Our latest Ridership Initiative guest post comes to us from Transportation at McGill Research (TRAM) group members Geneviève Boisjoly, Emily Grisé and Ahmed El-Geneidy—researchers who have taken a deeper dive into the National Transit Database than you will hopefully ever need to. If you, your research group, or your transit agency would like to share your story or hear from someone else about a particular topic, let us know by emailing [email protected]

Public transit ridership had been steadily increasing since the early 2000s in urban areas across North America before a more recent decline, nearly across the board, since 2014. This ridership decline has caused agencies to investigate the factors that might be contributing to public transit ridership changes in North American regions.

To better understand the key levers for maintaining or increasing public transit ridership, our research team collected and analyzed publicly available data on public transit usage and operations between 2002 to 2015 for 25 large transit authorities operating bus and rail services in North America. While many factors influence transit ridership, our study’s longitudinal multilevel regression analyses highlight one in particular as the most important: cities must properly fund their public transit operations, especially bus services, to ensure a steady increase in ridership.

Invest in the ride

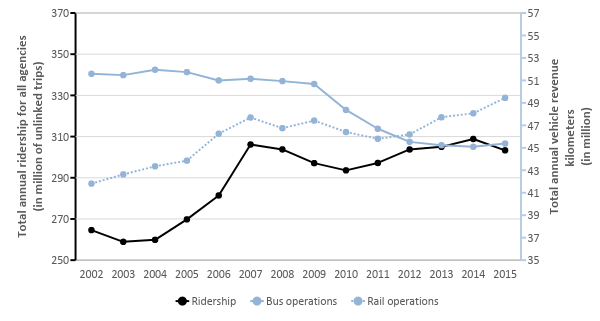

The volume of service delivered by a transit agency in a region is by far the largest factor explaining public transit ridership in the North American metropolitan regions we studied. The more service a transit authority provides (measured as the number of kilometers driven annually by public transit vehicles—VRK), the more transit trips it will attract. As shown in the figure below, increased rail VRK from 2002 to 2007, together with relatively stable bus VRK, is associated with increased ridership. A similar increase in rail operations from 2011 to 2015 did not yield the same consistent ridership increase, perhaps due to the simultaneous decrease in bus operations. These observations suggest that increasing rail service is insufficient to increase ridership, particularly if bus ridership is not preserved.

Total US ridership and operations (vehicle revenue kilometers – VRK) per year. Note that the data from the Canadian agencies is not included in this graph, as mode-specific data was not available consistently for this time period.

Our model also shows a much stronger relationship between bus service volume and ridership than rail service volume and ridership. While further research is needed to explain this effect, we can propose some hypotheses. First, rail systems typically do not provide comprehensive service coverage in North American cities, instead serving mainly central areas and suburban commuting trips. As a result, a large share of the population depends on buses for their daily trips. In cases where the bus network has been partially designed to complement the rail network, reduced bus operations might include reductions in service frequency and coverage of bus feeder services, which would in turn also negatively impact the use of rail service.

Stop blaming others

Many external factors have been suggested to contribute to transit ridership declines, including reduced gas prices and increased use of Uber or bike-sharing systems, for example. While gas price has a statistically significant influence on transit ridership, its impact is much weaker than the internal factors that transit agencies and municipalities control, such as vehicle operations (VRK) and transit fare. The presence of Uber and bike-sharing systems in a given metropolitan area does not have a statistically significant impact on transit ridership in this study, although we did not have access to data on for-hire vehicle or bikeshare trip volumes. Nonetheless, these results suggest that the North American transit ridership decline cannot be explained merely by gas price fluctuations or the emergence of new mobility services—instead, it is best explained by declining bus services.

This macro-level analysis has some limitations. Firstly, the selection of variables is limited by the data that is available and consistent across all agencies. Accordingly, we used simplified and aggregated data as proxies for some complex variables, which do not fully reflect reality. For example, the mere presence of Uber or bike-sharing in a city (rather than more detailed data, like the number of trips) is likely not sufficient to assess the degree to which emerging mobility services impact transit ridership. Secondly, such an analysis does not take into account local particularities in transit networks, street design, or other demographic contexts that might also explain changes in ridership. Macro-level analysis is nonetheless essential to understand broad urban transit trends, and can be used to inform the design of local, spatially-explicit analyses.

