Growing up at the northern fringes of the Boston Metropolitan Area, my family would drive the 30 miles into Boston for various events, be they cultural, culinary, or other. The drive into the city was always the same: breeze over the NH-MA boarder, down Interstate 93, and make our way to Boston, but before crossing the Charles River to the city, we would meet “The Bridge.”

This bridge was more of a dysfunctional combination of rusted, elevated highways and abandoned exit ramps that would literally dead end at a precipice. On top of that, this “designed” system was being overhauled by the most expensive transportation investment in the United States: The Central Artery Tunnel Project or what everyone begrudgingly called The Big Dig. This project’s planning process started the year I was born and didn’t finish until two years after I had graduated from college in 2005. I know that it takes long time for transportation capital projects to finish, but 25 years?

After billions of dollars of cost overruns, ten years of delay, many design flaws, some criminal arrests, and the loss of a life, the Big Dig has relieved some of the congestion, but mostly just put it out of sight in a large tunnel system. There is an easier connection to the airport and and reconnected the North End to the rest of the city with the Rose Kennedy Greenway. Yet, to me, getting into Boston is still a pain by car.

In the wake of the $15 billion Big Dig, the Commonwealth is trying to steer transportation investment in a more efficient and productive manner. Last week, TransitCenter staff had the chance to attend an event in Bean Town organized by Transportation for Massachusetts and Transportation for America called “Measuring Up: More Bang For The Buck in Transportation Project Selection.”

Here’s a novel idea: have criteria to rate projects to figure out which would be the best in your region!

Easier said than done, but the idea is that more and more money for transportation projects is not necessarily the correct way to move forward. The money needs to be backed up with quantifiable public benefits that rationalize expenditures.

Steve Heminger, who is the Executive Director of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission in the San Francisco Bay Area dug deep into the situation for his region of nearly 8 million people. To give some perspective on funding for MPO’s, he showed a chart of the 20 largest MPOs displaying the percentage of the budget devoted to operation and maintenance costs versus money for expansion. The top five all had more than 90% of the budget devoted to operation and maintenance. Contrast that with the smaller cities, with new transportation infrastructure that had more money devoted to expansion. For those cities with existing, robust transportation networks, the tiny sliver of the pie that is used to expand has to be heavily scrutinized. Since there is not a lot of money in the pot, governments must spend it wisely.

Therefore, SFMTC has a detailed process for choosing transportation projects based on cost, impact, and most importantly, performance measures. The introduction of a formalized process to select the most effective transportation project is beneficial and individual project evaluation allows for greater transparency and accountability. All of this seems like a great way to pick transportation projects, in theory.

Here lies the problem: there are certain biases that the creators of the criteria have which will benefit certain projects over others. Hopefully the criteria will have a bias towards good transportation projects, but this “good” is subjective. Even Hemminger is aware of this fact and the measurements that an agency chooses will dictate what projects will be selected.

How do we ensure that the criteria used to measure transportation projects are reliable and appropriate? To start with, it seems like this task should be the job of transportation planners. Isn’t this what they are trained for? I understand that the transportation world is changing, since a system of project review in the 1950s would skew towards highway construction, but an accepted vision today is beginning to emerge. Cities need to provide more options to have multimodal choices for mobility. In tandem with this criteria and project selection, there should be a robust monitor and evaluation program, which will then feed back into the criteria. This constant iterative process will enhance and improve the program.

This is delicate territory for the transportation world and I certainly commend a fresh look at appropriating money for better transportation projects so we don’t have more Big Digs on our hands. Projects like the Green Line Extension are coming to the region, which will provide rapid transit access to Somerville, the densest place in New England for one tenth of the cost.

It makes sense that governments should be putting transportation projects through a rigorous review. No individual would buy something today without some research beforehand. If we can continue to improve the process of project selection with performance measures, everyone benefits. I hope that some day there will be more options for me to make the trip down from New Hampshire to Boston instead of getting stuck in a traffic jam, but what would Boston be without its infamous driving experience? Probably a better place!

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

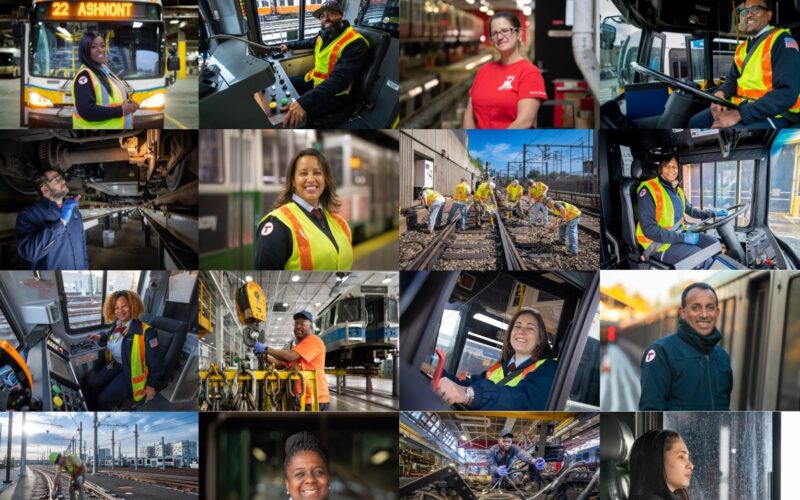

MBTA Partners with Union to Reach Historic Wage Agreement

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and its union, Carmen’s Local 589, reached a historic agreement to increase bus operators' starting wages from $22.21 to $30 an hour, shifting MBTA operators from the lowest paid to the highest paid in the transportation industry.

Read More