35, for example, ends halfway across the Bronx, missing a key subway connection and connections to other bus routes. The 4A and 35 could be merged into a single route. Further north, the 11 similarly stops short; it could take over the northern bit of the 4A, the only part that doesn’t duplicate the 4. In that way, it could offer residents who live along the 11 connections that they don’t have today.

In following the pattern of the existing routes, the new network misses opportunities to better connect the different parts of the borough. The Bronx is well-served by a series of north-south subway lines:

Click to enlarge

If you’re headed to Manhattan, the subway is the best way to get there, and many Bronx residents are within walking distance of the subway. Thus, in an integrated network, the buses serve two roles: getting people in neighborhoods not served by the subway to the subway, and serving trips that aren’t going to Manhattan.

Now look at Hunts Point, a significant employment center with nearly 20,000 jobs in the wholesale market and surrounding businesses. In the redesigned network, it’s served by two routes (the red ones in the map below). The 46 runs every 30 minutes; it serves some lower density neighborhoods. The 6 is the key route; it will run every 8 minutes. It’s a really useful connection intersecting all of the subway lines that serve the Bronx (thick blue lines) and multiple north-south buses (thin blue lines):

Click to enlarge

Just as in the current network, though, there’s no north-south route to Hunts Point. That means the majority of bus routes in the Bronx (gray lines) require two transfers to get there. Hunts Point has a good subway feeder, but not good connections to the rest of the bus network. That means, ironically, that it’s easier to get there from Manhattan than from most of the Bronx.

In some cases, optimizing the bus network will require changes to street layout or physical infrastructure that involve teaming up with NYC DOT. Fortunately, the roll-out of bus lanes and transit signal priority have already set a precedent for this coordination.

The M125, for example, takes different paths northbound and southbound to get from Manhattan to the Bronx. As a result, the northbound bus misses a subway station (though it connects to another station on the same line) and several bus routes. This happens because the Third Avenue Bridge and the Willis Avenue Bridge are both one way. That’s not a simple thing to change, but with support from the mayor and coordination with NYC DOT, a contraflow bus lane could solve this.

Click to enlarge

I’ll freely admit that I’m not an expert on the Bronx, and things that look illogical to me may in fact be the best solution. The MTA has good transit planners, and they know what they’re doing. Each of their network decisions reflects a current connection that draws riders, an optimization to save service hours, an awareness of political limitations.

But it’s also clear to me that New York’s bus service (like the bus service everywhere else in the United States) fall far short of what bus service can be, and if New York wants to provide bus riders with excellent service, it will take ambitious changes. This plan doesn’t look ambitious enough to me.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Thanks to Riders' Alliance successful #6MinuteService campaign, New York City subway riders will enjoy more frequent service on nights and weekends, starting this summer. In this post, we chronicle the group's winning strategies and tactics.

Read More