In search of new revenues

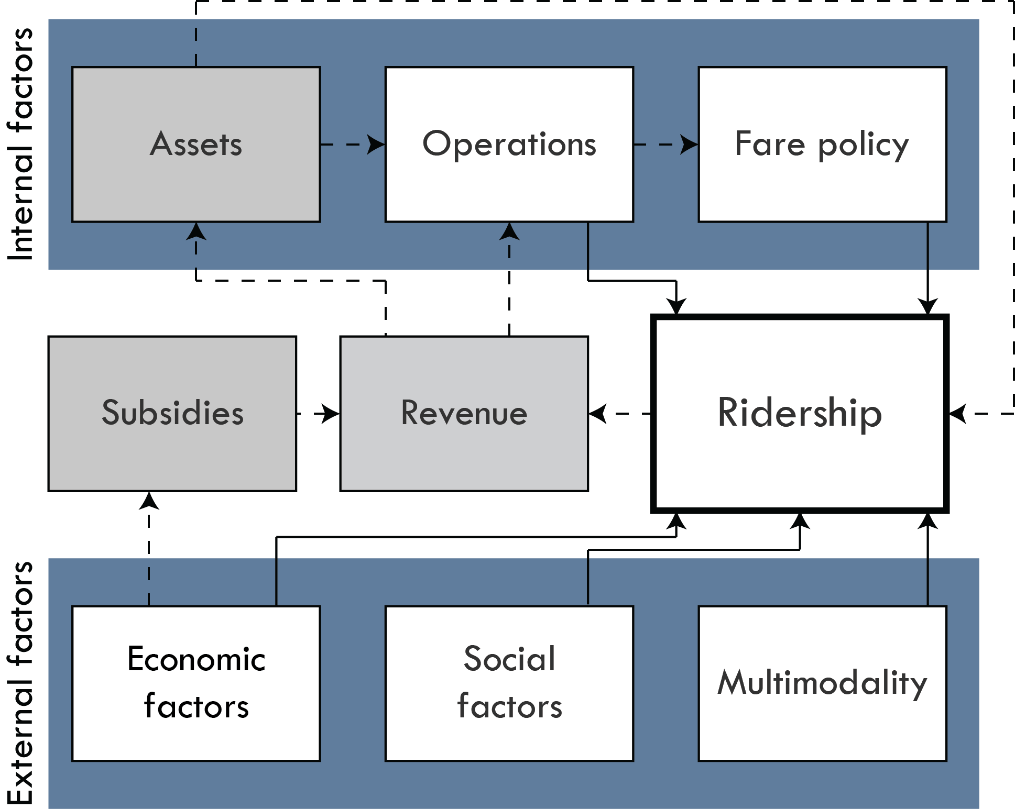

Our research suggests that continued investment in transit operations, both rail and buses, is essential to mitigate the transit ridership decline in North American cities. As illustrated in the figure below, transit agency revenues influence the amount of investment that can be made in assets and operations. Revenues come from a combination of sources, including government tax, fare, and advertising revenues. Transit fares—perhaps the easiest source to grow—also strongly impact ridership (higher fares lead to fewer riders), as our study and others have shown. With that trade-off in mind, additional revenue sources are inevitably required to support greater investments in transit operations.

On the one hand, policy-makers and planners need to explore more sustainable local funding sources for public transit, such as transit funding ballot measures, congestion and parking pricing, and land value capture initiatives. On the other hand, transit agencies are typically unprofitable by design, so it is important to cultivate political and/or public support for transit subsidies as an investment in the community. Finally, cities and transit agencies must think critically and strategically about how to increase operational efficiency through transit priority measures like dedicated bus lanes or all-door boarding. These operational strategies can enable operational time savings that agencies can reinvest to increase service frequency and coverage, the essential ingredients in growing transit ridership.

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

On the Brink: Will WMATA’s Progress Be Erased by 2024?

The experience of being a WMATA rider has substantially improved over the last 18 months, thanks to changes the agency has made like adding off-peak service and simplifying fares. Things are about to get even better with the launch of all-door boarding later this fall, overnight bus service on some lines starting in December, and an ambitious plan to redesign the Metrobus network. But all of this could go away by July 1, 2024.

Read More Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Built to Win: Riders Alliance Campaign Secures Funding for More Frequent Subway Service

Thanks to Riders' Alliance successful #6MinuteService campaign, New York City subway riders will enjoy more frequent service on nights and weekends, starting this summer. In this post, we chronicle the group's winning strategies and tactics.

Read More