Since 1980, residents of Los Angeles have voted four times to tax themselves to fund transportation projects, including rail lines that were supposed to transform LA into America’s next great transit city. But speculation about the impending liberation of LA from car dependence and congestion is premature, to say the least.

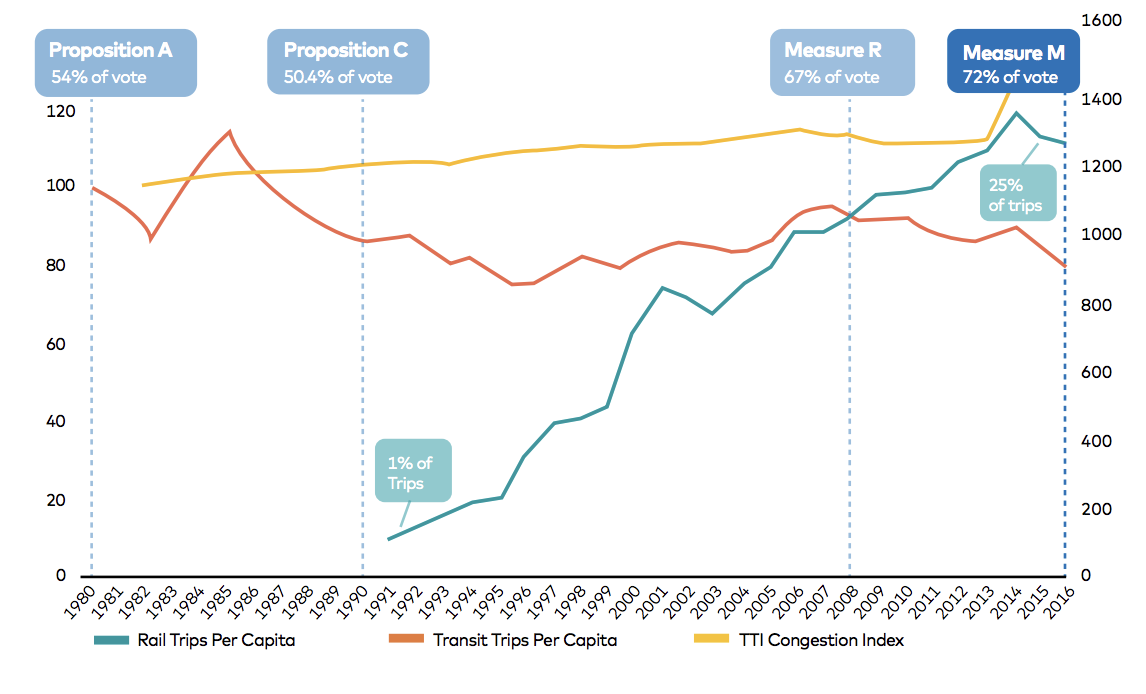

Transit ridership in Los Angeles today is lower than it was 40 years ago, and driving remains the mode of choice for the vast majority of trips. If Los Angeles is going to capitalize on the $50 billion slated for transit expansion over the next 40 years, thanks to the passage of Measure R in 2008 and Measure M in 2016, officials will have to change course.

In a new research paper, summarized in this TransitCenter brief, UCLA professor Michael Manville examines why LA’s earlier transit investments failed to deliver, and why its next round of projects must be accompanied by a thorough overhaul of street-level transportation and development policy. It’s a must-read for policy makers and advocates in Los Angeles, not to mention other cities looking to translate victory for transit funding at the ballot box into better transit service that will benefit and attract riders.

Victory on election day is just the beginning

Getting the votes to put transit funding over the top is the easy part. Implementing the full suite of policies to make transit succeed is harder.

Like most American cities, Los Angeles wasn’t built for transit riders. Streets are wide and hostile for people walking to transit stops. With no substantial network of transit-only lanes, bus riders are left to stew in the city’s car congestion. Even major investments in rail like the Expo and Blue lines slow to a crawl downtown because streets have not been engineered to prioritize transit instead of cars. The region is also awash in free parking and low-density development that spreads destinations farther apart, disadvantaging transit in relation to driving.

These problems are fixable if political leaders sustain attention to them beyond election day. Street space has to be repurposed to give buses and trains dedicated rights-of-way that won’t get clogged with cars. Development rules have to be rewritten to reduce parking mandates and enable the kind of walkable development that enables transit to flourish in cities like New York and Boston. Seattle followed up victorious transit ballot measures by running more frequent bus service, adding bus lanes, and redesigning streets to be safer for walking — it’s now one of the rare American cities where transit is on the rise.

Rethinking the place of the car on our streets makes for tough politics. Los Angeles voters are more likely to approve of transit in the abstract than to support these concrete pro-transit policies, according to Manville’s surveys. But that’s no excuse for inaction. It’s a wake-up call for public officials: Victory on election day is just the beginning, and billions for transit will be wasted if they don’t follow through on complementary policy reforms.

Transit that wins votes is no substitute for transit that wins over riders

Focused on accumulating votes, LA’s transit campaigns tended to lose sight of the imperative to design and build transit that works for riders.

The core constituencies riding transit in Los Angeles are primarily low-income residents, including many immigrants. The surest way to increase transit ridership would be to upgrade service on the corridors where people are already riding in substantial numbers, improving the experience for existing riders while pulling in new riders where the market for transit is strong.

But instead of appealing to these riders, many LA transit projects continue to be based on political geography and poll-tested appeal to other voting blocs. The region has built rail lines to suburbs and wealthy communities where there is little potential for ridership (at least without significant new development) rather than improving service for existing transit riders. One consequence is that, while some transit ridership has shifted from bus to rail, total ridership per capita has stagnated for decades.

Transit ridership in LA, 1980-2016, “Voting Is the Easy Part,” p. 4, Manville et al, 2018

Some compromises to win votes may be necessary, but if the end result is a transit expansion plan that doesn’t increase transit ridership, those tradeoffs aren’t worth whatever may be gained in return.

Developing a transit plan that works as politics and as policy

Cities aren’t doomed to weaken their transit plans in the quest for votes. It’s possible to craft a project list based on sound transit policy that wins on election day.

One of Manville’s findings suggests that in blue cities (i.e. most urban areas), partisanship can help carry effective transit projects to victory. In LA, identifying as a Democrat was a stronger predictor of supporting Measure M than location or experience riding transit. If partisan identity motivates voters to support transit ballot measures more than the proximity of proposed transit lines to one’s home or workplace, policy makers may have more leeway to avoid compromising their project lists than they imagined — especially in presidential election years, when Democratic turnout is highest. Democrats will support transit because that’s what Democrats do, not because they will benefit personally.

Voters can also be moved by considerations beyond self-interest or partisan affiliation. In Indianapolis, hardly a bastion of left wing political identity, residents voted in 2016 to raise the city’s income tax to expand bus service. Advocates argued that better transit would connect poorer residents to jobs, groceries, and healthcare. Ridership is up 3.4% since the changes were implemented last February.

Different messages may resonate in different cities — advocates should conduct local opinion polling to hone their pitch. But always keep in mind that it’s better to refine a message in support of good transit policy than to water down transit policy in search of a winning message.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

To create the “state-of-the-art bus transit system” of his campaign platform, Mayor Adams will have to both expand the quantity and improve the quality of bus lanes. We recommend these strategies to get it done.

Read More