Los Angeles Traffic by Luke Jones is licensed under CC by 2.0

“In India “smart” cities initiatives are those that help cities do more with less—not necessarily anything to do with technology.”

Om Agarwal, Indian School of Business, presenting at the Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting

Today’s conversation about “smart cities” is driven by buzzwords like ‘big data’ and ‘internet of things’ that veil how vague their promises are. Whether it’s the chatter around driverless cars or the seduction of emerging mobility partnerships, too often cities view technology as a starting point rather than one of a possible range of solutions, and they are heavily abetted by the transportation tech lobby. Take this recent blog post by Lyft co-founders John Zimmer and Logan Green. How should cities use technology to address age-old urban problems like traffic? Their answer turns out to be congestion pricing, or at least tolled lanes.

More widespread application of congestion pricing would be terrific. But the barrier to congestion pricing is political, not technological. London introduced its congestion charge in 2003, several years before anyone had heard the term “iPhone.” It has been in place in Singapore for far longer.

The path to smarter cities typically has less to do with technology and more to do with better planning and policies. Rather than proposing solutions in search of problems, cities should ask themselves tough questions such as; what will make our city a place people want to be, and a place where business will invest? If congestion is a problem, how should we allocate road space across transportation modes? How can we promote choices like biking, walking and transit? What are our biggest challenges and inefficiencies, and can new data and technology realistically help address them?

In instances where technology can contribute, cities should set clear goals and use data to evaluate programs, management and decision-making, not become distracted or check a box regarding a shiny new thing.

Misplaced priorities

Recent federal programs have encouraged cities to seek technological solutions, which has resulted in widespread interest in forming public-private partnerships with TNCs. However, no transit agencies or cities partnering with TNCs have successfully negotiated data access necessary to evaluate the efficacy of the partnership.

For example, in Private Mobility, Public Interest, we analyze Boston’s 2015 data-sharing agreement with Uber, the core failure of which was that the agreement did not yield data that the City either wanted or could share with other agencies. Rather than the standard origin destination information required of taxis in, say, New York City, the data about pick ups and drop offs to the City of Boston was provided in zip code format and wasn’t helpful for planning.

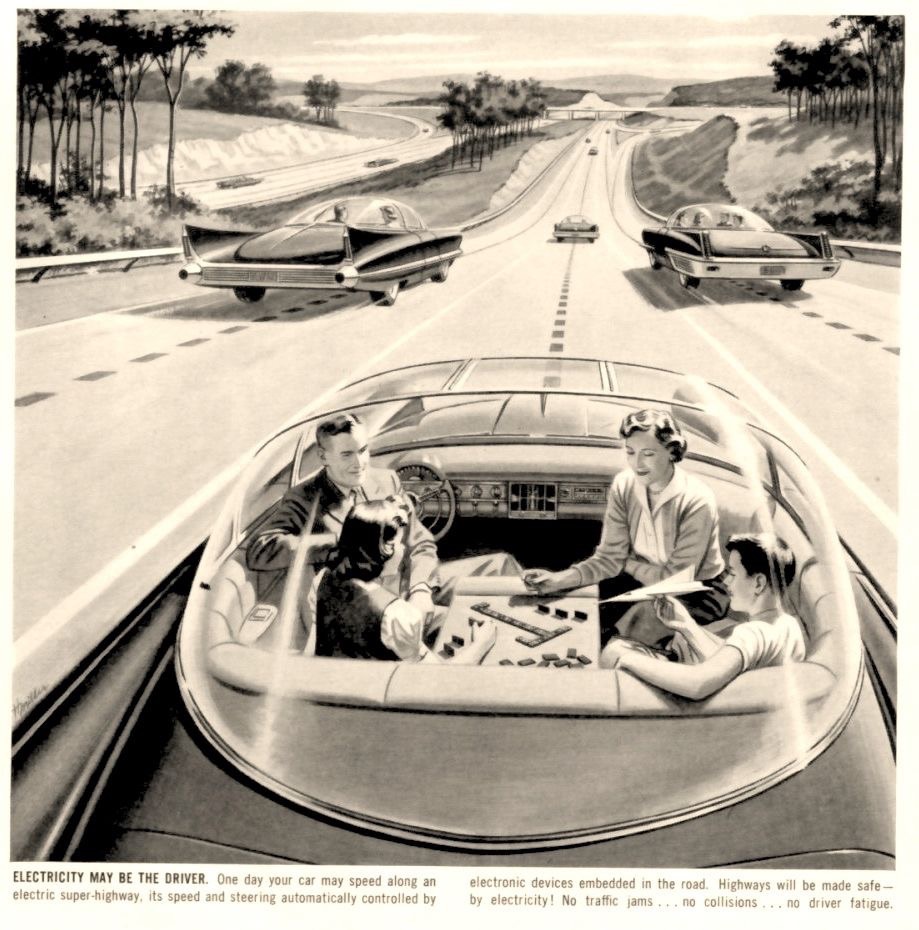

Driverless cars, which do not yet exist, are in a class of distraction all their own. The City of Madison is a partner in one of ten USDOT-designated “proving ground” driverless car testing projects. Madison will be pursuing several driverless vehicle pilot projects — one at the University of Wisconsin, one on a private company’s campus, and another at a dedicated vehicle testing site. City leaders must remember that tests of future technology with no clear adoption timeline do nothing for citizens today, and in any case, technology that works will be adopted broadly, not just where it has been tested.

The future will have board games

A more enlightened path

Madison need not look beyond its own backyard to see how data and technology can make an immediate impact. The University of Wisconsin-based State Smart Transportation Initiative (SSTI) is working with government partners in California to respond to a longstanding transportation need by adopting new tools. They’ll be wrapping up a TransitCenter-funded project this summer using big data from cell phones and GPS units to analyze opportunities to improve walking and biking facilities around light rail stations in the Sacramento area.

Columbus, OH, is becoming a case study in how to take a holistic approach to data- and technology-augmented management. The city won USDOT’s Smart City Challenge in 2016 for good reason – their application connected the city’s overall goal of improving mobility to several real world solutions. In addition to exploring possible technological fixes like smart sensors that collect data on traffic patterns, the Central Ohio Transit Authority is also redesigning its bus network to better meet the needs of today’s citizens and businesses. Columbus is also pursuing ‘smart’ opportunities across sectors, not just in transportation.

Many cities in the midst of changing their approaches to transportation have forging ahead without the “smart city” moniker attached. New York and Chicago have been demonstrating leadership in recent years by boldly reallocating street space for uses other than private vehicles. Both have faced the accompanying political battles head-on rather than using technology as an evasion.

Chicago’s Smart Loop Link

What actually makes a city smart? Safe streets that enable people to access destinations they care about quickly, via a menu of transportation options that can accommodate different people and different kinds of trips. As Tom Wright, head of New York’s Regional Plan Association, recently told the audience at a “City of Tomorrow” event, “a smart city is made so not by a technology, but rather a commitment to trying things out, which encourages citizens to begin to see urban space as mutable and something they can influence.”

Cities won’t get smarter simply by using new data and technology. But in the context of goal-setting and commitment to innovation and problem-solving, they can use technology to do more.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

A Bus Agenda for New York City Mayor Eric Adams

To create the “state-of-the-art bus transit system” of his campaign platform, Mayor Adams will have to both expand the quantity and improve the quality of bus lanes. We recommend these strategies to get it done.

Read More